When electricity goes rural

There is nothing painstaking in the first part of the journey from Mangochi Boma to Katuli, a remote village located at least 45 kilometres from the boma.

The beatific, smooth and tarmac Mangochi-Namwera-Ntaja-Liwonde Road makes travelling, though packed like sardines in a South African registered pick-up, quite illuminating.

As the road meanders up in the mountain chains, the view of the silent plains below is captivating, not to forget the splendor of gazing at the tip end of Lake Malawi giving in to the Shire River.

However, when you get meshed into the distant hills and disembark at Udubuli market to mark the beginning of the second part of the journey to Katuli, every beauty grinds to a halt.

You, now, begin to experience the reality of rural areas in Malawi. Public transport to Katuli is available, of course; but they are worn-out pick-ups that take, on average, four hours to fill-up. You do not have alternative but wait.

It is K1 000 for an hour’s journey from Udubuli market to Katuli, but if your pocket is brimming, you can hire a motorcycle and cough anything between K6 000 and K7 000.

The journey is painstaking: the road is narrow, dusty, and potholed and, sometimes, it snakes in deserted forests. You have an hour of enduring bumps, dust and numerous stops.

The feeling is that you are going to the middle of nowhere where life is predominantly rudimentary—no phone network, no electricity, no piped water, no modern buildings, etc.

But the feeling begins to fade away as Katuli, from a distance, begins to welcome you with a towering telecommunication transmitter. The closer you get, the more sophisticated Katuli becomes.

Vast mansions well-guarded by brick-walled compounds line along all sides of the dusty road leading to the main market. Shops are huge—and they, literally, sale anything: from groceries to clothes to electronics to hardware. Telecommunication network—for Airtel, TNM and MTL—is live and full. You do not need to stand on an anthill or climb a tree.

You would not be wrong to mistake Katuli market for Mbayani township market in Blantyre. It is busy, it is fast and it is noisy.

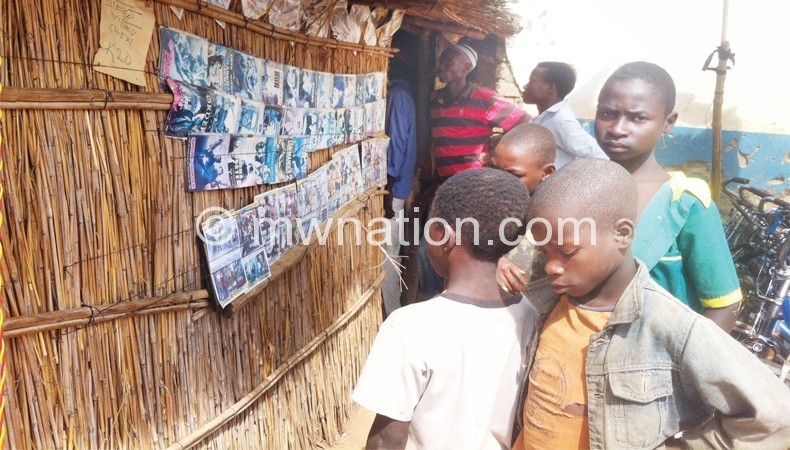

The noise from second-hand clothes vendors courting customers is wild. The wildness gets prickly when blasting sounds from electronic shops and video showrooms join the din. This is not to forget the vast sounds from panel beaters, motor-vehicle mechanics and moving vehicles and motorcycles.

The entire spectacle speaks completely the opposite of what defines a rural area in Malawi.

“Katuli has changed,” says Jonas Ajibu, 42, who runs a fast-food eatery where he sells chips and chicken prepared on an electric-powered stove.

Interviewing was a hustle because he had many customers to serve. To him, business is booming, lifestyles are changing, and everything about them is becoming modern, he adds.

“Our children these days are watching TVs. With a decoder, we are able to know what is happening everywhere in the world. We are no longer isolated. We are part of the world these days,” he says.

Ten years ago, Katuli was a small, rural trading centre without much activity. It was a typical rural trading centre which operates without electricity and everything goes to sleep with twilight. However, when electricity, under the Malawi Rural Electric Programme (Marep), came to the area, everything began to change.

Marep, which dates back to the 80s and is implemented in phases, is a long-standing initiative that aims at extending electricity grid to more isolated administrative and trading centres.

Currently at Phase 8—with access to modern electricity still at one percent in the rural area where 80 percent of Malawians live—the initiative is wholly owned by government and is administered by the Electricity Supply Corporation of Malawi (

), in terms of maintenance, operations and new connections. Government aims at increasing electricity access to 30 percent by 2030.

With hundreds of trading and administrative centres already electrified so far, the economic development that government envisions in Marep, though staggering, is, unarguably, bearing fruits—and Katuli is an example.

With small-scale businesses booming, Katuli has turned into a pull factor to surrounding villages. They come here to sell and buy and this is generating incomes which are being invested in automobiles and construction.

Ten years ago, Esmie Itika was, just like Ajibu, a subsistence sweet potato farmer. Being a widow, she had little to provide for her family. She was saving her money through the village savings loan (VSL) which she invested in airtime business and a phone-charging shop.

Today, she sells second-hand clothes. She has built a three-bedroom house which is electrified.

“I use electricity for everything; cooking, heating, ironing and entertainment. I no longer walk distances to fetch firewood,” she says.

But, as they say, every development comes with its own problems. For one, some children abscond school to watch films, especially foreign films translated into Chichewa.

“It is a major concern. You find children who should be in class at the video showrooms. This can be one of the factors that may lead to increased dropouts,” said Patuma Abasi, a mother of three, including two primary school-going boys.