One-Day: Uliwa’s dead man walking

In Karonga, young men change names at will—and it is seen as trendy.

But it is not for nothing that one Parodi Gondwe is known as Mr One-Day.

“One day, I will die,” he says. “Life is short and we have ourselves to blame if our final home will be shoddy.”

Since he was five, the 45-year-old has been living like someone who is soon to die.

He likens himself to a bull in a slaughterhouse, saying: “Death is certain and we need to prepare for it.”

This certainty has pushed him to construct a grave in a family gravesite in Mwakanyamali Village and buy a coffin while he is alive.

So did the late SS Ng’oma and Pastor This Man Sasintha Mnozga in Rumphi.

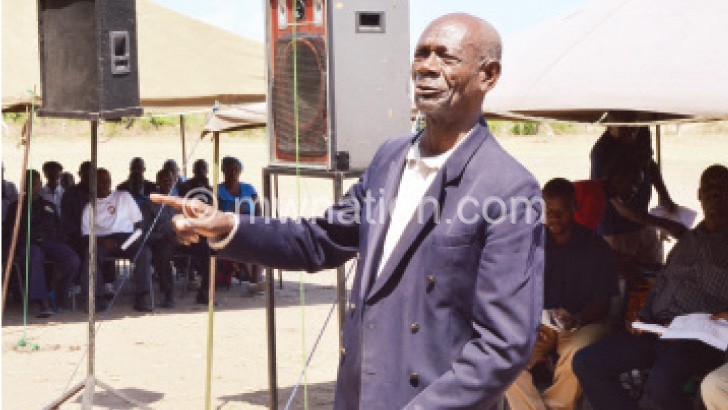

However, Mr One-Day has taken his approach to death to incredible limits by holding some sort of a funeral service in advance.

On a sunny day in December 2001, he invited his friends, relatives and spectators to the cassava-growing village to shower him with condolences—including eulogies, money, goats and chickens—while he still lives.

The gathering included Senior Chief Wasambo and other traditional leaders.

Group Village Head Mtawali remembered the K51 000 ceremony as “colourful, but someway shocking” as his friends carried his coffin from his home to the burial ground.

As Mr One-Day looked on, they placed the empty casket on top of his intended grave and the tokens of condolences started trickling in.

When asked about the one-off observance, Mr One-Day says: “I wanted to know my true friends. It is no use for people to contribute money and foodstuffs when one is dead. The dead do not need any of those things. It’s hypocrisy.”

He recalls the rite raised almost K30 000— “a lot of money” at that time”.

“My wife and I bought blankets, beds, clothes and other basics. In fact, I am still receiving vyamasozi (condolences). In the coffin is a book in which I record friends who have done their part.”

The dead man walking owes his name to the unique ceremony.

It all occurred in fulfilment of a boyhood dream he has harboured since his father’s death.

His father reportedly had a house and a herd of cattle, which are a symbol of wealth in his rural setting.

“When he died, his friends and relatives fled his house where his body was lying in state. One by one, they left. Some fanned their noses, saying his body was stinking. Quickly, elders agreed to put the coffin in the open and they rushed the funeral,” he recalls.

By the time of burial, the young Parodi, who was born miraculously on a dusty road as his mother was going to a distant clinic to give birth, was assured that “one’s house is not a permanent home”.

“We build expensive houses, but our home is in the graveyard. That’s where we will stay longer,” he says,

He remembers watching with grief as a crowd scrambled for food at the house of mourning.

Today, he perceives funerals as feasts except that the dead and the grief-stricken have no yearning for food.

“We must celebrate people while they are still alive. Show them love before they are dead. People should stop pretending to love you when you are dead. The dead don’t need money and meals,” he says.

His grave was captioned: “kuno nkhwamuyirayira”—an everlasting home. It comprised a five-seater hut, but he is expanding it to sit about 15 mourners.

For him, finding helping hands was not easy. He salutes bricklayer Bindira Msiska and six grave diggers who helped him build his final home.

At first, Msiska and friends needed convincing as they were wary of Gondwe’s intentions which are largely deemed as signs of madness or witchcraft.

At Uliwa Trading Centre, where he owns a hardware shop and houses for rent, some suspect this is part of a get-rich-quick ritual as he seldom wears shoes and long trousers.

By contrast, others know him as a workaholic who lifted himself from poverty single-handedly.

In 1995, he was repairing bicycles in the open. Today, he has a packed hardware shop, nine houses and two pickups for hire.

Mr One-Day clarifies: “I am Catholic and I work hard, except I am aware that I will die one day. I don’t want anyone to use my funeral to score points. Actually, I usually wear shorts and sandals because my legs are susceptible to high temperatures.”

Equally bothered about superstitious theories is his wife Mailess.

She says: “Some people tell me to leave him. I cannot fall sick without neighbours gossiping that my husband is bewitching me.”

She is admittedly accustomed to this—and the funeral plan was sanctioned by the family. They are happy it lessens the pressure funerals often exert on family income.

Every December, the man summons friends to remember his death.

Interestingly, the father of six says it is doing him a lot of good.

Mr One-Day says: “When I die, it is up to my people to hold a funeral or not. But the grave and the coffin are my biggest church. They teach me to live well with people.

“When I am angry, a mere sight of the coffin tells me to forgive. When poor travellers ask for a ride, I am happy to assist because we are all on the same journey. When we are dead, we will have to account for our works.” n

Odala awa Adzawayika maliro achitsiru.