Learning in tents the Chingoli way

About half a kilometre from Nkando Trading Centre in Mulanje, woes of compromised education standards and hardships at Chingoliprimary school are glowing. Since the January floods that washed away some school blocks and rendered others unusable, the term ‘quality education’ has been out of the equation.

Head teacher at the school puts it bluntly: “The situation is discouraging. If we are to define quality education by its acceptable conditions, no teacher or pupil is enjoying business.”

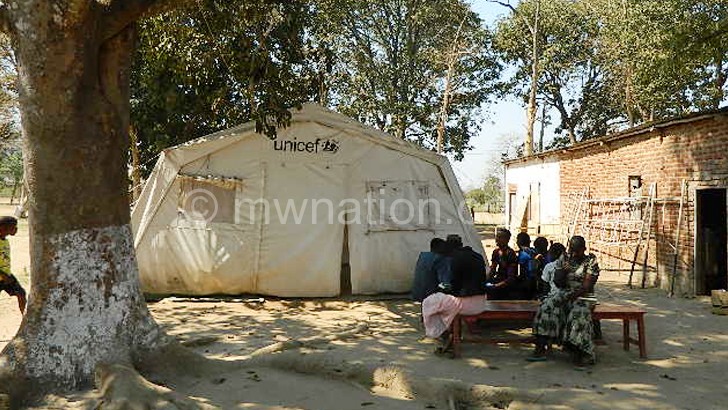

There is almost a new school with its structures planted just metres away from the original location. Unlike the old school which was built with bricks, the new Chingoli Primary School is defined by classrooms made of tents.

“The floods destroyed almost every structure of the old school. Some blocks that did not collapse have cracks and are unusable. For school to resume, Unicef came to our rescue and erected tents to be used as classes,” explains Chiromo.

There are nine tents and these accommodate Standard One to Standard Eight pupils. The other is for administration. During our visit towards the end of last term, we got business as normal. While the tents serve as a relief to the community as they have ensured access to education is not disrupted, the conditions and standards of education are seen as a litmus test.

The classrooms are not conducive for learning. The tents have poor ventilation and lighting. They have no windows, but just some small openings for aeration and translucent sections that ensures there is lighting inside.

“It is worse when it is cold because you cannot say you have closed all the openings to stop cold air from getting in. It is very cold and not conducive to stay for longer hours. Even when it is hot, the openings for ventilation are too small,” laments one pupil.

It is hell in the junior classes where there are no desks. The classrooms have dusty floors. Girls are forced to sit with their legs straight while boys sit on pieces of bricks.

Another pupil complains of frequently working on the floor smearing mud to make the floor harder thereby reducing dust. “That, however, is short-lived since the classes have many learners and trampling on the floor brings the dust back,” he adds.

This has brought another complication, as attests one Standard Four girl: “I have to wash my uniform every day after school unlike the past when I only did so only twice. This is expensive.”

Chingoli is one of the primary schools which have high pupil population against few teachers. The head teacher explains that before the floods, they had seven streams and some classes were being conducted under the tree. He says the total population is now at 2 690.

“We have failed to create streams because the tents are few and so all Standard One pupils learn in one tent. That goes for the other classes as well. In Standard One, we have 528 pupils and it is hard to manage such a huge class,” laments Chiromo, adding that they tried to offer transfers to some pupils to go to nearby schools to control population, but many refused due to the long distance to those schools.

It is the same story in all the classes. The least number of pupils a class holds is 390 except for Standard Eight.

Chiromo reveals that this makes it hard for the teachers to give homework or class exercises to pupils.

The Education for All (EFA) goals recommend that each teacher should handle 40 students in a class. This means if the 2 690 pupils were to be put in classes with recommended number of pupils, the school would have required 67 teachers. But Chingoli has 42 teachers.

High teacher to pupil-ratio is a national problem and the Chingoli incident has a worse scenario. Educationist Dr Steve Sharra argues that the situation at Chingoli should be treated as temporary and should be replaced soonest “Anyone who has taught children knows how impossible it is to be an effective teacher with even 60 pupils in class.”

Also compromised at Chingoli is sanitation. After losing all the toilets and urinals, the school replaced them with ones constructed with black plastic papers. A number of female pupils described the facilities as unusable.

“They are transparent and one can see you from outside. I have never used them. When I see that I cannot hold myself, I just go home,” said a Standard Six girl.

One of the female teachers at the school revealed that most adult girls miss classes when they are in their menses because they have nowhere to hide to take care of themselves.

There was hope for some pupils to graduate from these tents to brick-made classrooms when the school received funds from Local Development Fund (LDF), but the block is still at foundation level. Chiromo says the school was given fresh land to construct school blocks and they are still waiting.

“No one should exaggerate our cries. Life is hard for us here and we are not enjoying the profession. We need the school blocks urgently. I am happy that Unicef has given us two more tents to help us create streams, but we want more of these as we wait for the permanent blocks. We lost stationery and we need replacement. As the school starts next week, we are not at peace because of these conditions,” he narrates.

Manfred Ndovi, spokesperson for Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (Moest) says government is aware of the situation, but the major setback is finances.

“Our challenge is finances. There is no money for the school in the 2015/2016 national budget and this is why after the incident, we engaged various organisations including the district commissioner’s office which has offered land for the new school. Unicef too came to our rescue by offering temporary classes made of tents. We are banking on LDF, but we are approaching donors to help us start the constructions because we cannot bank on the tents for a long time,” said Ndovi.