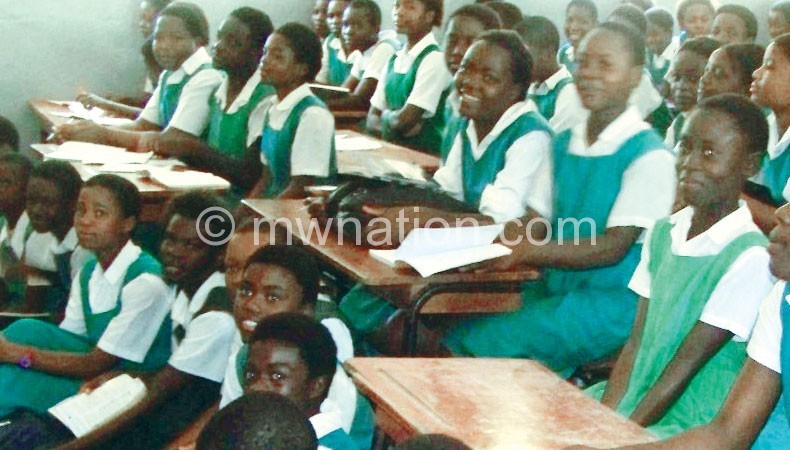

Girls’ education: Engine of rural development

Despite sporadic yet enviable rural development strides championed by the combined effort of NGOs and communities, most rural areas in Malawi continue to wow in poverty. Analysts and researchers, however, appear to agree that unless Malawi, or Africa, invests in girl’s education, the journey to development will remain slow. I explore the argument in the fourth part of rural integrated development series.

——————————

It is difficult, especially in the remotest and impoverished villages of Malawi, to become a teacher at a primary school you learnt when you were a child.

In fact, it is even more difficult if you are a woman.

But for 24-four year-old Lucy Jamison—a standard five teacher at Navuwu Primary School in the remote of Traditional Authority (T/A) Mwanzama in Nkhotakota—the story is almost a joke. She is a qualified teacher at a primary school she learnt while although with painful memories.

“Just in our village, I had 14 friends, all of them girls, who we started school together. I am the only one who did not drop out of school. The last of my friends to get married was Elube. She got married while in standard six. The rest got married even before that,” she says.

Her family was not anywhere near rich in the village. What with the father, a fisherman, and the mother, a housewife? Her father’s fish proceeds, recalls Lucy, could not even meet the basic needs of a family with eight children.

However, despite that, her parents, inspired by a neighbour who was a teacher at Navuwu, encouraged the little Lucy to stay the education course. They resisted every force to marry their girl, just like it is common here, to any man. Their hope was that Lucy would, one day, be their redemption.

“When I passed the Primary School Leaving Certificate Examination (PSLCE), I got selected to Nkhotakota Secondary School. After that, I went to a Teachers Training College and came back to my village as a teacher,” she says.

By modern capitalist standards, Lucy may not be rich: she is married, has a daughter, lives in a three-bedroomed house and she hardly depends on her husband for anything. However, by the standards of her impoverished village, she is the model of progress.

“Right now, I am building an iron-corrugated house for my parents. I want them to appreciate what they stood for by resisting getting me married at an early age,” she says.

Today, Lucy is the enviable model of most girls in her village. One of such girls is Mary Natho. Mary, a second-born daughter of a fisherman with seven other children to look after, was impregnated while in standard six when she was only 13. Today, at 14, she has a baby girl but unfortunately the boyfriend responsible, who promised marriage, refused taking it.

“Right now, I am just staying at my parents’ home. I have to struggle for my child to eat and dress,” she says.

So at 14, where, in her lakeshore village known for sex and fish, would Mary get the means of feeding and clothing her child?

Unfortunately there are many Malawian girls who end up with Mary’s tragic story. They are poor, uneducated, economically disempowered and, above all, unskillful to venture into a business of their own.

Had Lucy stayed in school beyond standard eight, there would have been many benefits not just to her but also for the nation at large.

