Flood victims embrace winter cropping

A round this time last year, the family of six was among hundreds of Malawians displaced by chronic floods in the shoreline district of Karonga.

Group Village Headman Mwakyusa in Traditional Authority (T/A) Kilupula sombrely remembers heavy rains that poured for weeks in February when North Rukuru River broke its banks, reducing his home to rubble and washing away nearly two hectares of rice.

“Everything was washed away,” says the traditional leader who spent weeks in an overcrowded camp.

In October, Mwakyusa was among affected households which received emergency food supplies that Telekom Networks Malawi (TNM), Old Mutual and Huawei in partnership with Malawi Red Cross Society (MRCS) distributed to alleviate the suffering of the flood survivors.

He speaks of eight months of untold hunger and poverty, saying: “That was the first time nearly 200 affected households received 50 kilogrammes of maize each.”

MRCS intervened following an SOS from Karonga District Disaster Management Office in reaction to the plight of the population whose crop fields were swamped and washed away in Kilupula and Mwakaboko.

In the last growing season, the devastating floods left 6 624 households faced by food insecurity having destroyed nearly 505 hectares of crops, especially maize, cassava and rice, in Karonga. Maize alone accounts for 494.6 hectares.

Despite this perennial tragedy, Mwakyusa villagers have stayed put in the flood-prone zones.

“We are used to this land. The soils are good for crops and our ancestors are buried here,” says the village head.

But this may as well be about protecting his territory, headship and the nyakyusa way of life.

He cannot imagine his people mixing with other tribes in a new setting where his authority is not guaranteed.

In their risky zones, Austin Mwamlima from Paramount Chief Kyungu area is struggling to feed his family of five.

The man, who took refuge at Chinsebe Primary School for five months when the torrent shattered homes and displaced hundreds in Kyungu, lost almost everything. His maize fields were swamped for almost two months.

“We were at the camp from February to June. We harvested almost nothing because farming was almost impossible when disaster struck,’’ he says.

The flood plains in Kyungu’s territory were the worst hit by the catastrophe, losing nearly 460 hectares of crops out of estimated 503.6 hectares.

Interestingly, Mwamlima has harvested close to 20 bags of maize weighting 50kg each-thanks to irrigation farming spearheaded by the CCAP Synod of Livingstonia.

His household was among 700 flood victims who received farm inputs—three kilogrammes maize seed and two bags of fertilizer-for winter cropping.

Located near North Rukuru, his one and a half hectare garden comprised a health crop since July when he replanted.

“Having endured this food crisis for months, I am optimistic that my family will have something to eat until the next harvest in March,” he says.

The synod is implementing the four-month recovery project with funding from Tear Fund of the United Kingdom (UK).

Project coordinator Waluza Munthali expects the intervention to lessen hunger and poverty in the area.

But he is happy that it has also helped to change people’s mindset from overreliance on handouts to self-assistance.

“Organisations usually donate food items to flood victims, but the supplies are not long-lasting. They are not sustainable as each household get just a tin of maize or two,” he says.

Supporting the farmers with farm inputs has led to high yields and it is instilling in the community a sense of playing a part to change their prospects whenever tragedy strikes.

Most of the affected areas in the lakeshore district are situated near waterways, making them ideal for irrigation and winter cropping.

Desk Officer for district disaster management office, Franklin Mtambo, says provision of food items for flood victims is costly and hardly attainable.

“Even with support from various partners, most of the time we fail to assist all affected with foodstuff. Irrigation farming is the most resilient way. Handouts are not sustainable,” he says.

Weather forecasts show a likelihood of floods in the district which sometimes gets flooded with run-offs descending an array of hills in Chitipa.

Out of 334 900 hectares of farm land in Karonga, about 12 000 hectares is irrigable. However, nearly half of this land lies idle as rivers flow to the lake throughout the dry seasons.

Karonga Agricultural Development Division (ADD) programme manager Wellington Phewa says the district is moving in the right direction in ensuring that farmers are cultivating more than two times per year.

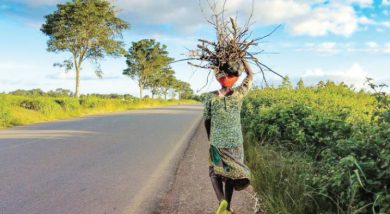

However, he lamented massive deforestation and siltation of major rivers used for irrigation as major drawbacks.

“The reduced water flow is affecting a number of irrigation schemes in Karonga,” he says. n