Social cash transfer: A case for Malawi

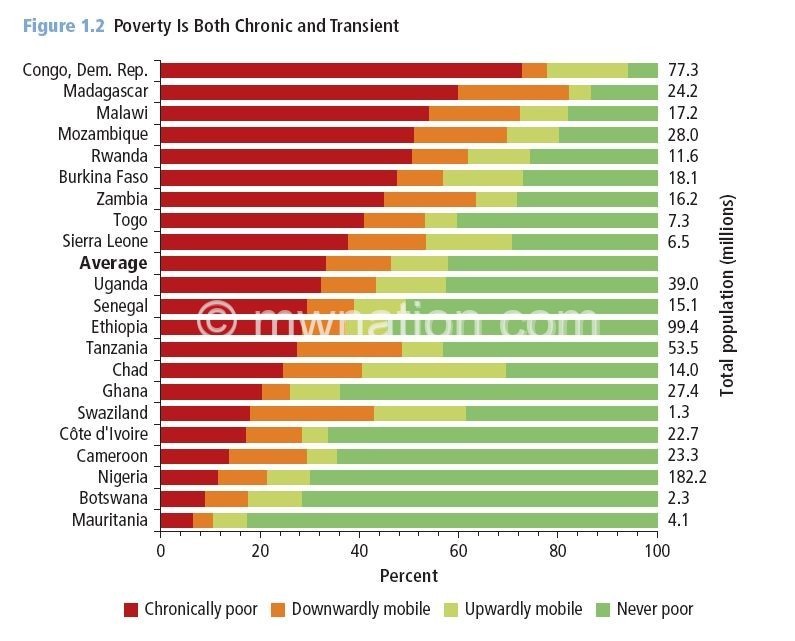

Despite economic growth and improvements in many dimensions of welfare, the World Bank reports that poverty remains a pervasive and complex phenomenon in sub-Saharan Africa, including Malawi.

According to the Bretton Woods institution, approximately two people in five live in poverty, and, because of shocks, many others are likely to fall into the poverty trap. Part of the agenda to tackle poverty in Africa in recent years has been the launch of social safety nets programmes.

Largely absent from the continent until the early 2000s, social safety nets are now included in development strategies in most African countries. The number of social safety nets programmes has expanded greatly.

In several countries, the expansion has arisen concomitantly with significant investment in core instruments of national social safety net systems—such as targeting systems, social registries, and payment mechanisms—that have progressively strengthened the systems and raised their efficiency. Malawi was not spared.

The Malawi Social Cash Transfer (SCTP) also known as Mtukula Pakhomo is an unconditional transfer targeted to ultra-poor, labour-constrained households. The main objectives of the SCTP are to reduce poverty and hunger, and to increase school enrolment.

The programme began as a pilot in 2006 in Mchinji and was subsequently expanded to an additional six districts in 2007, and by September 2017, the programme was reaching over 777 000 beneficiaries in more than 174 500 households across 18 districts of the country, including approximately 430 000 child members.

Transfer amounts for the SCTP vary by household size and by number of school-age children present in the household.

It is estimated that approximately over 500 000 households in Malawi are ultra-poor. Of that group, about 300 000 are ultra-poor due to the structure of the household with few or no able-bodied adult household members. These households have either no household member who is fit for productive work or have a high dependency ratio—they are labour constrained.

The shift in social policy towards social safety nets reflects a progressive evolution in understanding the role that social safety nets can play in the fight against poverty and vulnerability. Evidence shows that these programmes can contribute significantly and efficiently to reducing poverty, building resilience, and boosting opportunities among the poorest.

In its recently publication titled Realising the Full Potential of Social Safety Nets in Africa, the World Bank puts Malawi among five programmes with significant impacts in the region.

According to the bank, the impacts on consumption increased by $1.79 (about K1 300) per $1 (about K740) transferred through the programme in Malawi.

Assuming that rotation would allow the same beneficiary to work 24 days, the bank observes that monthly amounts would be equivalent to $73 (about K54 000) in the Malawi Social Action Fund (Masaf), way above the minimum wage at K25 000 per month.

Overall, African countries spend an average of around 1.2 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) on social safety nets, compared with a global average of 1.6 percent in the developing world, according to the bank. This represents about 4.6 percent of total government spending.

The bank urges that for the full potential of social safety nets to be realised in addressing equity, resilience, and the opportunities available to poor and vulnerable populations in Africa, programmes need to be brought to scale and sustained by among others solving a series of technical issues to identify the parameters, tools, and processes that can deliver maximum benefit to the poor and the vulnerable.

“Increases in agricultural harvest yields and the value of sales were found in the Ethiopia Social Cash Transfer Pilot Programme, the Malawi SCTP, and the Zambia Child Grant Programme over 60 percent of beneficiaries of the Malawi Masaf Public Works Programme (PWP) among the poor. However, a certain share of resources goes to richer households.

“Some limitations in targeting are technical because it is hard and costly to assess the welfare status of households effectively and dynamically. However, the decision to target particular groups is also a political one.

“Indeed, selecting eligible groups is sometimes driven by the need to generate support among the population and decision makers for social safety net programmes,” reads the report in part.

In a paper titled Are Social Safety Nets and Input Subsidies Reaching the Poor in Malawi?, the International Food Policy Research Institute (Ifpri) has said many households who receive the benefits of social safety nets (SSNs) programmes do not satisfy the targeting criteria, while many who satisfy them do not benefit.

Ifpri, however, observed that considering that in the case of Farm Input Subsidy Programme (Fisp), random assignment did not benefit the poor any less than deliberate targeting, it is unlikely that a simplification of targeting criteria would further impair the effectiveness of targeting compared to its current state.

According to the paper, data related to the Food Insecurity Response Plan and SCTP suggests that this was at least partly due to poor adherence to targeting guidelines while data related to Fisp suggests that elites are less likely to capture the programmes when beneficiaries are selected at random rather than through community-based approaches.

“Transfer programmes targeted the poor more heavily than the rich, but still failed to exclusively target only the poorest segments of the population. In fact, the benefits of SSNs reach non-poor households as often as they reach poor and ultra-poor households combined.

“Input and employment subsidies, delivered primarily through Fisp and the Malawi Social Action Fund, reached mainly the middle segments of the population in terms of wealth. It is likely that ultra-poor households were less likely to be reached by these programmes due to their labour constraints, while the non-poor were less likely to benefit because of lesser need. This seems to be the case regardless of the targeting approach,” reads the paper in part.

Earlier, agricultural expert Tamani Nkhono-Mvula urged farmers to desist from relying heavily on rain-fed agriculture and invest in climate smart agriculture to scale-up productivity and overcome climate change effects.

According to the Integrated Household Survey (IHS2) of 2005 45 percent of households in Malawi live below the poverty line, 17 percent live below the ultra-poverty line. People living below the ultra-poverty line tend to suffer from chronic hunger during most of the year. As a result they tend to be physically weak, they also have sold or consumed their productive assets, given up investing in the future and often die of preventable illness.