Every water point counts

Muthi Nhlema has many passions. He is an engineer, a dramatist, a writer and a water-for-all campaigner. On the waterfront, he believes that keeping track of every water point is pivotal to achieving Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Six to ensure everyone drinks safe water.

“We need to scratch where it itches,” he says. “Unless we know the number, location and state of water points, the country runs the risk of putting resources where water points are not needed while communities without access are being left behind.”

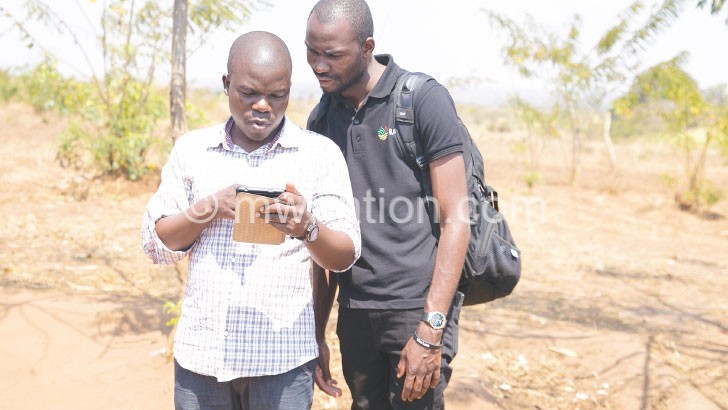

with a mobile phone data collection tool

Nhlema remembers experiencing a dramatic encounter when Water for People deployed him to Rumphi District in 2014 to locate and assess every water point.

“When we met the district water officer, he could only hazard a guess—maybe 950. But our team found over 3 300 on the ground when we went village by village. After sharing the experience with organisations working in Rumphi, they all said this news was not new.”

The government official, who lost count of over two thirds of water outlets in his district, personifies a familiar gap in all 28 districts in the country.

Even Google does not know the number and condition of water points in the country, for the worldwide web is stuffed with scanty anecdotes of what individual government agencies and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) are doing to improve access to water.

Government does not know either, says Water for People country director Kate Harawa.

“The experience in Rumphi only confirmed what we already know: data collection and management in government is not up to standard. Latest information is scarcely available nor accessible. This needs to improve,” she says.

In a fightback, bureaucrats also blame NGOs of sidestepping government officials when drilling boreholes to ease exclusion as a tenth of the population drink unsafe water.

Such are the blame games that anything from lack of ink in a printer to missing passwords is enough to deny policymakers, investors and change agents up-to-date information tey require to provide potable water where it is needed.

Boots on the ground

Since April last year, Nhlema and his team at BASEflow have hit the ground in a collaborative initiative called m-Water to map the type, location, condition and quality of water and sanitation infrastructure in the country.

His organisation has trained about 120 government extension officers, especially health surveillance assistants, to use mobile phones to pinpoint and put every water point on a virtual map everyone can use to make life-changing, water-wise decisions.

The mapping, which entered the second phase in May, is funded by the Scottish Government Climate Justice Fund Water Futures Programme.

It builds on previous attempts by Water Aid, Unicef, Africa Development Bank and other change agents.

“We have tried GIS, Excel spreadsheets and stacks of paper in government offices. m-Water is the new kid on the block. Using the phone application made in the US [United States] but modified to suit our needs, the government extension workers generate field reports that are validated and uploaded on a dashboard as soon as they arrive at our call centre in Blantyre,” says Nhlema.

So far, the enumerators have mapped almost 54 000 water points out of the “official best guess” of about 71 700 water points.

Beyond mapping

By 2015, Malawi had surpassed Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) to provide safe water to at least 75 percent of the population. The transition to SDGs call for greater investment, efficiency, accountability and equity to expand access to every person, especially a tenth of rural Malawians who are left behind.

“As we strive for SDG6, government views m-Water as an essential tool for mapping water points’ availability, functionality and potential risks of pollution. It’s also essential for planning and monitoring at both national and district levels,” said Zione Uka, the chief groundwater officer in the Department of Water Development.

Uka sits on a government task force steering the m-Water initiative.

“The data collected will be used to improve develop a dashboard for tracking progress towards SDG6 in Malawi,” she stated in a video screened at the World Water Week in Stockholm, Sweden early this month.

The m-Water initiative may be in its infancy, but geologist Alexandra Miller of the University of Strathclyde in Scotland, says it has the potential to become government’s preferred system going forward.

“We have so much data in Malawi, why isn’t mapping working? We are looking beyond mapping to management of water resources. Management information systems are essential for evaluating sustainable decisions for SDGs. In the country, government’s support is incredible,” she says.

A district at a time

The mapping also contains key information about domestic water systems, surface water, healthcare facilities, and schools.

Plans are underway to expand the m-Water user base across government, NGOs, investors and water users.

It has also aroused interest from local governments, with Chiradzulu District Council incorporating the count into its district investment plan.

Nhlema said: “We have begun with big districts and will end with smaller ones we can map in a day. In the end, we hope this will help improve accountability, maintenance, efficiency and access in the water sector.” n