In recent years, these experts and activists have come to quite a provoking conclusion: if you want to change the world, invest in girls.

There is a big reason for that. Across Malawi, by the time a girl is12, she is tending her parent’s house, cooking and cleaning. She eats what is left after the men and boys have eaten; she is less likely to be vaccinated, to see a doctor, to attend school up to secondary school.

For instance, the 2010 Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) show that less than one in five girls make it to secondary school. Nearly half are married by the time they are 18; one in seven across the country marries before she is 15.

Then, like Mary, she gets pregnant at 13.

The leading cause of death for girls aged between 15 and 19 is not accident or violence or disease; it is complications from pregnancy. Girls under 15 are up to five times as likely to die while having children than are women in their 20s and their babies are more likely to die as well.

As such, there are countless reasons rescuing girls is just right thing to do if the country is to fight poverty in the rural areas.

Consider the virtuous cycle: An extra year of primary school boosts girls’ eventual wages by 10 percent to 20 percent. An extra year of secondary school adds 15 percent to 25 percent.

Girls who stay in school for seven or more years typically marry four years later and have two fewer children than girls who drop out. Fewer dependents per worker allows for greater economic growth.

The World Food Programme (WFP) in 2010 found that when girls and women earn income, they reinvest 90 percent of it in their families. They buy books, medicine and mosquito nets.

“Investment in girls’ education may well be the highest-return investment available in the developing world,” Larry Summers wrote when he was chief economist at the World Bank.

But investing in girls’ education, though being heavily supported by NGOs, remains one of the greatest challenges in terms of designing and implementing a viable project that would capture the vulnerable girls and get them back to their right development framework of change.

Take for instance the story of Joyce Mbilika, nine, a rural girl from Pende village, GVH Fombe, T/A Mlilima, Chikhwawa.

“I want to become a nurse; I love the way they dress, I love tending to the sick,” she says while writing her name on the ground, as others cheer on.

Joyce, just like Lucy and Mary from Nkhotakota, comes from a village that asks questions that reveals the odds against girls: Why educate a daughter who will end up working for her in-laws rather than a son who will support you?

And it doesn’t end with such question, says group Village Headman Fombe.

“Here, married men take advantage of young girls who live with helpless widows. They help the widow on condition that they sleep with the girls. Sadly, most of these girls become pregnant and dropout of school,” he says.

Yet that is not all.

“We have some fathers who give their young girls to rich men in exchange for gifts. They either marry them off, or sometimes just let the rich men do whatever they want with these girls,” he continues.

If Joyce is to grow up and realise her dream like Lucy, she will have to revolt against her society. But she is only a girl, a complete minor. Can she?

Centre for Alternatives for Victimised Women and Children (Cawvoc) is one NGO implementing a project in Joyce’s area to help girls live to their aspirations. They invest in removing hurdles society imposes on these young girls.

“Our approach is dialogue with the community. We are talking with the communities, raising awareness on the need to protect the girl child, to help remove the hurdles that militate against their progress,” says Joyce Phekani, the Cawvoc’s executive director.

To achieve that, Cawvoc set up committees in the village to police the welfare of girls. They comprise both men and women. John Chilima is a member of one of the committees.

“We visit different households where we share with them the importance of educating girls. Whenever something bad happens or is about to happen to a girl, locals report to us. We talk with perpetrators, when that fails we report to the village headman. If that fails to achieve the intended goal, we take the matter to police,” says Chilima. Such committees are spread across the village and their work is similar.

“We want these young girls to get educated, support their families and develop the nation. We are investing in interventions that will remove the hurdles,” continues Phekani.

However, beyond interventions championed by NGOs, Lucy feels that government or non-governmental organisations should use models to help girls to stay in school so that they become forces of rural development.

“The challenge I faced head on—something that made to go to college—was that we did not have people to look to, people we should admire, people we should get inspired from. I grew up without knowing the value of education.

“Today, I know how a girl’s education can change Malawi. We need people like me across the country to spread the fire of change,” says Lucy.