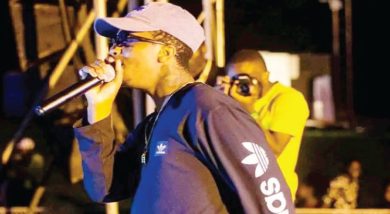

Amazing poet

Remember the famous ChiTumbuka poem Pala Nawona Nesi (When I see a Nurse)?

That is the work of Norman Nyirenda—a vernacular poet whose life is a paradox.

He is a Tumbuka who writes and recites poems not just in his native language, but also Chichewa and, surprisingly, Chiyao. He has, so far, written over 100 poems.

Despite writing poems for years, Nyirenda says he distributes his works for free because he writes for fun.

He is a University of Malawi (Unima) Chancellor College graduate in Humanities majoring in English and History. However, you won’t find him in class. He has been a politician, spokesperson of Alliance for Democracy (Aford) but, he says, he want to end up as a pastor.

Beyond that, he has been a trade unionist, a banker and once worked as a customs officer at Malawi Revenue Authority (MRA). What is more, Nyirenda says he also holds a Class C soccer coaching licence.

“Yes! I have got a qualification in different fields, but I see no qualification for one to be a writer. What matters is enthusiasm,” says the man who, today, calls himself a customs clearing, forwarding and warehousing consultant.

Nyirenda underlines he writes for fun.

“I demand no pay for my creativity and I don’t mind people copying it online without my consent,” he says.

Nyirenda—who comes from Malondanimaso Village, Traditional Authority Mwankhunikira in Rumphi District—started writing fiction while in primary school.

He says his English teacher at Rumphi Secondary School, the late Dorothy Mtegha, encouraged him to continue writing fiction. While in Form Two in 1975, he says, he became the school magazine editor and a year later won the National English Writing Competition.

What makes Nyirenda an amazing poet is his urge to trudge on with vernacular poetry—a field shunned by many. Equally surprising is the fact that his poetry is in different vernacular languages.

How did he get to this?

“I grew up amongst the Yao, Lomwe, Chewa, Mang’anga and Tumbuka people. I write in these African languages to show people the beauty of our African languages,” he says.

Adds Nyirenda: “Our languages are not and have never been inferior to any colonial language as indoctrinated by the British. For us to learn their language we had to pay school fees. They never wanted to speak or associate, in any way, with a black man unless they wanted to be carried on Machira.

That is why, continues Nyirenda, today all French, Portuguese and indeed Spanish colonies speak their former masters languages without going to school.

The British never wanted us to know their language and if you insisted to know their language they asked for tuition fees, he says.

“Look around for the British administrators homes, you will see that they built their homes far away from the African communities. The roads they built were never meant for Africans to visit each other, but were designed to transport the many natural resources they had stolen from us. That’s why all roads and railways ended up at a sea port,” he says.

Nyirenda underlines that his poetry aims at bringing back Malawi’s lost heritage.

“My audience is Malawian to begin with. Anything cultural is best expressed in that culture’s language. I don’t write for money. I write to understand myself, my people and the world. If in return my people and the world read my mind and discover their hidden selves, I’m happy and it gives me joy,” he says.

Now he is working on an anthology of his poems.

Among the popular ones are Wadyabudu done in ChiYao and Chindere Chane in ChiTumbuka.

In Wadyabudu, Nyirenda tells a story of a trickster who met his fate.

Chindere Chane, however, is a poem of sorrow.

Nyirenda tells a story of parents quering a villager who killed their mentally deranged child. n