Dying lights, sticks and syringes

A dimly illumined darkroom produces vivid pictures of cracks that need sealing to improve post-abortion care, JAMES CHAVULA writes.

A sprawling corridor takes visitors to a busy maternity section of Salima District Hospital where women expect every pregnancy to bring them joy.

But there is no light at the end of this tunnel, for pregnant women who abort clandestinely or miscarry.

Their lengthy passageway takes them to a cell-like darkroom where nurses and clinical officers, armed with giant syringes, conduct manual vacuum aspiration (MVA).

This is a procedure required to clean wombs of women suffering devastating complications of incomplete abortions, including miscarriage.

But the MVA room is utterly shadowy, with frail rays of an ordinary energy-saver bulb illumining a patient lying on a rickety surgical bed.

But the low-energy bulb, meant for home use, perfectly shines the light on a hugely worn out mattress where clinicians need brighter rays as they insert the massive syringe in a woman’s uterus to extract the remains of incomplete abortions.

Fresh bloodstains were visible on the threadbare mattress that silently speaks of lapses in the way the country treats women with life-threatening complications.

—No way through?—

A half-full bucket of blood, perching in a dimly lit corner, further confirms that a woman in agony had just been saved from preventable death a few minutes earlier. It emitted a putrid smell, for most women in need of the procedure arrive at the hospital bleeding heavily, with their uteruses severely punctured and rotting.

Welcome to the darkroom which offers vivid pictures of the agonies of clandestine abortions often done in unsafe spaces. The sticks and holes in women’s uteruses offer shocking evidence of women harming themselves to beat colonial laws which only allow abortion when a woman’s life is in danger.

“Welcome to Salima, but you are not allowed to go into the MVA room. Only medical personnel are allowed there,” said district safe motherhood coordinator on our arrival.

But it is not a no-go zone?

“Every day, three to five women and girls come into this room for urgent attention,” says clinician Misheck Wilson.

He has been providing post-abortion care for 21 years. His career got off to “an exciting start” at Banja La Mtsogolo, the local chain of Marie Stopes clinics which are better equipped to provide sexual and reproductive health, including MVA.

Since 1991, he has numerous girls and women who were likely to die if he was not skilled and ready to assist.

“The majority of the patients end up in the MVA room with their uteruses pierced by sticks or wires in the process of inducing abortion. They all claim to have miscarried spontaneously, but this is just an excuse since the abortions is outlawed in the country,” he says.

Restrictive laws

The country’s penal laws prohibit health workers from terminating pregnancies unless the woman’s life is in danger.

Despite ambiguities and uncertainties on what actually constitutes grave threat to life, the decision can only be reached in consultation with two or more doctors and they are only allowed to conduct surgical abortion.

The insistence on surgery does not take breakthroughs in medicine.

In the country, pills for inducing labour and abortion are available without prescription and at as low as K2 500 in any roadside drug store.

It also mirrors the restrictive nature of the country’s colonial abortion laws.

But the majority of women who seek post-abortion care in the country’s hospitals confirm that the tough laws, currently under review, have not stopped women from terminating pregnancies they decide not to carry anymore.

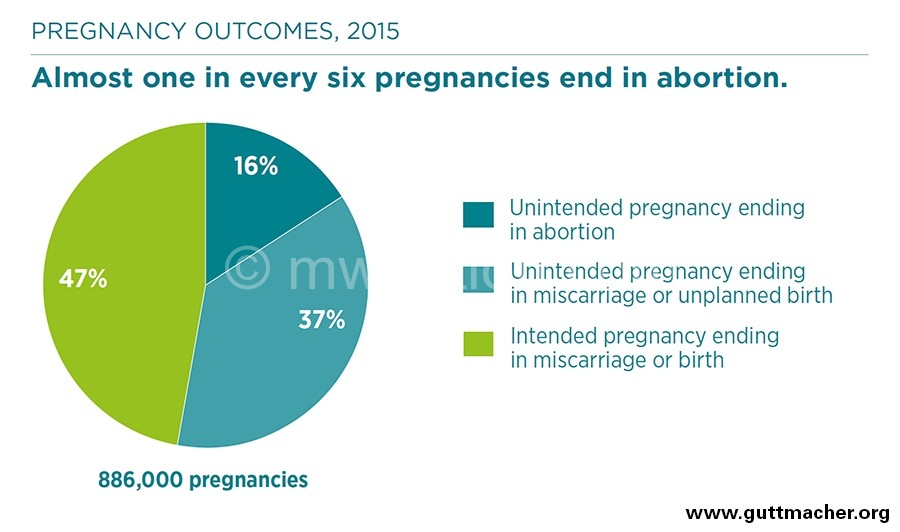

“Each year, 141 000 Malawian women have abortions, almost all clandestine,” reads a recent study by the Centre for Reproductive Health at the College of Medicine (CoM) in Blantyre and the Guttimacher Institute in the US.

