Beware of social norms, pluralistic ignorance

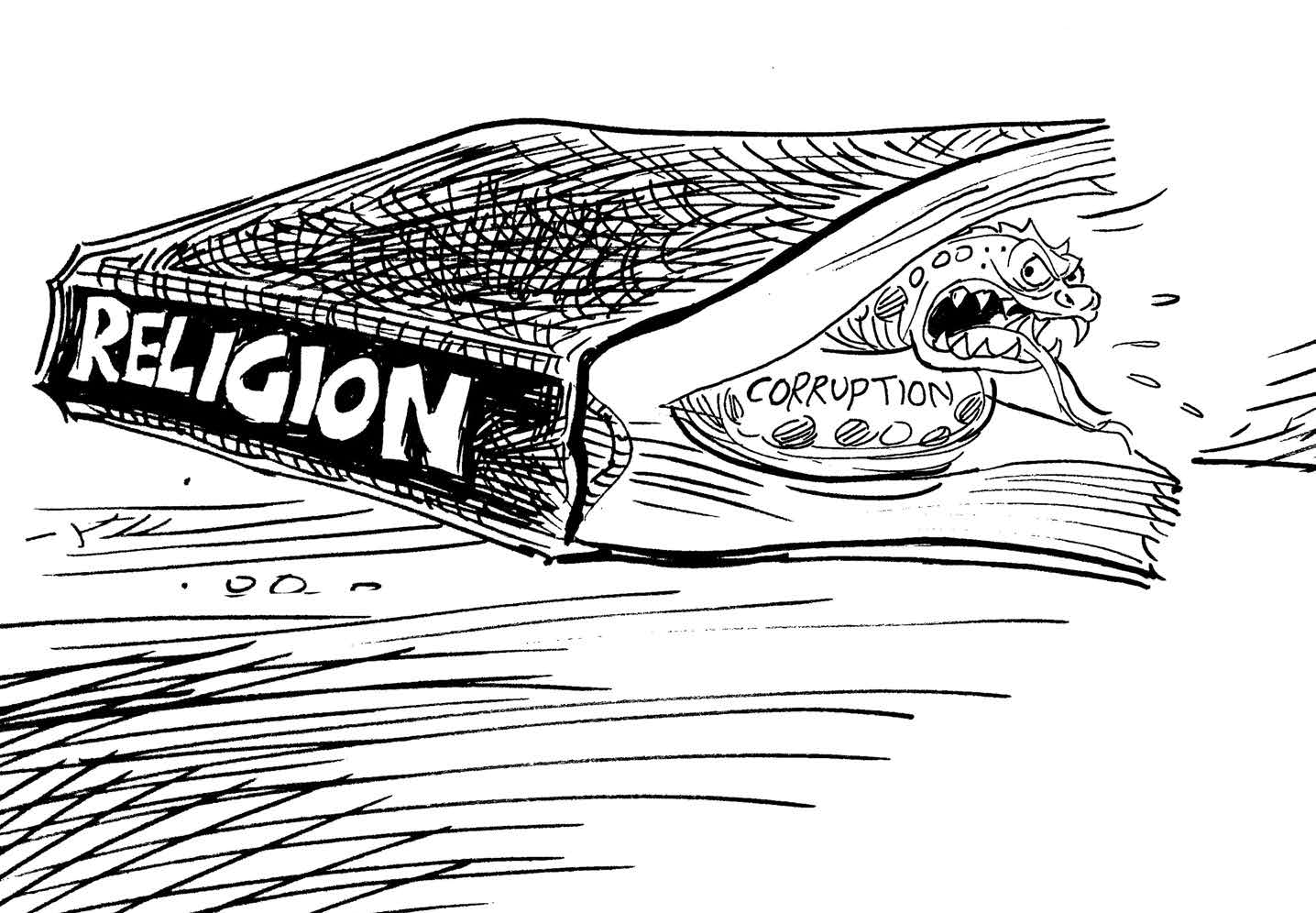

Given the negative e f f e c t s t h a t corruption has on our society, and the existence of laws, conventions and messages against corrupt behaviour, it is quite understandable that many people find corruption generally inacceptable.

However, this has done little to prevent corrupt behaviour from occurring. In attempts to understand the complex issue of corruption, some scholars or campaigners on the matter have turned to social norms for insight and for effective interventions.

Defined as shared understandings that govern behaviour of members of a society, or unwritten rules about the right way to behave within a group, social psychologists distinguish between descriptive norms a n d i n j u n c t i ve n o r m s .

Descriptive norms convey information about how most people behave in a given situation while injunctive norms provide information on whether a specific behaviour is appropriate or ethical. These norms matter because they can structure behaviour and attitudes, including those related to corruption. This entry therefore looks at the dangers that social norms pose through the ways in which they sustain corrupt practices.

Social norms matter. As informal rules, they provide motivation to engage in behaviour. They do so by shaping mutual expectations about what is appropriate and typical behaviour in a particular social context. In other words, what we believe others do or what we think others expect us to do is a product of social norms. Social norms matter because they help us fit in, they strengthen our sense of identity and they offer predictability of behaviour. As a result, and because of potential sanctions for social norms’ violations, we sometimes find ourselves acting contrary to our own attitudes.

It is not surprising when some people are caught up in corruption traps, sustaining corrupt practices, because of the social pressures created by the threat of social sanctions for norm violations. For instance, failure to report corrupt activities, which in turn sustains those activities, could be a result of a social norm that reinforces the belief that reporting observed corrupt activities would not change anything. This is despite the individual knowing that both the activity in question and failure to report are both inappropriate.

Using social norms as lenses for viewing corruption holds that corruption can only survive if social norms accept it. For example, stories are told of drivers who bribe traffic police officers for traffic rules violations or buy their way for ease of passage because, as per descriptive norms, they believe that these kinds of corrupt activities are widespread and there is a high likelihood of the corrupt activity succeeding. Otherwise, a belief that attempting to buy your way through will land you into even bigger problems will cause you to rethink your offer of a bribe.

As members of society, we sometimes mask corrupt a c t i v i t i e s u s i n g s o c i a l norms. We find ourselves in situations where bribery is disguised as a courtesy call to a community leader or chief whom one does not visit without some form of gift, metaphorically called a chicken. That is the prescription that almost all members of our society have for courtesy calls to chiefs or other decision makers from whom we are seeking help or business opportunities. Usually, this arises from the perceived frequency of a behaviour where we believe that everyone does it, or from a misplaced show of gratitude when injunctive norms convince us that it is appropriate to show gratitude when someone helps you.

That is how power ful a n d d a n g e ro u s s o c i a l norms can be. Coated in wider acceptability, they may not serve the public good. Therefore, beware of pluralistic ignorance – instances when we follow a particular norm because we falsely believe that everyone agrees with it. Of course a social norms approach has gained traction in anti-corruption interventions – but that is fodder for another day.