Keeping teachers in rural schools

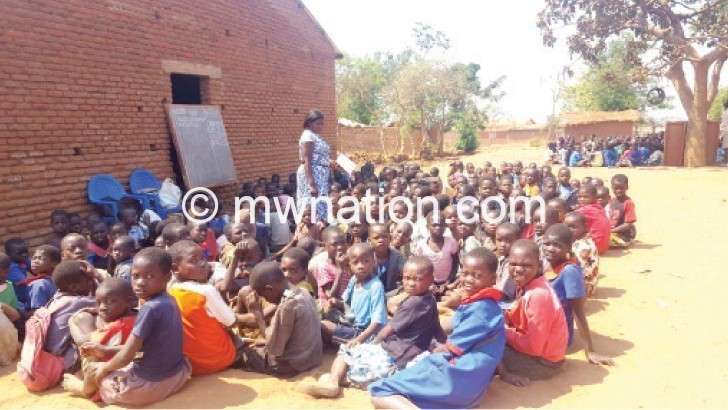

Alberto Gwande and almost 800 pupils at Khuzi Primary School in Lilongwe need more teachers. The school is severely understaffed, with only six teachers.

“I was supposed to receive new teachers last year, but they never came,” recalls the head teacher.

Khuzi is 20 kilometres away from Nathenje Trading Centre. Its pupil-teacher ratio (PTR) is 131 pupils per teacher.

In contrast, a teacher at Chibubu, four kilometres from Nathenje, teaches 65 which Mwatibu school nearby has a PTR of just 49.

Despite the shortage at Khuzi, it was Chibubu which received four new teachers last year.

Unfortunately, this situation is not uncommon.

The country spends almost 80 percent of its basic education budget on teachers’ salaries, but its 61 000 primary school teachers are very unevenly distributed.

In a single district, PTRs can vary from below 10 pupils per teacher to above 100 in extreme cases.

The variation is highest between remote schools like Khuzi and those closer to towns and large villages, such as Chibubu and Mwatibu.

Remote schools typically have fewer facilities and poorer pupils. These staffing gaps exacerbate existing inequities in the system and low learning outcomes.

Only 31percent of pupils who enter primary school complete it and they perform poorly. A regional assessment in 2013 showed that most Standard Four learners are unable to pluralise the word “mango” or solve “100 + 20”.

Malawi’s problems are not unique. According to World Bank’s forthcoming regional report, in most African countries at least 20 percent of the variation in teacher allocations between schools is unexplained by variation in enrolment. In some countries, the figure is as high as 85 percent.

These inefficiencies contribute to Africa’s learning crisis: in five out of seven countries participating in the Service Delivery Indicators (SDI) programme, fewer than 10 percent of fourth graders could read a paragraph in the main national language and fewer than 20 percent could read a sentence.

The SDI is an Africa-wide programme that collects facility-based data from schools and health facilities every two to three years. The initiative is a partnership of World Bank, the African Economic Research Consortium and African Development Bank.

A problem of data

The persistent inequities in Malawi reflect problems with the administration of teacher allocations. Until recently, data on the whereabouts of teachers was fragmented and inconsistent between government agencies.

As a result, teacher allocation policies are inconsistently enforced. All schools with a PTR above 60—three out of every four schools—have been eligible to receive new staff each year. Teachers apply pressure through formal and informal channels to avoid being placed in remote schools.

In the absence of reliable data on PTRs, officials rarely enforce the rules strictly. A hardship allowance intended to reward teachers working in remote schools is received by over 80 percent of teachers, rendering it ineffective as an incentive.

Data-driven solutions

The World Bank’s education team has been working with government for two years to address these issues.

Working with central- and district-level officials, the task team developed the first up-to-date, accurate and comprehensive database of all Malawi’s primary school teachers and their current school postings.

We analysed the driving factors behind PTR variation: road access to the school, availability of electricity, distance from the nearest trading centre and facilities like banks.

Teachers care most about these amenities when expressing preferences over school postings, rather than provisions like housing which government prioritises.

Using these findings, World Bank developed a new three-level A-C classification of school remoteness, capturing not only physical location but school-level and trading centre facilities. This simple and accurate categorisation captures the key factors which influence teachers to resist placement in schools.

The team developed two policy reforms to rapidly reduce disparities in teacher numbers without any additional costs.

First, the annual deployment of 5 000 new teachers is now being targeted to Category A and B schools—a departure from the previous policy of allocating new teachers to the neediest schools.

Second, reforms are underway to the hardship allowance scheme to achieve the original goal of providing a meaningful bonus to teachers working in the remotest schools.

The improved scheme will provide a monthly allowance of $35.00 (almost K25 000)— roughly one-third of an average teacher’s salary—to 20 percent of teachers working in the most remote schools.

Those in moderately remote schools will receive a reduced amount.

The policy, to be rolled out later this year, is expected to motivate teachers to stay in or move to hardship schools.

Smarter policies

These policies are likely to rapidly improve the distribution of teachers.

According to World Bank analysis, just three percent of existing teachers move to more remote schools to obtain the allowance.

If all new teachers are allocated to more remote schools, PTRs between the most and least remote schools could be nearly equalised within one year.

Evidence from the 2016 allocation of new teachers suggests that the increased awareness of PTR inequities engendered by the project already led to improvements in teacher allocation decisions.

These policies were designed in close consultation with the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology district officials, head teachers and the Teachers’ Union of Malawi (TUM), as well as central ministry officials.

The impact of the improvements in school-level PTR will be enabled by these policies will be subject to quasi-experimental evaluation financed by the Royal Norwegian Embassy through Malawi Longitudinal Schools Survey whose results will be published soon.

Data-driven approaches such as these can facilitate better learning outcomes, maximise efficient use of resources and empower teachers like Gwande and his pupils to achieve more.