The search for God’s language

The dawn of multiparty democracy did not only change things on the political turf. It revolutionalised the religious and spiritual terrain among local churches, resulting in the birth of thousands of Pentecostal and Charismatic churches scrambling for the same 13-plus million people. What boggles one’s mind, though, is the tendency by preachers of Pentecostal and Charismatic churches to use English in a congregation that hardly has a member who speaks the language.

The dawn of multiparty democracy did not only change things on the political turf. It revolutionalised the religious and spiritual terrain among local churches, resulting in the birth of thousands of Pentecostal and Charismatic churches scrambling for the same 13-plus million people. What boggles one’s mind, though, is the tendency by preachers of Pentecostal and Charismatic churches to use English in a congregation that hardly has a member who speaks the language.

So why use English when a local language could do? WATIPASO MZUNGU Junior digs into the matter.

Lyness Saka, 79, a staunch CCAP member, is just one week old in Blantyre. She came from Mzimba to see her last-born son who is working for a company in the commercial city.

On her first Sunday in town, Saka asks for direction to a CCAP prayer house. She is, however, shocked to learn that there is none in the location where her son lives.

“The nearest CCAP prayer houses are Mpachika or St. Columba CCAP, which are about four kilometres away from here. You need a car to board a minibus for you to reach the church. Otherwise, I don’t think you can walk to the place at your age,” the daughter-in-law, AnyaPhiri, announces.

But Saka thinks it would be imprudent to spend her son’s hard-earned money on transport to church.

She, therefore, suggests that she be led to any church closer to the location.

“After all, God is one. God doesn’t care about where one congregates,” she argues.

A few metres away from the house lies Kapeni Demonstration School where some believers, especially from the Pentecostal fraternity, meet every Sunday for praise and worship.

At the doorstep into the classroom-turned-prayer-house, Saka is met by an usher and usherette who welcome her into the worship place.

“Takulandirani agogo [You’re welcome granny!]. You’ve made the right decision to worship with us for this is where Jesus is transforming people’s lives and deliver them from the bondage of sin,” an usherette announces as she leads the enthused granny to a seat.

As she tries to make herself comfortable, two youthful-looking men take to the pulpit with microphones in their hands.

“Please make yourself comfortable in the house of the Lord, alleluia!” says the man of God.

“Chonde, nonse khalani womasuka mu nyumba ya Ambuye, alleluia,” the other one translates.

Saka throws her eyes in all directions to see if there is anyone with a white skin in the church that would warrant the services of an interpreter, but she sees none. All in all, she remains patient to the last minute of the service.

“Mwana wane, pali na ichi natolapo ku tchalitchi kula! [My son, my congregating with that church has not benefitted me]. You see, there were two pastors in front of the congregation with each of them preaching in his own language. I couldn’t concentrate,” Saka tells her daughter-in-law immediately she arrives back home from the church.

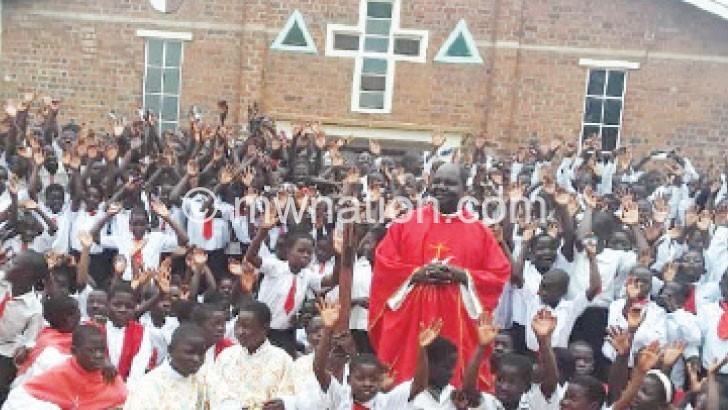

The dawn of multiparty democracy in 1992 also brought with it the birth of a myriad faith groups with most congregating in makeshift buildings such as classrooms, unoccupied shops and dwelling houses, among others.

However, what is surprising is that there is a great desire in almost all leaders of the new churches to deliver their sermons in the Queen’s language with an interpreter aside.

Incidentally, even congregants attempt to pray and worship in English while others try “tongues”.

At every corner of the building in cities nowadays, you will find a preacher and his interpreter. That is even if the lost souls he is ministering to are illiterate who would benefit more from a vernacular homily than the interpreted one.

What is interesting, though, is that early missionaries such as the White Fathers of the Catholic Church learned and preached in local languages to help members to understand the God’s plan for humankind irrespective of culture and language.

So, should it be difficult for locally-bred pastors to preach their own languages such as Chichewa, Tumbuka and Yao? Or is it that English has now become the official language for communicating with God?

“The only reason such pastors do this is to paint their lies true that the Holy Spirit makes them speak in other languages,” says Chancellor College-based Jehovah’s Witness, Gerry Leijen.

Leijen argues that what such pastors forget is that God created all the languages at the ‘Tower of Babel in Nimrods days.”

But social commentator Alex Nkosi sees nothing wrong in using English, arguing that by using this worldwide mode of communication, pastors are simply ensuring that no one is sidelined in the sharing of God’s word.

“God can hear any language and bless anyone who praises him wholeheartedly, but English is an international way of communication and we can’t change that. This allows everyone in the church listen to the word,” stresses Nkosi.

But a Blantyre-based journalist and social commentator, Ronald Mpaso, holds a different view altogether.

Mpaso says by preaching the gospel in English with someone interpreting, the non-English are simply trying to tell the world that their languages are inferior, which may not be the case as every language is superior in its own right.

“Are we trying to say our local languages are inferior? Does God not approve of them?” he wonders.

He says he, too, has come across scenarios where every member of a congregation speaks or understands local languages, but the preacher still clings to the Queen’s language, even where he appears not to be fluent in it.

“But there are some preachers who make recordings and send them abroad. In that case, the use of English becomes relevant. But generally, we look upon our local languages as being backward/inferior,” argues Mpaso.

Reverend MacDonald Sembereka of the Anglican Clergy believes that the culture of preaching in English originated from what he calls ‘Pentecostalism in Malawi’, which he argues emerged out of American evangelistic teams that invaded Africa to preach to people they believed were less evangelised.

“This has thus culminated in a culture of only those preaching in English being considered as good preachers that when you ask them to preach in the vernacular they will be uncomfortable,” says Sembereka.

He says the fact that God is omnipresent and, therefore, cannot be put in a language straightjacket.