Civil service bloats by 61%

The size of Malawi’s civil service surged 61 percent between 2008 and 2015, raising fears about the sustainability of the wage bill and its impact on public service delivery.

A special analysis by the World Bank in its Malawi Economic Monitor report on how much Capital Hill is spending on the public sector wage bill, says the number of public servants has grown from around 110 000 to 178 000 over the past seven years.

That figure is expected to reach 186 000 in 2016, which is an additional 4.5 percent that Treasury spokesperson Nations Msowoya said on Monday was planned for hiring between January and June 2016—the second half of the current fiscal calendar.

The quoted numbers are just for the core civil service; thus exclude parastatals, said Msowoya.

The growth in staffing levels, according to Treasury, has mostly come from sectors of education, especially recruitment of teachers; health to boost numbers of nurses and doctors; agriculture to broaden and deepen extension services and police to improve security.

But the World Bank and some economists say the increase is alarming and have since called for a recruitment freeze and reduction in the staffing levels that are bleeding the economy and the national budget.

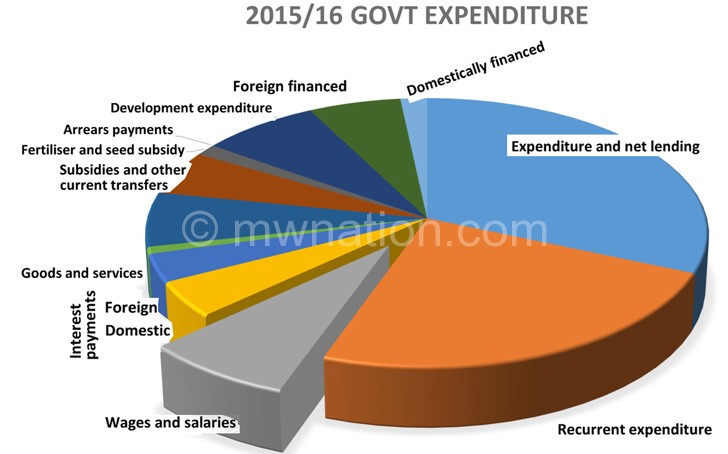

The total value of the public sector wage bill reached a peak of the equivalent of 9.9 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in the 2014/15 fiscal year and now accounts for around a third of recurrent expenditure of the budget.

As a ratio of the whole national budget—comprising both development and recurrent accounts—The Nation’s calculations show that the wage bill represents roughly 21 percent of total planned expenditure; but Treasury says the ideal is for the percentage not to exceed 10 percent; meaning the current ones are double the norm.

The fraction of the recurrent budget pie that goes to personal emoluments is several times those of health, governance institutions, infrastructure development, education and agriculture, irrigation and water development.

And that is at the crux of the experts’ worries, including the World Bank.

“With such a large share of government expenditure allocated [to] wages and salaries, this leaves limited space for non-wage expenditure on items such as teaching materials in schools, medicines in hospitals and health centres or the maintenance of existing capital investments,” it says.

That is also the concern of the Economics Association of Malawi (Ecama) president Henry Kachaje, who on Monday said a public service that is almost 10 percent of GDP exerts enormous pressure on government expenditure, especially at this time when there are already fiscal slippages and under-collection of domestic revenues.

“It will be unfortunate if we retain a bloated civil service wage bill while failing to have the public service deliver services in education and health, for example, simply because there is very little money left for purchase of goods and services needed in the public institutions like hospitals and schools,” said Kachaje.

And economic governance expert at the Centre for Social Concern (CfSC), Mathias Kafumba, said in a separate interview on Monday that additional wage pressure is likely to have adverse effects on government’s investment pattern, thereby impacting negatively on development projects that are crucial to spurring economic growth.

Both Kafumba and Kachaje worry that the ongoing public service reforms seem not to be working as the numbers of workers are increasing when they should have been falling on the back of staff rationalisation, chucking out of ghost workers and streamlining the burgeoned payroll and make the public sector more efficient and effective.

When contacted yesterday to explain the mismatch between the ongoing reforms—that, among other objectives, should result in a leaner and more efficient civil service—and the ballooning payroll, Principal Secretary for Public Sector Reforms Management Unit, Nwazi Nthambala, said he could not respond as he was on leave.

For Kafumba, a hiring freeze and staff lay-offs should be enforced not just to reduce the size of the workforce and save money, but also to improve the efficiency and quality of the public sector.

But freezing hiring—let alone cutting staff numbers—are a tricky affair, especially in sectors such as health and agriculture where there are already huge gaps.

In the education sector, for example, says Civil Society Education Coalition (Cisec) executive director Benedicto Kondowe, the country has a primary teacher shortage of between 40 000 and 45 000. In secondary schools, the gap is between 12 000 and 15 000 teachers.

But where does government get the money to recruit so many when, already, 81 percent of public spending on education in Malawi is—according to the World Bank report—on teacher salaries, yet outcomes remain embarrassingly low?

There is no doubt that sharp hikes in the public sector wage bill—mostly a result of civil servants blackmailing Capital Hill through strikes or threats of industrial action—have contributed to the current fiscal pressures and macroeconomic instability the country is limping through. How then does Treasury restore the necessary balance?

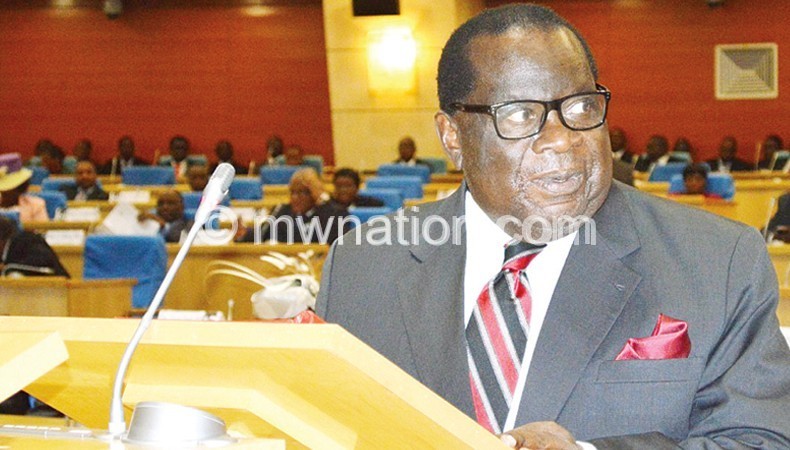

These are issues that Finance, Economic Planning and Development Minister Goodall Gondwe signalled he is grappling with in his 2015/16 budget statement even as he announced salary raises and a recruitment drive of 10 500 primary school teachers and 466 secondary school teachers who were projected to join the civil service around this time.

Said Gondwe in his 2015/16 budget statement: “These initiatives as well as an annual wage creep scheduled for implementation in December 2016 will raise the wage bill from K198.0 billion in financial year 2014/15 to an estimated K228.7 billion.”