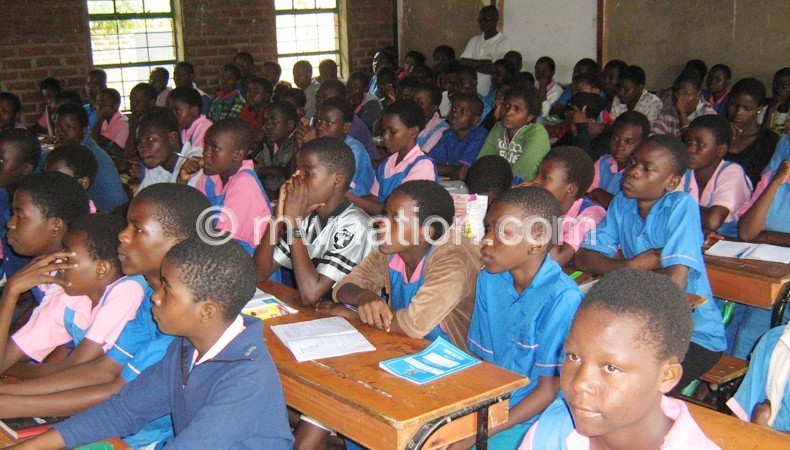

Creating accountable schools

Closing existing gaps in primary schools could create graver gaps in the absence of checks and balances. JAMES CHAVULA writes.

Everyone is talking about quality education. But in Chitipa, they say quality is unattainable without transparency and accountability in the running of school initiatives.

“To achieve quality education for all, everyone needs to know what is happening and their roles in making it happen. They need to take part,” says group village head Mwenishakila.

To the traditional leader, building transparent and accountable schools is not just about empowering school management committees (SMCs) and parents and teachers associations (PTAs).

It is also making sure that every citizen has information and power not just to mould bricks, collect sand and provide water for construction of school blocks, offices and teachers’ houses.

They want a say when it comes to identifying drawbacks to quality education, a hand in conjuring up plans to eliminate the gaps and an eye on how recommended interventions are implemented and how funds are used.

However, an inquiry into school improvement funding in Nthalire has exposed the proponents of ‘glass-walled schools’ have to endure a long walk to embed transparency and accountability in the education sector.

In their minds, the brains behind the grant saw efficient use of the funds creating an enabling teaching and learning environment in constrained schools.

The planners at Capital Hill wanted the grant supporting the national education sector by enhancing the quality and relevance of education on offer, access and equity in schools as well as governance and management of the sector often touted as a key to a brighter future and national prosperity.

On the ground, change is discernible: Schools with grass thatches, mud walls and dusty floors now have brick and-mortar classrooms roofed with iron sheets.

Those with inadequate teachers attending to over 60 pupils each can afford stipends for volunteers lending a hand; rural institutions with no electricity have installed solar power systems to enable boys and girls ample study at night; and orphaned and vulnerable children receive uniforms and other school materials.

Good, isn’t it?

This might be commendable, but a voice of concern is rising that closing the gaps in the education sector could actually create graver gaps and inefficiencies unless the existing secrecy is shattered and loopholes are sealed.

“The grant is transforming schools, but it can do better if properly managed and subjected to more checks and balances,” says District Education Network (DEN) chairperson Sydney Simwaka.

Recently, the network, with support from Malumbo community-based organisation and ActionAid, visited 10 out of 32 schools in Nthalire to assess utilisation of the school improvement grants.

The findings?

“For the programme to be a success, there is need to enhance community involvement beyond SMCs and PTAs,” the report reads.

The community are not excluded by widespread unawareness of their roles or unwillingness to contribute towards creation of better schools.

Only signatories of cheques— headteachers as well as chairpersons of SMCs and PTAs— are usually actively involved in the running of projects.

Simwaka aptly terms this a critical accountability lapse, warning: “This can facilitate abuse, [especially] collusion among the signatories, and discourage community involvement and transparency.”

Of the randomly selected schools surveyed, only PTA and SMC members at Chithi reported being periodically briefed on how the money is being used.

In the findings, minefields of abuse are all over the place. Committees spending the money on priorities not stipulated in school improvement plans.

Village and area development committees expressing ignorance of how the grants are used. No independent audit of transactions. No school displaying the plans, activities, funding, budgets and expenditures on notice boards.

