Cookstoves for healthy forests

For years, group village head Pongwe of Zomba has seen people planting trees but the numbers growing remain “far below those cut down for cooking”.

From his rural territory under Senior Chief Chikowi, he sees whirlwind whistling in bare hills and fields once draped with natural forests. The trees that took decades to grow big needed just a few minutes for menacing axes to chop them down.

“As government and its partners lead the annual tree planting season, most of them go up in smoke because nearly every home cooks using firewood or charcoal,” says Pongwe.

Community Energy Malawi (CEM) distributed 400 efficient cookstoves, called Chitetezo, to low-income, firewood-consuming households in Pongwe and the neighbouring Mkata Village under the Phikani Moganizira Chilengedwe project.

Under the clean cooking initiative funded by Japan through the United Nations Development Programme, some 2 700 households in Zomba and Lilongwe will access Chitetezo cookstoves and gas cookers.

As trees vanish, women endure lengthening trips to fetch firewood.

Users say the handmade cookstove reduces the burden as it uses more than half the firewood consumed in traditional three-stone fireplaces.

Edna Chimbalanga, from Zomba where most mountains lie bare, is happy that her family now helps save trees.

“Chitetezo burns just three or four sticks per meal, meaning we are spending less money on firewood and a bundle that took a week in open fires now lasts two weeks. It also uses sticks and crop residues, reducing the frequent long walks to fetch firewood,” she explains.

Chimbalanga is excited that her Chitetezo mbaula emits less smoke and toxic fumes that irritate her eyes, nose and throat when cooking.

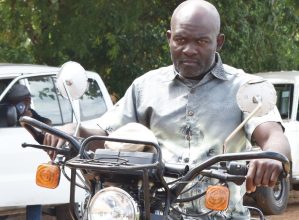

Pongwe sees increased access and use of the cookstove lessening population pressure on forests under siege from axe-brandishing charcoal producers and firewood hunters.

As natural forests have almost disappeared, the rapidly growing population is turning to mango trees that gifted them succulent seasonal fruits during the lean seasons from October to April.

“Simple tools like Chitetezo can save trees. Population growth means more hands scrambling for shrinking forests,” says village head Mkata.

He wishes every household uses the cookstove.

“This would mean fewer raids on the depleted forests, few trees burning in open fires, few crop fields losing fertile topsoil to racing rainwater in treeless slopes and few worries about erratic rains that worsen hunger and poverty,” he explains.

Chitetezo cookstove is part of Malawi’s toolbox for tackling deforestation, environmental degradation and global warming. The national anti-charcoal strategy promotes the cookstove in a mix of solutions, including liquid petroleum gas, briquettes and licensed charcoal produced from sustainably replenished plantations.

However, charcoal remains widely produced and openly on sale nationwide.

The project ramps up the ambitious national push to put five million energy-efficient cookstoves in use by 2030, the deadline for the global Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) to end all forms of poverty, including energy gaps. SDG7 is a call to “ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all”.

According to the 2018 census, just about 12 percent of Malawians access grid power and only one percent of them use electricity for cooking, with more than nine in 10 households using firewood and charcoal.

Malawi has consequently lost nearly half of its forests in four decades, reports the Forestry Department under the US-funded Malawi Clean Cooking for Healthy Forests project. This loss represents an equivalent of 30 000 hectares a year, one of the worst deforestation rates in southern Africa.

The cookstove can help disrupt unsustainable cooking practices that have depleted the forest cover of Zomba Plateau and “nearly every other hill in sight”, according to CEM district project officer Inviolata Laviwa.

“We need technologies people can use to save forests and their health, but firewood and charcoal use remains widespread since electricity is either inaccessible or not reliable,” she explains.

CEM also distributed cookstoves in the populous Mtandire and Mtsiriza townships in Lilongwe. The clean cooking initiative includes installations that turn food residues and human waste into biogas for cooking meals for inmates at Mikuyu Prison and patients at Zomba Central Hospital’s guardian shelter. Such crowded facilities consume truckloads of firewood from the shrinking forests every month.

“It’s a pity the trees are gone and rains increasingly wash away fertile soils from crop fields into streams, leaving harvests dwindling and the country prone to flooding as hunger and poverty bite harder,” Laviwa explains.

She expects the cookstoves, biogas, LPG to make lives better and forest healthy.

She recalls: “Seeing Mkata and Pongwe villagers scrambling for the cookstoves, I wished the technology could reach more people to protect not only the environment but also human health.

“The cookstoves burn few pieces that emit less toxic fumes, cutting the risk of women and children dying from preventable diseases while doing an everyday activity, cooking.”

Trees also cool the planet and refresh the air animals, including humans, breathe.

Mkata implores the current generation to save forests for its well-being and generations to come.

He reasons: “We need to plant more trees and faster than we are felling them.

“Since we are not, we have to slow down the depletion of forests because our children and their children may find none for cooking or halting soil erosion. Think about barren crop fields, bad air and erratic rain—hunger, diseases and poverty will get worse.