Mercy cycles poverty

She is suffering the consequences of a problem she might, in few years, be part of its cause. What is her story? Our news analyst EPHRAIM NYONDO writes as he begins the series on the demographic dividend in Malawi.

|

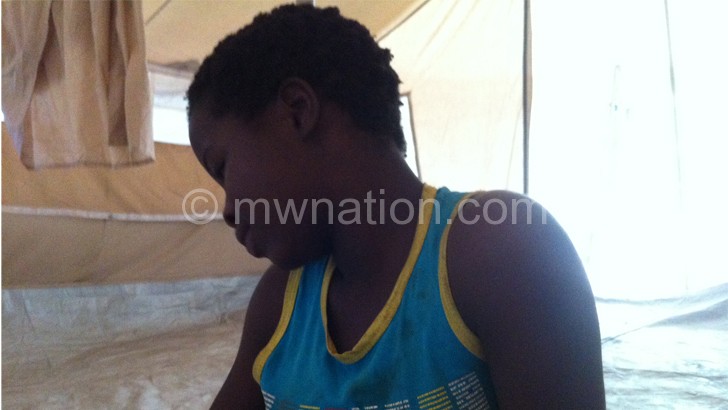

Almost everything about her story is peculiar.

She is turning 13 this September, but she is in Standard One. She is the last born in a family of nine—and the only one not in marriage.

Her elder sisters—as young as 18, 20 and 24—are already married and all of them, already, have not less than two children each.

She, too, could have been married by now. Not once, but twice did she run away from the man she was married to last year.

In fact, an official from a local non-governmental organisation (NGO)—Women Legal Resource Centre (Wolrec)—confided in The Nation that she was married off even before her first menstruation.

Though Wolrec managed to rescue her at first and dragged her parents to court, tradition brought her back to marriage.

Elders in the village, reports show, forced her back to the 18-year-old boy who had already given packets of sugar and other groceries to her parents as dowry.

But it was the forces of nature that saved her from the marriage life she was unwilling to start.

The raging floods that swept her entire village disturbed everything. After the evacuation to the camps, everybody’s focus was family survival—nothing else.

“I could have been, finally, married off if it were not for the floods. But up to now, I don’t want it. I don’t,” she says, with her face down while begging this journalist to take her to ‘town’.

Taking her away could, somehow, relieve her fears. However, that does not take away a critical cause and consequence of the problem her story represents in Malawi.

Mercy Jenala’s story brings into focus how poverty and tradition push young girls into early marriages; how early marriages fuel rapid population growth; how rapid population growth breeds environmental destruction; how environmental destruction causes disasters; and how disasters return people into the same poverty they wanted to solve by pushing young girls into marriage.

Mercy comes from the same Muyang’anira Village in Traditional Authority (T/A) Nyachikadza in Nsanje District with Fasiteni Nyelezelani, 49.

Nyelezelani is married to two wives and, he says, “So far, I have 12 children.” His wives, aged 28 and 30, he adds, are yet to stop giving him children.

“My father married three wives and he had 21 of us. Though I am trying, I am not even close. But I understand that his time was different from us,” he explains.

Though the national fertility rate is currently at an average 5.7 children down from 6.0 in 2004, according to the 2008 Malawi population and housing census, Nsanje’s fertility rate, the same census shows, hovers at an average 7.0 children, birth rate at 50.1 per 1 000 and death rate at 15.8 per 1 000 live births.

The entire spectacle, according to Jesman Chitsanya—a Chancellor College population expert currently pursuing doctoral studies in the United Kingdom (UK)—underlines that Malawi’s population is still high, adding: “Perhaps one of the highest in the world”.

Swedish Hans Rosling, professor of global health at the Karolinska Institutet and a medical doctor who has carried out decades of research in Africa, says as economies continue to grow in East Asia and Latin America, most families are choosing smaller families like in the United States of America (USA) and Europe.

But he notes that while the trend in most parts of the world is for smaller families, the problem is currently in Africa where, he argues, in the next century, it poses a great challenge of adding so may to the global population.

The rise in population, some experts argue, has negative impact on development.

Theorist Thomas Malthus, in his most well-known work An Essay on the Principle of Population published in 1798, argued that increase in population would eventually diminish the ability of the world to feed itself.

He based this conclusion on the thesis that populations expand in such a way as to overtake the development of sufficient land for crops.

For nations to develop, he furiously recommended, they needed to control their population growth.

But not everybody agreed with him.

In a book The Conditions of Agricultural Growth: the Economics of Agrarian Change under Population Pressure published in 1965, Danish thinker Emily Boserup argued that population determines agricultural methods—emphasising that ‘necessity is the mother of invention’.

It was her great belief that humanity would always find a way, consistently arguing that the power of ingenuity would always outmatch that of demand.

In other words, humans, as they grow in population, would develop technologies that would meet their rising demand.

However, Chitsanya argues that there is no straightforward answer to the two [Malthus and Boserup] in relation to the Malawian case. The implicit recognition is that there is not enough to go around for all, and the population growth must go down.

He adds that Malawi’s rapid population growth, at 2.8 percent per annum, poses challenges to the development of the country.

“In that the total fertility rate, which is the average number of children a woman has in her lifetime, remains high, and is declining very slowly. The recent 2014 Millennium Development Goals Endline Survey estimates it [fertility rate] to be at five children per woman, a marginal decline from 5.7 children in 2010 and 6.4 children in 2000,” he explains.

Notably, Malawi’s unabated population rise has already resulted in increased destruction of the environment—in the process accelerating poverty.

This year in January for instance, the entire area of T/A Nyachikadza in Nsanje was completely swept away by raging floods that hit 15 districts in the country.

The area, which is well-guarded by the meandering Shire River, is quite fertile. However, with the rising population, evidenced by Nyelezelani’s story, people are currently cultivating on the banks, which has increased siltation levels in Shire River.

Today, Nyelezelani, Mercy and thousands of others, are still living in camps—homeless.

They lost everything and, currently, they do not want to return to their previous home though none in the upland is willing to give them land to relocate. They are desperate.

Most of these families, like the case of 52 percent living below a dollar a day, are already poor people whose lives are predominantly dependent on subsistence farming.

Still rooted in tradition, most parents marry off their daughters, like Mercy, at an early age in quest of relieving themselves from the burden of responsibility.

The 2010 Demographic Health Survey shows that over half of women in Malawi are married by age of 18, compared with just eight percent of men.

The median age at first marriage, shows the DHS, is 17.8 years for women of 25–49 age range compared with men who marry later, at a median age of 22.5 within the same range.

However, Chitsanya says Malawi’s unabating population rise is mostly due to the challenge of early marriage—that is, marrying off a girl like Mercy at their tender age.

It means delaying marriages of girls like Mercy could be a population dividend for Malawi. But how can Malawi achieve that?

this is a great article. Brings a number of issues to light