Quota system: Good policy gone bad?

Last week, we showed how the equitable access to public universities (also known as quota system) disadvantages students who learn in poor schools over those who learn in better schools. This week, EPHRAIM NYONDO continues the debate by examining inequalities in the access to public secondary schools in Malawi and how quota system is failing to address such inherent inequalities.

The equitable access to public universities, popularly known as quota system, was re-introduced in 2009 by late president Bingu wa Mutharika’s regime.

What was fundamental in the discourse, like the case was when the system was first introduced in 1989, was that public universities are a national cake that needs to be shared equally.

However, it was felt that some regions and districts in the country were enjoying a bigger share of the cake by sending more students to public universities than others.

In other words, the merit system favoured some regions and districts; in the process, fuelling inequalities between regions and districts in the access to public universities in Malawi.

So, to solve such an inequality of access, government, through the re-introduced quota system, reserves 10 places for each district and the remaining spaces get shared according to population size of the districts.

However, some education experts argue that what the regional and district imbalance that the current quota system seeks to address is not so much an issue.

They advance that the biggest problem in the access to public universities is not the inequality between districts and regions, but that most of the students who make it to public universities are those who come from best schools mostly in urban areas. Those that go to poor schools barely make it to college because they do not have much opportunity.

To get to the core of this, one needs to understand the nature of public secondary schools in the country.

Public secondary schools in Malawi are in two major categories: conventional secondary schools (CSSs) and community day secondary schools (CDSSs).

CSSs are national secondary schools which take students from all over the country and district secondary schools that are just for learners in that district.

CDSSs, on the other hand, cater for children living around the school within a 10km radius.

Another definitive difference between these two public secondary schools lies in geography.

According to a 2000 report by Malawi Institute of Management (MIM), the majority of CDSSs are in rural areas.

The implication of this finding, it can be argued, is that these schools mostly cater for the rural population where the majority of the poor live.

Dr Samson MacJessie-Mbewe, once an education lecturer at Chancellor College but now director of Higher Education in the Ministry of Education and Technology, and Dr Foster Kholowa, senior lecturer of education at Chancellor College, in their study report titled The Malawi Education System and Reproduction of Social Inequalities: Implications for Education for Sustainable Development—use the Central East Education Division (CEED) as a microcosm to examine the implications of inequality regarding access to quality education between rural and urban students.

In their study, MacJessie-Mbewe and Kholowa found that CEED has 122 public secondary schools in rural areas, of which 101 are CDSSs, representing 83 percent of the public secondary schools in that division.

According to the CDSS policy, these schools are all day secondary schools and all their pupils “will be drawn from primary schools within the local catchment area of the CDSS [and] this catchment area will not exceed 10 kilometres.”

The implication of this policy, when applied to the division studied, means that CDSSs, which mostly offer substandard education, are the preserve of rural-based children.

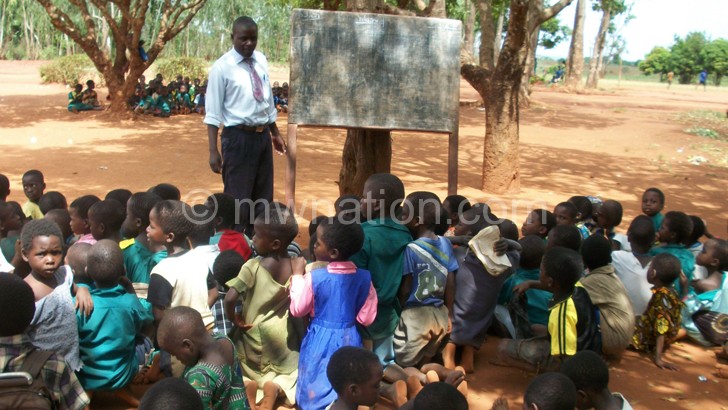

CDSSs are notorious for lacking teaching and learning materials, having unqualified teachers and poor infrastructure compared to CSSs.

MacJessie-Mbewe and Kholowa argue that their finding is sufficient to conclude that if the majority of the CDSSs are in rural areas and students who go there are taken from the surrounding primary schools, it follows that the majority of the children who go to CDSSs are from rural areas and from poor families.

In contrast, most CSSs are either in urban areas or townships—where most of the middle to upper class citizens live with their children.

The authors contend that even though theoretically some CSSs were supposed to draw children from both rural and urban primary schools, most of the children who attend them come from very good primary schools with adequate and well-trained teachers who are mostly located in the urban or township areas.

According to 2007 government records, qualified teacher-pupil ratio in primary schools in the 2007 academic year was 1:95 in rural primary schools against 1:49 in urban primary schools.

This, add MacJessie-Mbewe and Kholowa, means that urban primary schools have more qualified teachers than rural primary schools and chances of urban primary schools sending children to CSSs are higher than rural primary schools.

“This is so because with more well-qualified teachers, urban schools provide higher quality education to their pupils than rural schools whose teachers are less qualified.