However, the most farcical scenario includes the raging debate on uncertainties over repayment of about K190 000 ($345) four schools borrowed from Kamphyongo Primary School six months ago.

Nthalire Local Education Authority School SMC chairperson Chafwa Mtambo says they repaid the money to officials at the office of district education manager (DEM), but the DEM says he is still awaiting the refunds.

According to Mtambo, this is the “whole truth”: In April, procurement committee members from Nthalire, Benthu, Chinthi and Guya left for Chitipa Boma to buy goods for their schools.

“On arrival, we were all shocked to learn that our accounts were empty. Fortunately, the DEM graciously made arrangements to lend us K24 000 from Kamphyongo for accommodation and refunds. We repaid the money as soon as we received our allocation of K272 012,” the official whose school used the money for installation of solar power and uniforms for pupils from poor background said.

But, the DEM, Fanwell Chiwowa, who attributes the ‘borrowing’ to lapses in the banking and integrated financial management system (Ifmis), says he has not yet received the reimbursement.

In an interview, Chiwowa explained: “I wouldn’t call it borrowing as such. When processing the grants, schools under the same bank are handled together.

“All the money for schools that claim to have borrowed went into the account of one school. They were expected to pay back the money they got on trust. They didn’t.”

The unresolved “human error” offers a glimpse of slips in the grants often derailed by delayed disbursement as prices of goods soar.

At worst, pupils go without classes when teachers, who sit in procurement committees, travel to Chitipa Boma to buy goods.

Yet, the loose ends in the “borrowing arrangement” are just a glimpse of the sticky issues that require the district education office to act decisively.

At Msongolera Primary School, a head teacher, who is enduring uneasy ties with the SMC and PTA over the grant worth K610 406 ($1109), refused to disclose how the money was spent despite asking for a week to study the questionnaire.

At Kalowe, an assistant coordinator could not provide records of the funds because there were no handovers since the previous primary education adviser got promoted.

Likewise, a headteacher at Chiguza could not provide details reportedly because his predecessor did not make handovers and took away all the files when he was transferred to Mukule. His deputy went to Kamilazovo.

The DEM, who faces the challenge to ascertain whether the funds were used for the intended purpose, described shoddy record keeping and handovers as worrisome.

“We’ll thoroughly investigate the incidents and take appropriate action. My office does not transfer head teachers in the middle of primary school improvement projects. Besides, it is unusual for civil servants to leave without handovers. They are required to do it,” said Chiwowa.

Ensuring transparency and accountability is one pillar of Action Aid’s 10-point charter for promoting rights in schools.

According to Action Aid district project coordinator Wongani Mugaba, nearly all schools in the district are not fully rights respecting.

“Some may meet a number of the benchmarks, but come short of small steps like accounting to decentralisation structures and displaying public information on notice boards for all to see,” Mugaba says.

For the locals, the quest for rights-respecting schools with systems for community involvement, accountability and transparency, will empower them to keep track of decisions and expenses made in their name and pupils’ wellbeing.

But district council chairperson, councillor Isaac Mwepa, says the opaque systems exposed could be symptomatic of widespread inefficiencies and leakages in the district.

“If we are serious about quality education, we need to ensure every tambala meant for education is put to educational use,” says Mwepa.

The councillors and activists want the money back to the education sector, they asked for ring-fencing of education funding.

The council also wants answers on how constituency development funds amounting K15 million ($27,272) was diverted with reportedly K9 million ($16,363) going towards council operations and K6 million ($10,909) to the district health office.

“This impunity has to stop. Those who embezzled the money have to pay back. We cannot keep denting the image of the district when it comes to accountability and transparency issues,” said Mwepa.

Nthalire Area Development Committee chairperson Rowland Kasonda reckons periodic and extensive evaluation of education funding would restore sanity.

There is need to rally villagers to take the lead in demolishing the thick walls of secrecy, Malumbo director Charles Mfune said.

Since 1995, Malumbo has been working towards empowering the youth, children in poverty and rural schools around Nthalire overcome effects of HIV and Aids.

In an interview, Mfune said community sensitisation is inevitable.

He explained: “The findings confirm what rural Malawians have always feared: We will never deliver quality education to poor pupils in remote schools unless citizens are empowered to make sure there are no leakages in funds meant to improve the learning environment. Things have to change.” n