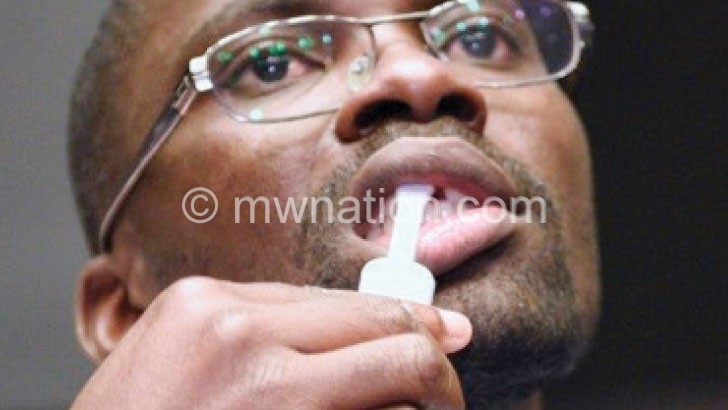

Fighting HIV the oral way

For Fanuel Master, the thought of taking an HIV test was frightening. It scared the hell out of him that a medical practitioner would know his HIV status.

But in an instant, it all changed.

The 24-year-old bicycle taxi operator at Dyeratu in Chikwawa recently took his first HIV test using an oral self-test kit at a science fair Malawi-Liverpool Wellcome Trust (MLWT) organised to expose people like him to the HIV testing innovation.

It was liberating and empowering for Master and his kind.

“I am happy that now I know my HIV status without anyone else knowing the results. I feel that this approach will appeal to many people here because many are afraid of being humiliated when somebody has access to their results,” said a relieved Master.

Early HIV diagnosis enhances access to anti-retroviral treatment (ART) and survival prospects for people living with the virus which causes Aids.

This is central to the United Nations (UN) 90-90-90 idea that by 2020, 90 percent of people who are HIV infected will be diagnosed, 90 percent of people who are diagnosed will be on ART and 90 percent of those on treatment have suppressed viral load.

Innovations like self-testing come in handy to fill the gaps in conventional HIV testing.

Epidemiologist Augustine Choko, MLWT lead research fellow in HIV, says the self-test approach offers an important window for expanding tools for fighting HIV and Aids.

He says: “In 2010, we did our very first HIV self-testing study in Ndirande and Mbayani in Blantyre. The research showed that out of 100 people, 92 accepted to take up the offer. The results also showed that with very minimal training people were able to conduct their own testing.

“In other words, if you told them and showed them how to do the test, people were able to do the test and read the results. They recorded the results and went back to a trained counsellor who would read the results.”

According to Choko, almost all the participants in the study successfully conducted the process on their own.

He explains: “Also, the counsellor would do the blood-based test and we were able to compare whether the oral test worked well versus the blood test. We found out that out of 100 people, 99 performed their testing correctly.

“So as a larger study, the first pilot involved 250 to 300 people, we did another one in the same communities, Ndirande, Likhubula and Chilomoni, where a neighbour offered access to the test kits. Nearly all youngsters came forward to have this, so it appealed to the youth who are often looked at in a very stigmatising way when they go for HIV test.”

Based on the 2017 HIV Prevention and Management Act, the youth aged 13 and above do not need parental consent to go for an HIV test.

But Choko says this has not stopped people’s tongues wagging when they see a very young person going for an HIV test.

“The results also showed that nearly all women available in those communities took up the offer and nearly 98 percent of the young men between 16-19 years did. There was a high uptake among men; 67% of all men tested when we made this available in the communities,

“You know, the most important thing that appeals to men is that it’s very convenient, they don’t need to make a special trip to the hospital or to a testing site to have an HIV test.”

Such interventions ensure people diagnosed with HIV start treatment on time. Nine in every 100 people in Malawi are HIV positive.

While nearly 75 percent of the 1.2 million HIV-infected people in the country get care, voluntary testing scales up the uptake of treatment and the broader war against Aids.

Self-testing could help overcome widespread stigma preventing some people living with HIV from knowing their status.

Oral testing, therefore, gives people the ease to self-test in the safety and privacy of their homes.

“What we have learned so far through the journey is that HIV self-testing is highly acceptable; it appeals to people and answers most of the questions that we have with conventional testing. People are afraid to show up at a testing site because of stigma,” says Choko.

It also eliminates the costs one endures to make a trip to an HIV testing and counselling centre, where the client’s privacy or desire to be the first to know the results may not be guaranteed.

“When you go to the testing site and give a blood sample for a test, sometimes you hear stories that these samples have been mixed up and the results that you receive are not really your own. In this case, this [oral testing] is empowering because it gives you confidence that you have done the testing yourself,” says the researcher.

He says they did not see any adverse events in a trial in which pregnant women received self-testing kits to pass on to their male partners.

“We saw a very high uptake of up to 95 percent of the male partners. The women said they had self-tested, which was really encouraging,” says Choko.

There were fears that self-testing would result in people committing suicide upon discovering that they are HIV-positive, but the trials allays this.

Says Choko: “We have done over 100 000 self-tests and I have not heard anything like that. Around the world, people are now looking to add self-test to the conventional interventions to reach people who don’t come forward at testing sites.”