Rich dominate higher education

They say education is the greatest equaliser—the only sure way of reducing the gap between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have-nots’—but as the latest World Bank study on Malawi’s education system and Nation on Sunday’s analysis show, education is, in fact, one of the main reasons the rich are getting richer while the poor are getting poorer. Senior News Analyst Ephraim Nyondo writes.

Higher education in Malawi is a preserve of the rich and the well-to-do, a 2016 World Bank study has revealed.

The study, titled ‘Improving Higher Education in Malawi for Competitiveness in the Global Economy’, shows that 91.3 percent of students enrolled in higher education are drawn from the richest quintile (20 percent) of households.

The poorest quintile of the households accounts for just 0.7 percent of higher education enrollment.

This means that the vast majority of university students in Malawi come from the wealthiest strata of the country’s 17.5 million people.

Such a socioeconomic profile of current University enrollment means that the wealthiest members of society disproportionately benefit from government’s subsidy to higher education in the form of budget allocations and student loans.

It also means that government is heavily subsidising a system which is benefiting the rich—something which is against the pro-poor policies as outlined in the country’s national development policies, for instance, the Vision 2020 and the Malawi Growth and Development Strategy (MGDS).

Experts, however, note that the concentration of relatively well-to-do students in the University population is a reflection of the disparities that manifest themselves in the education system starting at primary and secondary level.

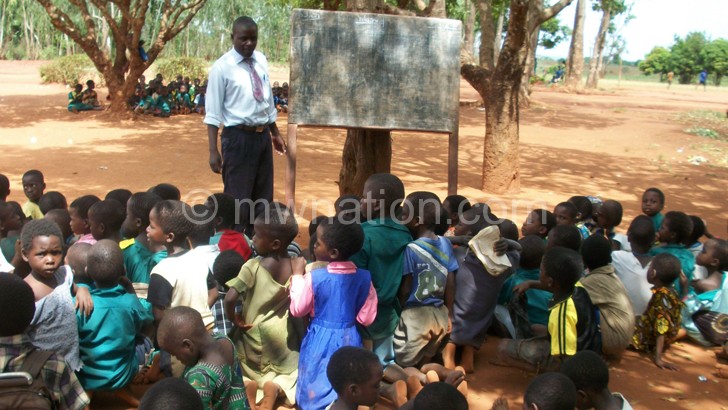

Educationists Limbani Nsapato says inequalities start from lower levels of life—especially early childhood education stage.

start as early as this stage

school block

He says less than 40 percent of children access nursery school or early childhood education, which is said to be the foundation for better learning outcomes.

The majority of those who have gone through nursery schools are from town and from rich families and these find their way to university because of strong foundation, he notes.

He further adds that one rarely finds children from very poor families, or children with disabilities or children from rural areas accessing nursery school.

The study further notes that while children from across the socioeconomic spectrum access primary education in relatively equal numbers, the performance of children from the fifth quintile diverge significantly at the primary level, with subsequent implications for access to secondary education.

It shows that 66 percent of children from the richest households (quintile 5) complete a full course of primary education compared to only 23 percent of children from the poorest 20 percent of households.

As a result, less than 10 percent of children from poor families enter lower and upper secondary education.

Children from the poorest quintile of households moreover demonstrate low completion rates of eight percent and two percent for lower and upper secondary education respectively, with further negative effects for the likelihood of their accessing higher education, adds the study.

The study also reveals relative inequity impacting the likelihood of a child’s educational survival is also reflected in the share of household expenditures allocated to education.

It shows that households from the first quintile spend on average 0.31 percent on education related expenses, compared to 0.9 percent in the fourth quintile and 2.84 percent in the fifth quintile.

These disparities, according to executive director for Civil Society Education Coalition (Csec) Benedicto Kondowe, form the strong basis of access to higher education in the country.

Kondowe and Nsapato, in separate interviews, argue for the need to have university selection system, especially in public universities, that is responsive to such disparities.

Currently, enrollment policy in public universities follow an “equitable access,” where each district contributes 10 students and the remaining space is shared according to a district’s geographic size.

However, Kondowe and Nsapato have faulted system, arguing it only perpetuates the problem of inequality in access to higher education.

In fact, even the National Council for Higher Education (Nche)—underlining that the country’s education system does not segregate learners or candidates based on socio-economic status—agrees that the equitable access policy does not provide mechanisms for supporting learners from poor economic backgrounds or learners from disadvantaged schools.

“Children from well-to-do families attend high quality schools and perform better compared to those from poorly resourced schools.

“Therefore, there is need for a policy on selection to recognise learners from poor economic backgrounds who attend poorly resourced schools,” said Mathilda Chithila, chief executive officer for Nche.

Such a policy, according to Kondowe, should include ranking secondary schools based on their availability of resources to supporting learning to objectively select students into the universities.

“For instance, students from the community day secondary schools will need special treatment if they demonstrate competence considering that they have very challenging conditions to teaching and learning,” he said.

So should ‘quota’ be abolished?

Nsapato thinks the ‘quota system’, while maintaining it as an affirmative action, should be reviewed to address all the inequalities arising from the various demographic factors, not just district as the only variable.

Chithila, however, feels the policy (equitable access) is relevant in terms of allowing access to places in higher education institutions to disadvantaged populations but obviously, like any policy, it needs to be reviewed from time to time to see if it is having the intended results.

“There are limited spaces in higher education institutions and there is need that merit must be complemented by another parameter to allow access to disadvantaged groups and this would include applicants from disadvantaged socio economic backgrounds and/or from disadvantaged schools,” said Chithila.

She underlined, though, that “as a council, we can only provide policy advice, but it is up to government to implement that advice because we are not the policy makers.”

Chithila further said Nche believes that the equitable access policy should deliberately address socio–economic issues apart from looking at disparities across districts and with respect to districts there is need to identify the reasons behind some districts doing better than others so that we address the cause, not the symptoms as is the case currently.

“That approach will also get rid of the perceived discrimination that is currently attached to equitable access,” she said