After sermons, unsafe abortion kills

It is a sunny Saturday when thousands gather at Iyegha near Karonga Town. The opening of St Joseph the Worker Cathedral of the Diocese of Karonga is underway.

Sermons. Songs. Dances. Ululations. This is no day of small things. Pope Francis was invited to proclaim to “the [Vatican] city and the world” that this six-year-old diocese finally has a seat of power, but he dispatched Cardinal Fernando Feloni.

One hymn says it all. This is a joyous day “the Lord has made”.

But when the music stops, Archbishop Thomas Msusa of Archidiocese of Blantyre, chairperson of the Episcopal Conference of Malawi (ECM) paces to the pulpit and renounces amendments of penal laws that restrict termination of pregnancy except when the life of the woman is in danger.

“If we accept that change of laws on abortion then the future of this church will be bleak,” he weighs in, explaining: “The next generation depends on us taking care of the children and the unborn. Therefore, let us stand against those campaigning for this law because our life is a gift from God.”

On Saturday, the faithful, led by the men of the robes and mitre, nodded as their leader warned against the Termination of Pregnancy Bill activists envisage saving girls and women who die using sharp objects, toxic concoctions and unskilled hands to eject unwanted foetuses.

Traditionally, Catholics uphold the Christian conviction that life begins at conception and must be protected until death.

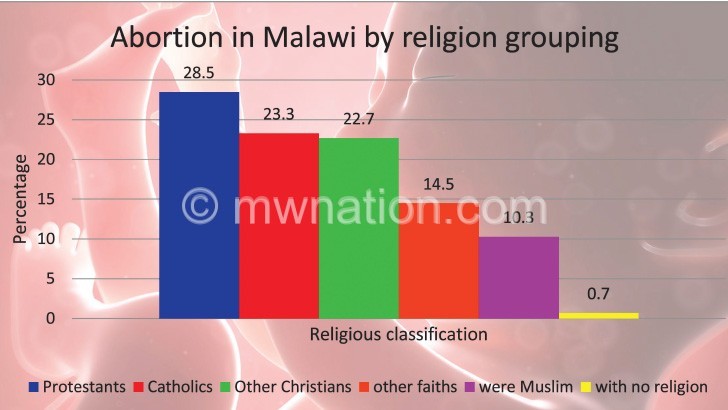

But tallies in hospitals show the church contributes the second largest number (23.3 percent) of women who seek abortion.

Nonetheless, Msusa’s oration against “deliberate killing” echoes the March 2 pastoral letter of ECM in which the bishops censure trends promoting “a culture of death instead of life”.

The faith leaders, who were represented on the special law commission that drafted the Bill, have exempted all health facilities under Christian Health Association of Malawi (Cham) from termination of pregnancy.

However, unsafe abortion keeps haunting women and girls. In 2009, a government study on the incidence and magnitude of abortion revealed that nearly all over 70 000 women who terminate pregnancies every year belong to some religion. The clandestine abortions reportedly kill 17 in every 100 girls and women who succumb to maternal complications.

The official figures subtly confirm that sermons and legal restrictions will not stop a woman from eliminating an unwanted pregnancy if she decides to.

“The figures are frightening and the cost is huge,” says Dr Lastone Chikuni, the reproductive health manager in the ministry which spends nearly K300 million treating post-abortion complications.

His office reports that health facilities in Karonga have handled 3 676 patients almost dying of aftermath of unsafe abortion.

Even the faithful die

The official put the latest figures from the setting of Msusa’s sermon on “grave moral disorder” in context: They tallied 1 047 cases in 2013, 1 008 in 2014, 1 010 in 2015 and 611 this year.

“The majority of them are rural women. Usually, they come to hospitals in a very critical condition,” he told the press recently.

Karonga district health officer Dr Khumbo Shumba asked for more time to verify the number of women who were lying in agony on Saturday.

However, health workers at Karonga District Hospital near the new cathedral say they see “two or three dying women” a day.

The source said: “Religious leaders, especially men, have been condemning abortion for years, but women are still suffering terrible conditions. This will continue unless we take a new approach to confront this problem.”

The immensity of the challenge is clear in complications exerting pressure on a healthcare system hit hard by high disease burden, underfunding and staff shortages.

Almost 70 833 women have sought post-abortal care for the past four years. The neglected crisis accounts for 18 448 women and girls in 2013; 19 777 in 2014, 20 196 in 2015 and 12 412 this year.

The pregnancies being terminated in risky spaces with no skilled health workers in sight partly made the country miss the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) targets to slash maternal deaths to no more than 155 out of 100 000 live births by last year.

By the deadline of the global goals last year, pregnancies were claiming about 570 lives in every 100 000 babies born alive.

With 23 out of 100 sexually active women-aged 15 to 44 years old-procuring abortion, the most tragic thing is not that 80 percent of them are married or that a negligible population do not belong to any religion.

Twenty three is the number of Catholics among every 100 women queuing for illegal abortions aware of “thou shall not kill”, one of Ten Commandments hewn in stone.

The main tragedy is that unsafe abortion is the fourth major cause of maternal deaths after bleeding, sepsis and hypertension.

Among concerned health workers, Northern Region zone manager Dr Owen Msopole told The Nation the silent carnage could be graver as some either conceal their agony or die in silence due to restrictive laws, cultural taboos and religious don’ts that label those who terminate pregnancy as murderers, sinners and misfits.

Colonial laws still kill

But the country’s penal laws, a relic of British colonial rule drafted in 1861 and brought to Malawi in 1929, only allow termination of pregnancy when the life of the mother is in danger.

Such is the weight of religion and culture that they harness the hardship of women of girls to insist on the status quo and veto the Bill crafted by a special law commission established in 2012.

An activist urges those opposed to the law to read the writing on the wall.

Says Coalition for the Prevention of Unsafe Abortions policy officer Luke Tembo: “This debate over morality has not helped reduce preventable deaths and injuries due to unsafe abortion. The problem demands a practical response.” n