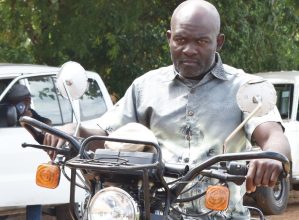

Phiri: The beggar who mirrors society’s poverty, indifference

There is no way that odd-looking John Phiri could be allowed to enter a United Nations (UN) session assessing how countries have competed, in recent years, to score highly on the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).

Even if Phiri could be the epitome of patriotism by hoisting a brand-new Malawi flag, reflecting a feeble right of entry into the glittering and air-conditioned UN chamber in New York City, United States of America, he would surely be barred.

A former robust young man, Phiri has been reduced to a street beggar.

He crawls on all fours. His clothes are filthy and, it appears, he has little motivation to bath or clean himself up.

It is as if society condemned him to death decades ago. He has known a life of rejection and dejection that would shock anyone who would care to look at him closely and hear his heart-rending story.

Last week, The Nation engaged with a surprised Phiri, who said it was the first time anyone cared to hear his story.

“I feel that society hardly cares what I am going through. As a matter of fact, most people brand me a mad man, for whom they have neither time nor feelings,” he laments.

Phiri mirrors the society’s poverty and indifference. He represents the country’s pathetically poor and helpless people who would trigger an embarrassing loss of points for the besuited and jet-lagged Malawi representatives at the UN.

Says Phiri: “I always cry that God gives me two things that matter most in my life: healing and capital for any business. These can free me from the abject poverty I am in.”

Aged at least 65, the man suffers from what appears to be a virtual paralysis of both his legs. From his waist, downward, his body had been bloated, like that of a malnourished child, for some time.

Explains Phiri: “For many months, I felt total numbness in these legs and feet. But now I feel much better, as I feel sensations.”

His feet are in an odd-looking torn pair of shoes stuffed with dirty cloths and cotton buds strapped together by strings. He says he puts together the odds and ends on his feet as a cushion to his sore feet.

“If only I could walk again, or—at least—if the great pain I feel could go away, I would be a relieved man,” says Phiri, who wobbles painstakingly when he tries to walk.

On a daily basis, he slowly crawls from his sleeping ‘den,’ all the way to his strategic begging points in Lilongwe. He is often with a dirty bag full of his prized food and clothes. He thrusts the bag ahead as he crawls to his begging posts.

Phiri’s prime begging post—along Mzimba Street, where he also cooks his meals— is only about a kilometre away from where he sleeps. He covers the distance in about an hour’s time.

When he feels a burst of energy, and he wants to try his luck on the busy Kenyatta Drive—some three kilometres away— he spends just over twice that time in his chequered movement.

Phiri sleeps rough-shod, on an open ground near Chisomo Private School, just across the Lilongwe River Bridge, after passing Kamuzu Central Hospital (KCH) on the way to Mchesi Township.

All things being equal, Phiri could have found his healing from any of two sources close to him.

From a medical sense, the nearby referral KCH could have long assisted him. And from a spiritual aspect, the many anointed men and women of God doing healing miracles in the half-dozen churches in the area could have seen his spot of bother and could have sorted him out several times over.

But even if he is an obvious case of suffering and pain, as he crawls around their very vicinity, both sources have conspicuously ‘ignored’ him.

“Some hospital workers have branded me a mad man who should not even bother to seek medical attention… This is why I have no proper diagnosis for this disease and this is also why I am not taking any drugs right now,” the man laments.

Phiri—who comes from Madzuwa Village, near Nkhoma, in Traditional Authority (T/A) Mazengera in Lilongwe District—partly believes he was bewitched by some of his relatives.

“Some of my enemies put juju, including a maggot and a weevil, into my food when I was a strong middle-aged young man fending for myself by doing grass-fencing and latrine-digging and construction jobs for clients in Lilongwe,” he recalls.

He says he later opened bowels and developed persistent stomach pain, with the subsequent bloating and paralysis of his feet.

“Certain people, including some medical workers, say I have HIV and they have recommended that I should eat and drink hot food and liquids, so that some of the viruses should die. I try to live up to that instruction on a daily basis, whenever I have food to eat,” he explains.

He says on most days, he is lucky to be given a total of K500.

“I usually receive only K200 and, from this amount, I go to Mchesi Township Market, to buy some flour and my standard relish, utaka. That affords me the day’s meal,” he informs, grimacing.

But Phiri, who has a Catholic Church background, says he is grateful to God for moving the hearts of several people who have contributed substantially to his survival.

He adds, with a glint in his eyes: “There have been days when a few individuals have given me K5 000 (US$11) or K2 000 (US$4) at a go. When this happens, it affords me the rare chance of budgeting for my food for several days. But such big help happens very rarely.”

After being bundled out of his last ‘comfortable’ shelter, at a coffin workshop some three months ago, Phiri has resorted to sleeping at an open-air site near the lower Lilongwe Bridge.

But what about the biting cold weather, punctuated by the persistent Chiperoni winter rain showers?

“When no one truly cares about me, do I have a choice but to sleep rough? I have experienced these harsh weather conditions for more than 20 years now. My fear is not the coldness nor the wetness I experience … My bigger fear is where else I will lodge if the police chase me from what seems my last post,” he stated, hinting that there is a limit to the shocks his advanced age can take.

Throughout the interview, Phiri proved that he was a man with a sound mind.

When briefed about Phiri’s case, Principal Secretary of the Ministry of Gender, Children, Social Welfare and Disability, Mary Shawa, was cautious and said she would like to have the full facts of the matter first.

“We will send our social workers to the site, so that we get to the bottom of the matter,” she said on Tuesday.

But she expressed disappointment that the ministry has exposed several supposed destitute people who feign, or exaggerate, a disability to win pity and assistance from members of the public.

Centre for Human Rights and Rehabilitation (CHRR) executive director Timothy Mtambo seemed stunned that, in this day and age, such poverty and indifference could be allowed to thrive.

“This story tells volumes on how the society has ignored its human obligation of caring for one another. It is clear, from his (Phiri’s) testimony, that he has not enjoyed his right to health,” he noted.

The human rights activist said although the Ministry of Gender, Children, Social Welfare and Disability has done some commendable work lately, it needs to step up the efforts to improve the welfare of the destitute people, partly by being proactive and inclusive in seeking solutions.

In her remarks, Malawi Health Equity Network (Mhen) executive director Martha Kwataine expressed shock and sadness that society can condemn fellow human beings to such destitution.

“We have all failed, as a nation, to take care of the destitute.

“Even if this man were mad, the government has a mental hospital in Zomba, where he could have been taken to for proper diagnosis and treatment of the other illnesses. Even mad people have the right to health and the right to life and the state is obliged to providing health-care to its citizens, commensurate with their needs.”