Floods water silent border spat

Malawians in Makhanga, Osiyana and surrounding communities face deepening frustration and uncertainties as floods that ripped the northern part of Nsanje last year have left them almost landless.

The locals are disgruntled by government’s sluggishness as they grapple to reclaim their land which was cut off and buried in sand due to the disaster.

“We feel abandoned. How can government keep mum as we suffer abuses from Mozambicans?” asks Ruo Ward councillor Maliko Molotali.

The rural farmers pay neighbouring Mozambicans thousands to access the crop fields and grazing zones on the eastern banks of Ruo River.

The survival of these Malawians in the flood-prone border region is in the hands of the neighbours.

For them, the lost land was their most prized asset—the main source of livelihood.

The councillor says: “The 2015 floods damaged most of our farmlands and buried them in sand. We can’t grow crops on it.

“We now farm in Mozambique, but at a cost. We are asked to pay rentals. When our animals graze on their pasture, they capture them and fine the owners.”

Makhanga and Osiyana residents have lived this way since April last year when the tragedy struck, changing the course of the Ruo, the border between the two countries.

The river, which originates from Mulanje Mountain, now flows deep into Malawi. Vast fertile fields, estimated at 100 hectares, now fall on the Mozambican side.

According to international agreements, all land east of the river belongs to Mozambique.

The shifting of the river is worsening the livelihood of pastoral Malawians impoverished by chronic floods.

“Several times, Mozambican authorities mounted their national flags on our soil. They wanted to claim the whole area, but we engaged authorities and they stopped.”

However, the mood remains tense and uncertainties are deepening.

“If they capture our cattle grazing that side, they fine us K10 000 per animal,” laments Traditional Authority (TA) Mlolo.

For years, Lilongwe has been engaging Maputo to put beacons on the watercourse Ruo created over a century ago.

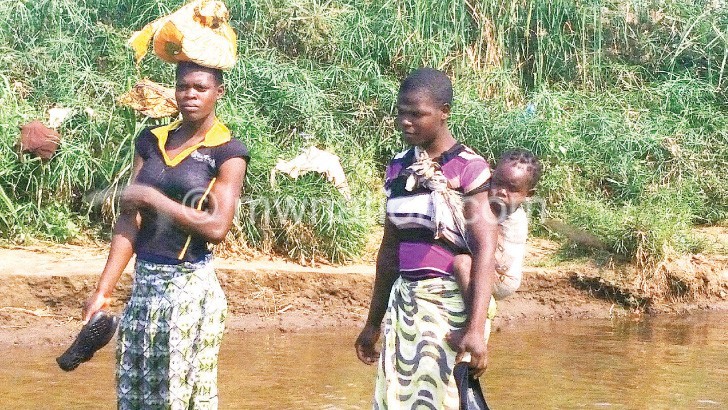

Currently, Malawians on west banks of Ruo have been cut-off and accessing vital services—including schools, Makhanga Health Centre and Makhanga Trading Centre—is not easy.

In some spots, the locals pay up to K200 each to boatmen who ferry them across the Ruo.

“The water levels have fallen drastically. In some areas, people cross the river on foot. When it rises, we make up to K5 000 a day,” says Justine Libani, one of the boat operators cashing in on the calamity.

Our minibus got stuck in the sands. Only off-road cars, the four-wheel drives, reach Makhanga. Only motorcyclists do. The seven-kilometre trip from Osiyana Junction to Makhanga takes about 40 minutes of splitting the sands to get there. It costs K3 000 per passenger.

Nothing has happened following early calls to move Ruo River back to its original course.

Commissioner of disaster management Ben Botolo and Department of Disaster Management Affairs (Dodma) director James Chiusiwa and other government authorities were welcomed by angry locals when they visited the area last week Monday.

Officials from the Department of Water told Botolo that they communicated the border shift on time, but no action was taken.

“Rechanneling the river is not a big job. We reported when the river had not dug deep into the current route. Had we acted that time, this problem wouldn’t have been this bad,” explained Pepani Kalua, the deputy director responsible for surface water development.

He reckons there is need to construct a dyke to prevent flooding.

Botolo echoed the need to act swiftly to save the cut-off communities from worse hunger and poverty.

He said: “Our people are experiencing abuses from the neighbours. If we don’t do anything the soonest, our land will be in Mozambique. In future, they might have a claim that it is their territory. It is just a matter of urgency to reopen the old channel.”

He revealed that government, with funding from the World Bank, has done studies on where the beacons should be.

“The pressure is on us. In case of another flood, lives of people at Makhanga will be at risk. We need both the dyke and re-opening the old channel,” Botolo said.

Amid the professed desire to act, pain, grief and fears for another flooding are deepening.

Meteorologists have already forecast heavy rains in the southern region and potential floods. n