Whither integrity testing?

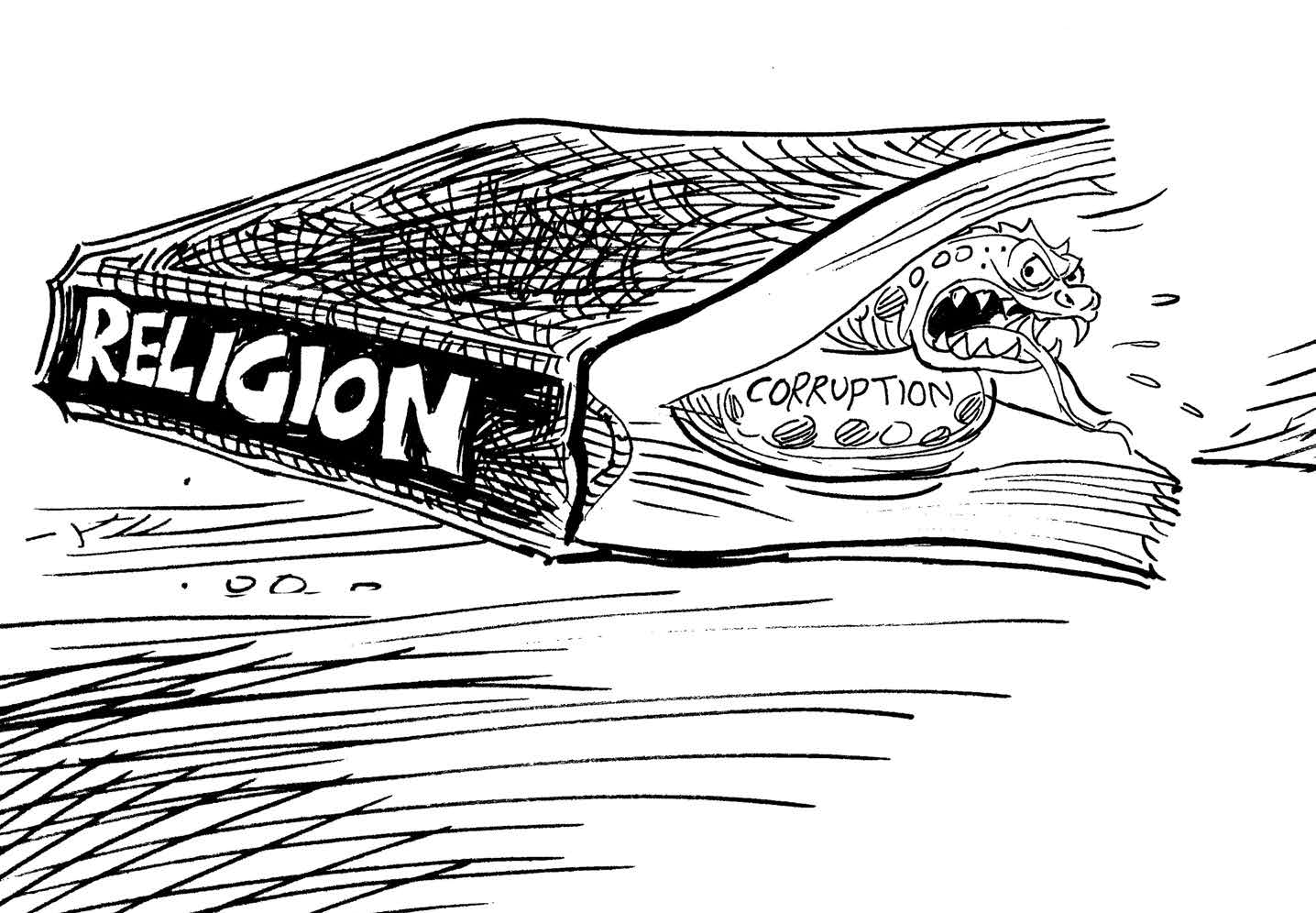

Promoting a culture of integrity where corruption is widely repudiated and denounced in the interest of the common good is one of the three prioritised concrete goals of the National Anti- Corruption Strategy I I (NACS II). The other two are to improve qual i ty and accessibility of public services for the benefit of all Malawians and to strengthen the rule of law to ensure that crimes of corruption are effectively detected, investigated and ultimately punished. These two goals are not for today. Today’s entry focusses on integrity and asks whether there is a place for integrity testing in both the public and private sectors and whether there is value in administering integrity or honesty tests to employees.

Employee integrity tests are a type of personality test that assesses job applicants’ tendency to be honest, trustworthy and dependable . By mapping candid a te s ’ p references towa rd s certain behaviours that are linked to integrity issues, integrity tests attempt to predict the potential of coun ter p roduct i ve workplace behav iours a m o n g e m p l o y e e s . Historically, integrity tests became popular after the fall from grace of lie detectors or polygraphs. Integrity tests come in two forms: overt integrity tests and covert integrity tests. Overt integrity tests are clear-purpose tests that directly measure attitudes that relate to dishonest and counterproductive behaviours while cover t tests are personal i ty – based tests that assess integrity by proxy – such as conscie n t iousness and aspects of emotional stability.

By attempting to promote a culture of integrity, NACS II recognises that a lack of integrity is associated with counterproductive b e h av i o u r s s u c h a s disciplinary problems, theft, absenteeism, cyberloafing, sabotage and violence. Cor ruption, given how devastating it has been, needs to be seen as the ultimate counterproductive behaviour. Clearly, a lack of integrity will certainly have stakes in the other two goals of NACS II. In view of the link between integrity or lack thereof and counterproductive behaviours there is utility for integrity tests.

There is evidence of integrity tests’ high returns on investment in settings where counterproductive behaviours are highly disruptive to organizational functioning. For instance, theft of valuable property or sensitive information can bring organizations down to their knees. As a country, we have already witnessed the damaging effects of corruption on some of our national assets, including the environment. In as far as integrity testing addresses the challenge of counte r p ro d u c t i ve behaviours in organizations, t h e n o bv i o u s l y i t i s something that should be considered as part of the arsenal used in personnel selection – and therein lies some challenges.

Of late I have come across industry players who have taken steps to include integrity tests, and it appears others have already taken integrity tests on board. Despite the utility of integrity tests, there are inherent challenges assoc i a ted with thei r use. Faking, especially with regards to over t integrity tests, has been observed. Just like the use polygraphs in yesteryears, integri ty tests have a fare deal of legal, ethical and validity challenges to contend with. This notwithstanding, integrity tests used alongside other assessments and during later stages of recruitment when the candidates’ pool has been narrowed down have been effective. Given what we have seen so far and industry’s willingness to decisively deal with counterproductive behaviours in their ranks and file, there is room for the ut i l i sat i on of integrity tests. Af terall, as a people, we aspire a culture of integrity and we all need to act in ways that communicate such intent at both personal and organisational levels.