Corporate social accountability matters

Signed and sealed, community development agreements mark a desired breakaway from ambiguities of corporate social responsibility.

———————————

Atupele Muluzi’s slim-fit suits set him apart from the blur of potbellied ministers and VVIPs clad in routine office wear fraught with fashion offences. The youthful former minister responsible for mining and natural resources was always in the news, talking about government’s commitment to safeguard citizens and nature while exploiting diverse endowments for national development.

“Pardon.”

“Why is everyone talking about corporate social responsibility these days?”

“Either Malawians are learning to demand more from investors or it’s just the civil society at work,” answered M’mbelwa, who spent years in the banking sector where companies rarely give to communities without mentioning the term often abbreviated as CSR.

If Muluzi had been just another person, the ‘high-table joke’ would have gone unnoticed.

But the truth is the cries from communities surrounding mines have almost clichéd calls for greater CSR to lessen gaps in access to basic services that governments ought to provide for its citizens.

As it were, CSR is one of the things profit-seeking companies often do to prop up their image as responsible citizens; caring, empowering, growing with the people and having their exploits told to a wider audience by the press.

In the extractive industry, however, prevailing let-downs require disgruntled locals to shift from CSR to community development agreements (CDA).

“It is no use having companies deciding what they want to do for us without hearing our voice on what we really need,” says Yohane Mwamuyala of Sulo Village near Kayerekera Uranium Mine.

There may be differing perspectives how the country’s largest mine is grappling to live up to the expectations of neighbouring communities, but the underserved community members remember vividly how the talk of CSR began.

“It was in 2004 when Paladin officials came to the village, met with us under a tree and promised to bring development of our choice. We chose a health centre because the nearest, Wililo, is located 18km away,” says Shubert Mwesu.

Village Head Sulo is no fan of the wait. He set aside a piece of farm land for construction of the healthcare facility.

“Two years ago, I reverted to growing maize and cassava on the land because the promised health facility is nowhere,” the village head says.

He remembers meeting Paladin officials several times, including at one meeting where Jim Nottingham came with district health officer saying all necessary designs were ready.

–Minimum requirements–

The promised designs and budgets for the project were far below minimum requirements for a health centre, the Ministry of Health indicated.

“We were in the dark. We made an agreement without knowing how to follow up on the issues and where to take our complaints,” Mwayabala says with regret.

But Mweso candidly confronts the dilemma: “The main challenge is that the agreement was verbal.

“They came, wrote down what we wanted and we allowed them to leave without signing any binding deal. It’s all verbal and we have nobody to blame but ourselves”

With no deal sealed and signed, Paladin has directed its CSR towards building two school blocks and teachers houses at Kayuni Primary School; painting the rusty rooftops of classes and repairing an under-five clinic at the bottom of the hilltop mine.

Today, the locals still carry patients on their back, on bicycles and in wheelbarrows all the way to Wiliro Health Centre.

Centre for Environmental Policy Advocacy (Cepa) is one of the organisations empowering affected communities and the civil society to entrench responsive governance and win-win deals in the extractive sector.

Project coordinator Cynthia Simkonda supports the breakaway gaining momentum that binding community-investor agreements could be more helpful than charity-like CSR.

She says investors’ lack of interest is compounded by the Mines and Mineral Act of 1981 which does not stipulate how much mining companies should be investing in developing communities.

“The downside of CSR is that it leaves the locals at the mercy of the investors. Rather than waiting for what looks like acts of goodwill, some countries are taking the approach of community development agreements which are negotiable and binding,” Simkonda told Karonga citizens in February.

Taking this path, village heads surrounding Mwaulambo Coalmine and Eland Mining Company signed a deal at Karonga District Council which obliges the firms to upgrade an unpaved road that branches from M1, construct a health centre and school blocks in the area.

Asked about the impact of the Karonga accord, GVH Mesiya stated that it is a vital tool for transparency and accountability despite serious setbacks that would be history if mining laws were amended to give the locals a voice on issues affecting them.

“It indicates what we resolved, what is happening, what isn’t and the way forward. Currently, there are serious breaches largely because our laws make mining companies accountable to central government only and not concerned Malawians as well,” he lamented.

On a dirty road to Mwaulambo, it is clear the locals are getting what he calls “a raw deal”.

