Mythical snake helps raise climate awareness

Sensitive campaigners are finding that belief in Napolo, a legendary multi-headed monster, is no barrier to environmental understanding and action, writes freelance journalist CHARLES PENSULO.

In March this year, Mary Phiri, 40, was at her home in Chilobwe, Blantyre City, when she heard a peculiar rumbling sound in the distance.

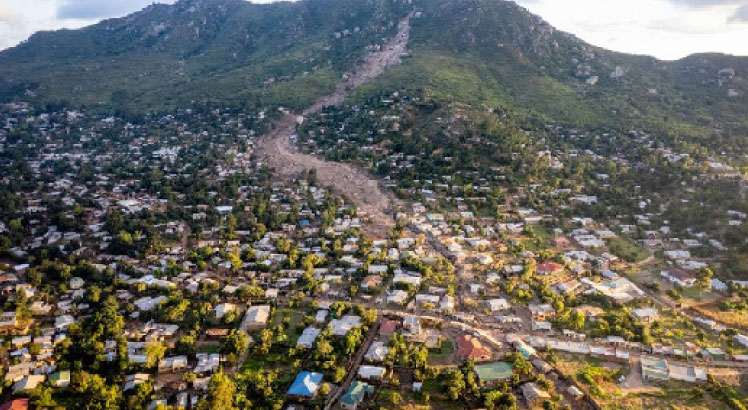

It got louder until an avalanche of mud and rocks hurtled down the nearby Soche Hill, sweeping away everything in its path.

The surrounding area was soon hit by flash floods that washed away homes, bridges and other infrastructure. A nationwide blackout followed as over 200 000 hectares of cropland were ruined.

For meteorologists, these impacts were not a surprise. Due to climate change, storm systems have become more intense and prolonged.

The longest-lasting cyclone affected millions of people across Madagascar and Mozambique, leaving thousands dead or missing, mostly in Malawi.

The world knew the tempest as Cyclone Freddy, another catastrophe in a series fuelled by the man-made climate crisis.

In the Southern Region, Phiri and others scrambled to make sense of the devastating events. However, to explain the inexplicable, they looked not to new science, but to an old myth: Napolo.

Legend has it that Napolo is a giant multi-headed snake that lives in a deep sacred pool under the mountains. When it emerges from its hiding place, devastating floods and landslides ensue amid cries and drumming echoes across the region.

“This was not a natural occurrence,” Phiri told African Arguments while standing on remains of her two-bedroom home. “Nobody can dispute that it was Napolo.”

The story of Napolo can be traced back to a flash flood in 1946. Ever since, several disasters have been blamed on the migratory snake.

In many communities, deeply embedded traditional beliefs have remained strong amid growing awareness of climate change and manmade environmental crisis.

“The scientific explanation of flash floods is enlightening and intellectually liberating, but, in terms of charisma, it cannot beat the image of a fiery and smoky serpent roaring down the mountain slopes to the accompaniment of the loudest drums, flutes, and whistles,” says writer-turned-politician Ken Lipenga, who now spends his retirement hiking mountains.

For some, the predominance of traditional beliefs might be a barrier to sensitising people about climate change and the growing risks from natural hazards. However, several Malawian artists and environmentalists have used the well-known myth of Napolo to spread important messages.

Sosten Chiotha, the regional director of the Leadership for Environment and Development in Southern and Eastern Africa, has been engaging with local perspectives on climate change since 2008.

He says that certain traditional beliefs are directly harmful, citing the example of elderly women being blamed for causing dry spells.

“If the explanations are detrimental, we should dismiss them,” he says. “We need to completely dispel the ones that are harmful with alternative scientific explanations.”

However, his work has also found that some familiar legends help campaigners widen understanding and ensure their messages resonate with existing beliefs and practices in communities.

“The legend of Napolo is harmless since you can tell the people how they can prepare for it by planting trees and staying away from risk areas,” says Chiotha.

Some Malawian artists have been doing just this to share messages about climate change in ways that work with—rather than against—traditional ways of relating to nature.

Elias Gaveta of Conservation Arts Malawi, for instance, runs a folklore project with local chiefs to educate younger generations. The elders share knowledge about the past and how things have changed from their traditional viewpoints, which Gaveta and his colleagues then complement with scientific explanations.

“What we’re doing is just adding in science and climate change messages,” he says. “Cyclones are natural and Napolo was a cyclone. The only difference now is that the impact and frequency of those cyclones has been enhanced with human activities and that we do not have adequate green infrastructure to protect our home and farms.”

By engaging with communities in this way, Gaveta has also learned more about local legends in ways that have helped him shape messages about the environment and sustainable practices.

“There is an interesting side to Napolo,” he says. “Some people told us the snake would come out when it’s angry or provoked, so we advise them not to cut down trees or encroach the mountains to avoid angering those spirits.”

Rapper Evans Muzik, born Evans Chimwala 30 years ago, takes a similar approach using music. His recent song Napolo narrates the story of a victim of Cyclone Freddy. The song consoles more than 2.2 million people affected by cyclone.

The musician says the legend can help—not hinder—spread understanding of climate change and man-made environmental damage.

“In fact, it may have long been the underlying message of the myth,” he suggests. “My take is that our ancestors understood that Napolo occurred whenever people had wronged nature, including cutting down trees. We should believe the legend.”