Smallholder farmers’ survival in times of floods

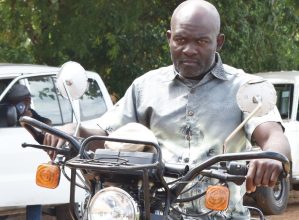

While some flood victims queue to receive relief items at Bangula Primary School Camp in Nsanje, Geoffrey Mbenje (70) of Kampira Village, Traditional Authority (T/A) Mbenje relaxes under a tree. He is planning to go back home to replant his field.

“My child is on the queue to receive our portion,” Mbenje begins to justify his point; “I am happy that we are getting something to support our lives, but this is temporary. I am more concerned about how my family will survive after we leave this place. Relief items are temporary and have never been sufficient.”

alnHe says his maize field sits on slightly higher land and he is confident that the waters have receded and he can now work on it to replace the lost seedlings.

alnHe says his maize field sits on slightly higher land and he is confident that the waters have receded and he can now work on it to replace the lost seedlings.

“The challenge is that if I delay working on it, then I will not realise better harvests because the growing season expires in April. If I am to get better yields, I have to replant before mid-February because that is when the rains begin to cease,” he says, while lamenting that every year his field is affected by floods and replanting does not give him enough yields.

In Malawi, the start of the growing season has been unpredictable due to changes in rainfall patterns influenced by climate change. A Unicef report titled ‘Climate change and smallholder farmers in Malawi: Understanding poor people’s experiences in climate change adaptation’ reveals that rains now start three months later than they did 10 years ago. It says rains used to come in October not December as it is now.

“Changes in rainfall have affected the growing season. For example, maize used to be planted in October, but it has now shifted to December,” reads the report in part.

Unfortunately, those who lose their crops to floods do not reap good yields when they replant. Mbenje knows this. His crops have been swept away by floods several times before. He says efforts to replant have not yielded much because the planting is done late when the rains are receding and soil temperature, another important component for seed germination and plant growth, is too low.

The farmer says for the past seven years, yield at his farm has been declining.

“I used to harvest 22 bags of maize from my garden, but now, I only get less than 15,” says Mbenje, who attributes this to climate change.

Mbenje is one of thousands of farmers who are struggling to cope with climate change and its impacts.

The recent floods that have displaced over 174 000 people in 15 districts of the country are said to be due to climate change. They have washed away seedlings on 135 hectares and fears of food shortages this year are already gripping.

Malawi largely depends on agriculture. Farming contributes 30 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). It also brings about 80 percent of the country’s foreign earnings. This makes it a must for Malawi to find ways to help farmers adapt to climate change and survive.

However, as lamented by Mbenje and some farmers in Muloza Mulanje, adapting to climate change has never been easy.

Bigborn Ernesto, chairperson of Mujiwa Village Development Community (VDC), which manages farmers’ clubs in T/A Ndala’s area, explains that climate change has brought a short growing season characterised by heavy or little rains, long dry spells and soil infertility as a consequence of soil erosion.

“These are tough times for a smallholder farmer,” says Ernesto, adding; “We are advised to grow early-maturing seeds, but they are expensive.”

Across Malawi, farmers are being encouraged to plant hybrid and early-maturing crop varieties. However, this is not enough. The soils have been overused and need frequent fertiliser application.

“Government introduced the Farm Input Subsidy Programme (Fisp), but how many have access to the inputs? The rest of us have to buy and where do we get the money?” wonders Ernesto.

So how are smallholder farmers surviving?

Most farmers admit that their yield has been dwindling over the years.

Christina M’bwerera, a farmer in Thyolo, says she cannot remember when she last harvested enough maize to feed her family the whole year.

“What I produce these recent years is consumed within just five months. This means we have to find money to buy food for the rest of the year. It is not easy,” says the mother of three.

M’bwerera says her family survives because sthey eat nsima once a day. They only take it for supper. In the morning, they have porridge while they have pumpkins, pigeon peas or cassava for lunch.

The widow reveals that most farmers know that the way to go is practising modern agriculture, but it is expensive. She says they cannot afford buying hybrid maize, hence they rely on local maize.

Noting that the world cannot do without food, agriculture was made one of the priority areas in the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which expire this year. As the first MDG, nations agreed to invest in agriculture and reduce by half the proportion of hungry people. Malawi, through Fisp, has been named among countries likely to achieve the goal. Nonetheless, experts predict increased hunger this year following the recent devastating floods.

Khadija Bakili, agriculture extension development officer (Aedo) for Ngala section under Nkwinda Extension Planning Area (EPA) in Lilongwe, says most farmers are struggling to survive because of poor civic education on climate change and adaptation.

Bakili says Aedos are trying to bridge the gap by encouraging farmers to practice conservation agriculture, apply manure and practice irrigation farming, but a lot needs to be done. She, however, says farmers’ negligence and resistance to change are some of the setbacks affecting the climate change adaptation efforts.

“We need to promote maximum land utilisation and influence smallholder farmers to be flexible to adapt to sudden weather changes. In times of climate change, every farmer should be influenced to adopt modern agriculture to achieve high yields because research shows that yields continue to dwindle at farm level,” says Bakili.

However, the Unicef report indicates that existing local government capacity cannot support the challenges smallholder farmers face in adapting to climate change as there is lack of knowledge of disaster and environmental management techniques among farmers. The report also notes that development factors exacerbate climate change impacts and inappropriate government policies are undermining attempts by farmers to diversify their crops…

In the second part of the series, we look at how smallholder farmers could best survive in these times of climate change in relation to the post MDGs goals.