Dark side of solar energy

Off-grid products are creating waste in Africa and the burgeoning solar sector has a responsibility to consider the afterlives of its products, writes science .

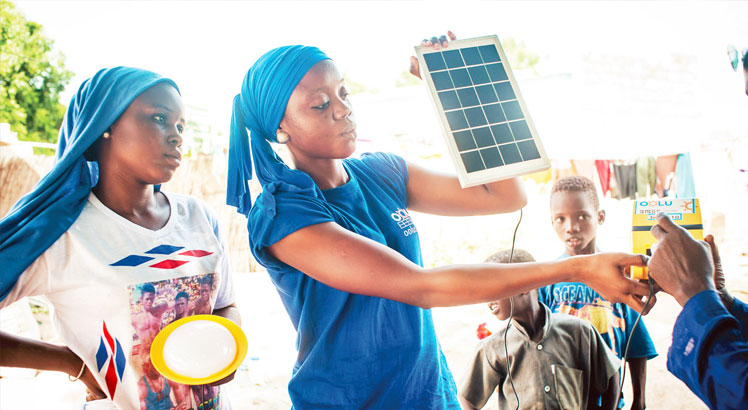

Household solar products are improving the quality of life for people living in developing nations, but many off-grid solutions last less than four years.

When they fall into disrepair, they worsen the growing problem of solar e-waste.

This brings the sector’s green credentials into question, says Scientia Associate Professor Paul Munro from the University of New South Wales (UNSW) School of Humanities & Languages in Australia.

Explains the energy poverty expert: “Over the past decade, there has been a boom in the sale of off-grid solar products. Around 200 000 products were sold in 2010.

“By 2019, that had increased to more than 40 million products worth around $1.75 billion in sales. This has helped many energy-poor homes and businesses in Africa get access to electricity.”

Solar lanterns and fans are replacing kerosene and battery-powered alternatives, which are both toxic and costly, while household solar systems power lighting, charge mobile phones and run bigger appliances such as televisions.

This explosion of renewable energy enables new opportunities.

One man in rural Malawi said: “My kids are able to study during the night and the things that I thought impossible are now a thing of the past.”

However, it has worsened solar e-waste with regulatory frameworks unable to keep pace.

“The sector has a responsibility to its customers and to the planet to consider products’ afterlives,” says Munro.

Sustainable Development Goal seven on universal access to affordable, reliable modern energy is considered a high priority because it is intersectional impact.

“You need energy to improve health and education outcomes to operate medical technology to save lives and enable reading in schools, access to computers to facilitate learning. So, energy is often seen as central to reducing inequities, enabling greater opportunities and meeting diverse goals.”

Last year, Munro’s fieldwork in Ghana revealed that almost every household in off-grid areas owned several solar products, but probably 95 percent of these products were not being formally sold by recognised off-grid solar companies.”

The quality of both branded and informally traded solar products varies considerably, he reports.

“Most only last three to four years before breaking down. Some only last a few months. Even branded products only tend to have one to two year warranties,” he says.

The complex trade networks and consumption patterns in Africa present substantial barriers to addressing solar e-waste, the researcher states.

Solar e-waste negatively impacts local communities as waste and landfill sites, commonly located close to poorer communities, come with a financial burden and hazardous materials that leak into the soil, affecting agriculture and water sources.

“As such, neglecting solar e-waste undermines other Sustainable Development Goals [SDG] nine on inequality [SDG9] and responsible consumption [SDG12],” he says. “Supporting local repair economies and design-based practices of repair can help ameliorate the issue.”

Munro researches political ecology and energy justice, exploring how emerging technologies can help combat energy poverty in developing nations, including Malawi, Ghana, Uganda, Kenya and Vanuatu.

The formal off-grid solar industry has attracted more than $2 billion in investment since 2010, mainly from investors in the US and North America.

Ironically, however, it is the informal off-grid solar sector that has been the most effective in distributing and installing solar products through local trade economies.

Most families cannot afford an all-in-one household solar system or to hire a certified installer, says research partner Dr Shanil Samarakoon from UNSW Engineering.

She states: “In Malawi, for example, what we’re finding is that households are often learning as they go along in terms of how to actually construct these systems

“… it’s a process of trial and error and a matter of buying these components as and when they can afford it. So what we see as we are visiting these households is often really DIY jobs in terms of installation.”

To date, many solutions to solar e-waste have focused on recycling over repair and design innovations, Munro says.

“But recycling relies on expensive infrastructure and it largely ignores the value of locally coordinated cultures and local repairers’ organic responses to the solar e-waste issue,” he warns.

While the need for greater repairability is recognised and openly discussed, each country has different capacities, distribution patterns and legislation. This makes it hard to formulate a broad geographical response, he says