–CSR in mining–

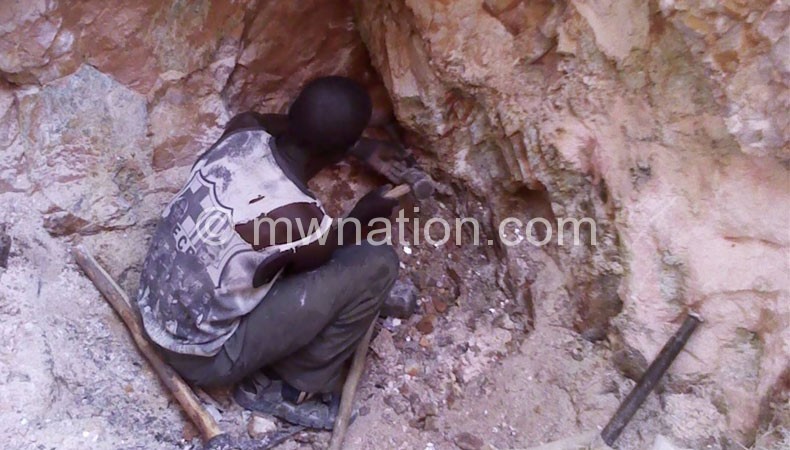

Travelling in the rice fields of Karonga North, you get a glimpse of what mining can do in the absence of stinging laws.

On the unpaved road off Karonga-Songwe Tarmac near Kiwe, the spills of Mwaulambo Coal Mine are all over the place.

For years, Eland Mining Company has been dumping coal waste on the bumpy road, turning the narrow affair into a black strip that contrasts strikingly with the greenness of Ngerenge Rice Scheme all the way to the mining zone.

The idea of offloading unwanted by-products of coalmining on muddy roads to make them passable in the rainy season, until recently, has been regarded with scepticism in public health circles and it remains one of the sticky issues at Mwaulambo.

In his village along the blackish pathway to the coalmine, the yellowish crop flashes past. Agriculturalists often write off the sight of the scorched crop on the roadside as ‘border effects’, but the rural farmer counts it as an immerse loss as the harvest from the plot has been on the wane.

He says the farming communities have been living “on hot coals” since Eland started mining coal in the hills of Mwaulambo eight years ago.

But it is one of the many burning issues that overshadow the mining activity that began with sights of local experts and expatriates taking samples and exploring the availability of the fuel mineral.

When asked about the coals, the locals say they were sidelined from the start.

“We just saw the mine taking shape,” says Brenda Mwalwimba. “After years of getting our coals, nobody seems to care about our interests even though we are the worst hit by the side effects of the mine.”

The rural community’s confidence in mining companies and government has dipped to a new low, they say.

When asked about the ailing relationship, GVH Mesiya stated: “When we heard the rumours and murmurs of Eland opening a coalmine in our area, we were very excited. We thought it would bring more jobs for our children, more customers for our rice and more money for our government.

–Loyalties from mining–

“Government may be getting its loyalties from the mine, but it has left people with a bitter aftertaste of how mining forces poor people out of the land they have been occupying for years and how it destroys the environment.”

The rumble on the coal-surfaced road reflects the legal pitfalls that blight the country’s ongoing walk towards people-centred mining practices.

It also demonstrates the Malawian mining context is not apace with rapid changes of mining guidelines as have other countries on the continent.

Yet, the impact of mining on the environment and people’s wellbeing are a significant area that must safeguarded by sustainable laws and policies.

Mining generally affects the environment and natural resources—land, air and water.

The country’s environmental management policy singles out safe waste disposal as one of the guiding principles when it comes to environmental management in mining.

Apart from ensuring “a safe and healthy operating environment for mining production”, firms have an obligation to guarantee a clean environment for surrounding communities.

Spelling out the sanctions, the environmental policy states: “The ‘polluter pays’ and precautionary principles shall be used in the design, implementation and monitoring of mining projects.”

‘Polluter pays” is a rule which binds those in breach of the Environmental Management Act of 1996 to pay for the life-threatening consequences of their acts.

This is the principle Muluzi evoked on January 10 amid concerns over leakages at radioactive material at Kayerekera Uranium Mine in Karonga.

“If there is anything to suggest breach of the country’s laws, government will make sure that Paladin pays the full price,” said the minister, standing by the Australian mining firms’ stance that all is well at the mountaintop mine in Karonga North West.

Like the civil society, the environmental policy requires government to revise the Mines and Mineral Act “to harmonise it with other sector policy and legislations and make it more investor-friendly”.

A review is underway to update the mining law which is roundly criticised as outdated and out of touch with acceptable mining practices as well as lingering community concerns.

But safe-guarding locals and nature in mining areas matters as much as the interests of wannabe and existing investors.

In their own words, honouring corporate social responsibility makes mining firms truly a part of the affected communities.