Bank, analysts expose flaws in development

The World Bank has given an indictment on Malawi’s development strategies, saying the economic performance between 1995 and 2018 has failed to improve the welfare of its citizens.

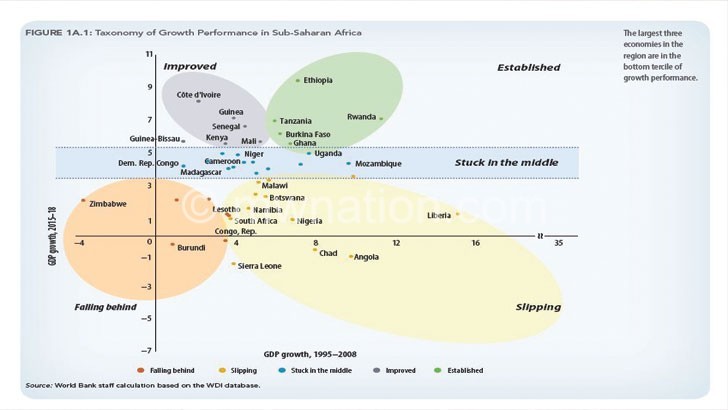

In its latest bi-annual publication called Africa’s Pulse released on Monday, the Bretton Woods institution says during the period, Malawi, alongside other 18 economies in the region, have seen their median or average economic growth rate decelerating from 5.4 percent per year in 1995 to 2008, to 1.2 percent per year between 2015 and 2018.

The World Bank has cited poor governance (corruption), low levels of per capita income and composition of public sector indebtedness as some of the key factors for the country’s poor economic performance coupled with sluggish economic growth.

The report by the World Bank comes at a time the country continues to be categorised in the low human development category of poor countries, ranked 171 out of 189 nations, according to the Human Development Index (HDI) of 2017.

While agreeing with the World Bank, former minister of Finance Friday Jumbe, in an interview on Tuesday, blamed the global lender itself for advancing economic reforms which he said later backfired on Malawi’s economy.

He cited the liberalisation of the economy, which he said on its own was a severe external shock to the country.

Said Jumbe: “My argument is purely economic, academic and professional. I agree with them that the economy has not performed well, but I don’t agree with them on the reasons they are giving for such underperformance.

“There were many economic reforms in Malawi imposed by the World Bank such as liberalisation, which created many economic problems.”

In 1981, Malawi embarked on a series of structural adjustment programmes, which entailed moving towards liberalising its price and marketing policies as advised by the World Bank.

In the first structural adjustment loans agreement approved in 1981, the World Bank recommended policy reforms which included price incentives and later privatisation of State-owned companies.

Since then, Malawi has experienced liberalisation of agricultural produce and input pricing; liberalisation of agricultural marketing services that opened up the activities to the private sector, including vendors who have flooded the agricultural markets, even in rural areas.

In its publication, the World Bank observes that the slower-than-expected overall growth for Malawi during the period reflects ongoing global uncertainty, but increasingly comes from domestic macroeconomic instability, including poorly managed debt, inflation and deficits; political and regulatory uncertainty and fragility that are having visible negative impacts on some African economies.

Malawi is grouped together with countries such as South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe. However, in the report, Tanzania has been rated highly having registered strong economic growth while Mozambique is said to have been stuck in the middle during the same period.

While the World Bank report is silent on the impact of Cashgate—the looting of public funds at Capital Hill exposed in 2013—many, including Finance Minister Goodall Gondwe, believe that such a plunder of taxpayers’ money will have long-lasting negative impact on the economy.

In recent years, Treasury finds itself in a tight corner to shore up expenditure in the national budget by balancing with available resources in the wake of continued withdrawal of direct budget support and dwindling grants since Cashgate was uncovered.

Previously, traditional donors provided about 40 percent support in the recurrent budget and about 80 percent in the development budget.

Donors have since changed their mode by preferring to re-channel their assistance through non-governmental organisations or what is called off-budget, in the case of development budget.

The World Bank report also found that fragility in some countries within sub-Saharan Africa is costing the countries over half a percentage point of growth per year.

“The drivers of fragility have evolved over time, and so too must the solutions. Countries have a real opportunity to move from fragility to opportunity by cooperating across borders to tackle instability, violence, and climate change,” said Cesar Calderon, lead economist and lead author of the report.

All this underperformance comes even as Malawi has executed various development strategies.

Since 1962, Malawi has had 11 development plans whose main goal was to grow the economy at an average of six percent. These include Nyasaland Development Plan (1962-65), Malawi Development Plan (1965-1969), Statement of Development Policies (Devpol I, 1971-1980), Devpol II (1987-1996), Poverty Alleviation Programme/Policy Framework Papers (1995-2000), Vision 2020 (1998-2020), Malawi Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (2002-2005), Malawi Economic Growth Strategy (2006-2011), Malawi Growth and Development Strategy (MGDS I), Economic Recovery Plan (2012-2014), MGDS II and now MGDS III.

The key question is whether these development strategies have helped to improve living standards of people or have worsened the situation.

Former Reserve Bank of Malawi (RBM) deputy governor (economics) Naomi Ngwira, who was also once director of debt and aid in the Ministry of Finance, Economic Planning and Development, earlier blamed the country’s state of underdevelopment on economists whom she said lacked collaboration in the area of research on economic development.

She said: “Progress has not been significant in the past 25 years. Where is the economy heading to? What has gone wrong? I know many people will blame politicians, but it goes beyond that and I think we economists as well are also to blame for not collaborating in research on the solutions and problems for Malawi.”

Economics Association of Malawi (Ecama) executive director Maleka Thula, on his part, said over the years, there have been different policy approaches and objectives with emphasis varying from economic growth and poverty reduction, but they seem not to have worked.

“Thus even with growth registered so far, trickle-down effects have been insignificant on the majority of the Malawians,” he said, blaming weak policy implementation by successive governments.

Thula said there have been times when policies being implemented have been pro-poor, adding that ‘the stop-go’ kind of policy implementation has resulted into failure of pro-poor policies to have sustained and meaningful impacts on poverty reduction.