Malawi needs fairer, humane refugee policy

MICHAEL KAIYATSA

Human Rights Activist

In a few days, the government’s ultimatum for all refugees scattered across the country to return to Dzaleka Refugee Camp will expire.

Government claims that some 2 000 refugees, who are currently living and doing business among the communities outside the former prison, pose a danger to national security.

There is no sufficient evidence to back up that claim.

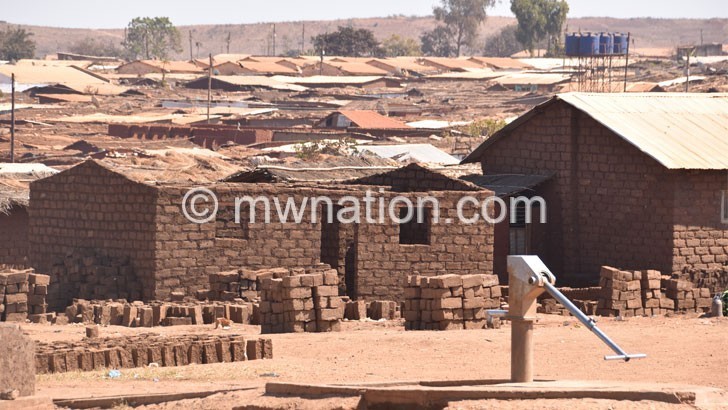

It is, however, a fact that the camp, as it stands now, is overcrowded.

A camp that was built to house 10 000 refugees is now holding over 48 000. The decision by the government could worsen the problem.

The decision to force all refugees to return to the camp could put a huge strain on the limited resources at the densely populated setting.

Currently, there is donor fatigue in supporting programmes for refugees in the camps. This is apparent with the constant reduction in food rations due to inadequate financial resources.

Since 2017, Dzaleka has been facing severe food shortages, which have seen monthly food rations given to refugees being reduced by half due to insufficient funding.

In addition, social services such as water, health and school spaces for children are not adequate.

Those who have visited the camp will agree that sanitation in the confined setting is appalling due to congestion.

Therefore, adding more refugees will make the situation even worse.

Besides, the country is going through the Covid-19 pandemic which has already claimed over 1 500 lives.

At a time like this, government should be decongesting places—not doing the opposite.

It is important to realise that refugees and asylum-seekers have rights which should be respected.

These rights include the right to life, the right to freedom of movement, the right to gainful employment and the right not to be forcibly returned to their countries.

These rights are affirmed, among other civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, for all persons, citizens and non-citizens alike, in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights as well as the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

Together, these instruments make up the International Bill of Human Rights.

Here in Malawi, these rights are, to a limited extent, affected by the nine reservations that the country entered to the 1951 United Nations Convention relating to the Status of Refugees.

The reservations were against rights such as the rights to naturalisation, health, education, freedom of movement and the right to engage in economic activity.

It is high time these reservations were reviewed because the conditions under which they were entered have changed significantly.

The reservations were entered at a time Malawi was hosting more than one million refugees, mostly from Mozambique. The situation is different now.

Malawi should publicly affirm its commitment to the letter and spirit of the 1951 Refugee Convention.

There are some international human rights organisations that are advocating for the abolition of the encampment policy as it has many negative implications on a human being. This position makes sense from a human rights perspective.

It is high time refugees were accorded a chance to settle anywhere they feel safe and engage in productive activities to realise their potential.

There is ample evidence to suggest that this policy of keeping people in camps indefinitely is doing more harm than good.

A refugee camp should be a temporary, not a long-term, solution.

Unfortunately, we have people in the camp who have been there for decades. They came as teenagers, but now they are grown-ups and yet doing nothing productive. They have wasted all their productive years in the camp.

Malawi needs a fairer, more humane refugee policy. Let those that can work or engage in business do so to support themselves, their families and Malawi’s ailing economy.

Some of these refugees are highly skilled. They include engineers, doctors, agriculturists and entrepreneurs in the camp. The country could benefit a lot from those skills.

Much as refugees came for safety, they need to lead an independent and productive life to meet basic necessities of life such as food, clothing and a decent living space.

They do not have to depend on the government to provide these things. It is too much for the taxpayer. n

The author is the executive director of the Centre for Human Rights and Rehabilitation (CHRR), which campaigns against the encampment of refugees in Malawi.