“This follows the selection procedure to secondary school as done by the Ministry of Education. Since the education system in Malawi is so competitive, only those who get very high grades in Primary School Leaving Certificate Examinations [PSLCE] are selected to conventional secondary schools while those whose performance is lower are selected to CDSSs,” they write.

The teacher-pupil ratio in CDSSs is also worse than in CSSs.

Official statistics show that student enrolment increased from 67 percent in 2005 to 70 percent in 2007 in CDSS compared to CSS, where it fell from 33 percent in 2005 to 30 percent in 2007.

Even on the availability of qualified teachers, CSSs rank higher than CDSS.

A 2002 Ministry of Education baseline study for the secondary education project found that among the secondary schools surveyed, only 10 percent of the teachers in CSSs were not qualified against 77 percent of teachers in CDSS who were unqualified.

The story is not different when it comes to teaching and learning materials. As observed by MacJessie-Mbewe and Kholowa, most CDSSs do not have science laboratories and as such, science subjects are not adequately taught in these schools.

Absence of electricity in rural areas is also a setback for a rural learner.

With less than seven percent of about 17 million people in the country having access to electricity, especially in urban areas, most CDSSs, which are in rural areas, have no electricity.

This, arguably, makes it difficult to teach some subjects that require electricity, especially science subjects that demand conducting experiments.

These contrasting instances have had drastic effects on the overall performance of students in CDSSs.

For example, in 2000, only 14 percent of students in CDSSs passed MSCE compared to 33 percent in CSSs.

The greatest challenge, as noted by MacJessie-Mbewe and Kholowa, is that education in Malawi is competitive and national examinations determine who should move from one level to the next.

“However, the mobility from one level to another does not depend on passing the national examinations only, but also selection. For example, not all students who pass MSCE go to university, but only those who pass very highly.

“The selection, unfortunately, is based on merit and not on what type of secondary school one attended. Consequently, because of the many problems that CDSSs face, very few students are able to pass the final national examinations as compared to students in CSSs, and furthermore, a negligible number of students in CDSSs manage to make it to university,” they write.

Given the urban-rural education inequalities outlined, is the quota system—guised as equitable selection into public university— tackling the most fundamental inequality being the rich and the poor problem of our time?

Limbani Nsapato, acting regional coordinator and policy & advocacy manager for Africa Network Campaign on Education for All (ANCEFA) says the quota system has offered solutions in some countries and is good idea in the short term, but the way it has been implemented in the country has had shortfalls in terms of planning and targeting.

“Broad-based consultations have not been held to ensure public ownership, and targeting has just looked at district level without other factors such as disability and rural-versus-urban factors. There has also been lack of transparency in the way the system is being managed. As such, while it can be argued that it has provided opportunities to some marginalised populations, it may not be fully responding to the problem at hand,” he said.

On his part, Benedicto Kondowe, the executive director of Civil Society Education Coalition (CSEC), says the quota system does not respond to deep-seated inequalities in the education system as it is more addressing symptoms.

Quota system does not address intra-district inequalities rather than regional as such it is technically accepting intra-district inequalities, he adds.

“The point being made here is that there are disparities within a given district, for example, between conventional and CDSS that any meaningful policy should aim at bridging. Unfortunately, quota system does not look at such disparities in terms of how differently schools are resourced within the district in terms of staffing, libraries and laboratories etc.

“What we needed to do was to carefully assess why certain districts are performing better than others despite being more resourced so that we deal with root causes of such disparities.

“My view has been to look at long term incentives to trigger better results than the way the quota system is being implemented which in my view is too discriminatory. The policy also runs contrary to democratic principles of fairness. The UDHR classifies tertiary education as competitive, implying that access to it has to be based on equal grounds of performance,” he said.

MacJessie-Mbewe also shared his views.

The quota system is good affirmative action but the problem was that it was mis-targeted, he said.

“Since the major emphasis was on region, it became politicised and tribalistic. The quota system should look at the rural-urban inequalities in all districts. Each district has the rural disadvantaged and the urban advantaged, but also there are some districts which are mostly rural and the children’s performance in these is not good,” he explained.

So the quota system as of now, he emphasises, does not fully respond to the problem at hand.

“It needs to be reformed and also should be participatory in the reforming so that people should understand why the quota system is in place. You will observe that most of the people who argue for and against quota system do not have a theoretical background about it and then their arguments are just emotionally charged,” he said.

Dr Steve Sharra, blogger and lecturer in education at Catholic University of Malawi (Cunima), noted that the quota system was established with the aim of addressing regional inequalities in access to higher education, but it is not administered in a way that achieves its goal.

“Going by the figure that less than one percent of poor Malawians find their way to a university education, the quota system is failing the majority of poor Malawians and serving wealthy Malawians.

“As Limbani Nsapato has argued repeatedly, a win-win quota system would give more weight to economic class, gender, and disability so as to enable more Malawians from poor and disadvantaged backgrounds access university education. The current setup does not consider those aspects,” he said.

Unarguably, there is something fundamentally wrong with the current quota system. It needs to be reviewed.