The new evidence from the two sexual and reproductive health think-tanks coincides with a heated debate over the State-backed push to increase grounds for which women can terminate unintended and life-threatening safely and legally.

Nearly 60 percent of abortions result in complications that require medical treatment, according to the researchers.

However, the situation at Salima District Hospital offers a grim glimpse of how under-quipped health facilities in the country are when it comes to handling these deadly and clipping effects of backstreet abortions which are usually unsafe and associated with up to 18 percent of women dying of pregnancy-related conditions.

“The major problem is that very few nurses and clinicians are trained to provide post-abortion care. They work in a room which is not properly equipped for the procedure.

“In the MVA room, we are using a bulb not fit for clinical or purposes. The bed and mattresses are old. We have two old syringes which are few,” said Biliati.

This leaves patients at risk of catching uterine and blood-related infections because the health workers are so overwhelmed by the influx of patients that they hardly have time to sterilise the syringes, said the nurse.

“When one is still in use, the other is supposed to be under sterilisation. But there are times we don’t have time for the safety measure. This puts women in danger of contracting infections of the uterus from previous woman,” he explained.

Nothing unusual

Similar concerns were clear when legislators belonging to the Parliamentary Committee on Health visited Mwanza District Hospital and Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital (QECH) last year.

Providers of post-abortion care at QECH in Blantyre spoke of overwhelming caseloads from nearly all districts in the Southern Region, saying they sometimes use unsterilised tools although the referral hospital is better equipped than district facilities.

According to the health workers, many patients from rural areas arrive too late to live.

The bleak picture resembles what Mwanza West legislator Dr. Paul Chibingu encountered when he was learning the ropes at the largest referral hospital in the South.

“When I was a young, we used to treat 20 to 30 women, with some queuing outside the MVA room while were hard at work. Has anything changed?” asked the doctor-cum-politician who founded Mtengoumodzi Hospital in Blantyre.

Not much has changed though, they chorused.

A nurse in the group said it all: “Every day, we have 15 to 20 cases. Women and girls still queue to have their wombs cleaned up. Sometimes, we run out of syringes and other equipment. The women wait in pain as the tools have to go and be sterilised to safeguard the clients from infections.”

Chibingu seemed at home when he returned to the hospital where he sharpened his skills shortly after obtaining his diploma in clinical medicine in 1997, but he minced no words about women dying of induced abortions and gaps in post-abortion care.

“As lawmakers, we are not here to debate whether or not to libaralise abortion laws. We will have our say when the Bill comes to Parliament. For now, we need an open discussion on what we really need to do something about the situation. How can we help you to ease your work of saving lives, including those coming for post-abortion care?” he told the health workers.

A consensus was clear: abortion-related workload in the interiors of QECH, which receives critical patients from Mulanje, Thyolo, Chiradzulu, Blantyre, Chikwawa and Nsanje—is nothing to smile about.

Treating complications resulting from incomplete abortions often done clandestinely and assisted by unskilled hands are exerting pressure on the healthcare system already struggling with underfunding, high disease burden, shortage of skilled staff and rapid population growth.

Almost a third of cases in the ICU at QECH are related to abortion complications. Most of them come too late to live and government pays huge bills as they are mostly relocated to the ICU of the privately-owned Mwaiwathu Hospital to pave the way for patients with other conditions.

Gaps persist

Since 2003, the Ministry of Health has increased the number of public facilities providing post-abortion care, upgrading some clinics and trained more providers.

Although use of manual MVA for treatment of incomplete abortion is recommended by the World Health Organisation (WHO)—recommending the use of dilation and curettage (D and C)—recent studies have documented declining MVA use in post-abortion care in selected hospitals in Malawi.

“In our study, when asked how treatment for abortion complications could be improved, 74 percent of respondents said “have more commodities available” while 64 percent said “have more trained people available,” report the researchers from CoM and Guttimacher.

According to the findings, addressing availability of equipment, providing regular training, and addressing staff shortages could improve post-abortion care in the country.

“Expand post-abortion care services by guaranteeing that all health facilities are fully stocked with the necessary medications, supplies and equipment to provide this care and [ensure] that staff is trained in how to provide post-abortion care according to WHO guidelines,” they recommend.