Children bear cyclone slap

Grief echoes in every corner of Bokosi Village in Phalombe District, hit hard by rockslides caused by Cyclone Freddy.

In the rubble of the deadly rockslides and flash floods from the neighbouring mountain, survivors liken the tragedy to the March 10 1991 disaster that killed over 700 people. They call it Napolo, a snaky trail of destruction left by gliding rocks and mud.

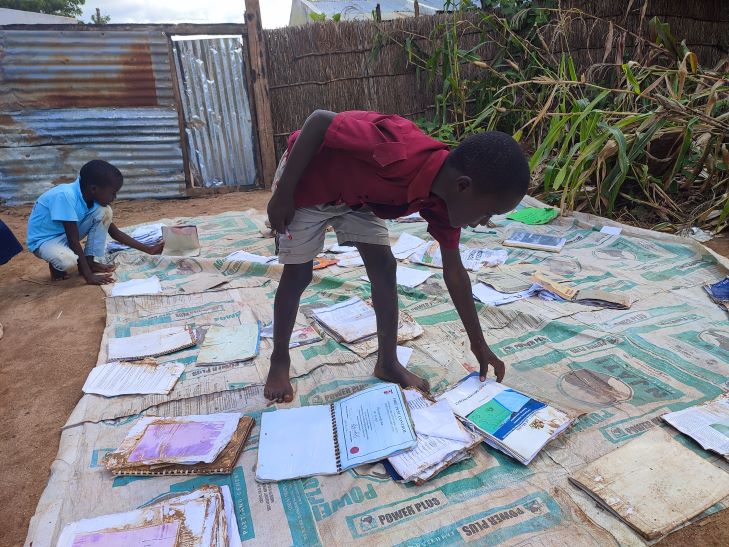

As sunshine returns to the devastated hillside setting, children are seen drying their schoolbooks in the sun.

“My education has been disturbed,” says Shaban Frank, 10. “I haven’t been to school since my grandfather’s house was destroyed by rocks 10 days ago.”

The Standard Four boy and his Standard Two sister Aisha lost their schoolbooks, clothes, pens and a school bag.

“This is all our grandfather picked from the damaged house,” Aisha points at the wrinkled, soaked books.

A rocky stream now splits the rubble of their rented home.

They stopped going to school two weeks earlier when the Ministry of Education suspended schooling for two days in response to torrents and early warnings.

The Department of Disaster Management Affairs (Dodma) estimates that the cyclone affected about 273 400 school children, with 133 of them confirmed dead and 586 teachers in 484 schools hit hard. However, campaigners says over 500 000 children in the affected districts across the Southern Region have been pushed out of school, with 390 schools housing the displaced survivors.

“When granny told me not to go to school, I didn’t know that I would stay home for weeks,” says Aisha, waiting for schools to reopen on March 17.

This mirrors the uncertainty of children stuck at home and in about 600 congested camps sheltering some of the 564 200 people rendered homeless.

On March 25, Dodma reported that Cyclone Freddy had claimed about 676 lives out of 600 000 affected people, with 1332 injured and 5373 missing.

The death toll is massive in settlements that mushroomed on ripped mountain slopes of Phalombe, Mulanje and Blantyre City.

More than 100 people have died in landslides on Soche Hill, which overlooks Manja and Naotcha primary schools. The count includes about 30 learners from Manja.

“The destruction is terrifying,” laments co-headteacher Isaac Chimenya. “The children who have lost their parents, siblings, friends and neighbours cannot concentrate on schoolwork while waiting to return to school,”

The school housed over 5000 displaced people from the devastated hillside.

“The number of learners killed will be known when schools reopen, but 26 children have been confirmed dead, with four hospitalised and some still missing. One teacher was swept by mudslides and another lost his home and everything in it,” Chimenya states.

This was the hill’s second mudslide in a decade.

President Lazarus Chakwera proclaimed a State of Disater and called for international support shortly after the Soche and Phalombe tragedies.

The overcrowded camp lack sanitation, privacy and peace of mind children require for schoolwork.

“The camps are congested, noisy and unhealthy for learners, who compete with adults for basics such as latrines, water and classrooms,” narrates co-headteacher Kate Chawinga.

The storm struck on the eve of end-of-term examinations for all classes, including mock tests for Standard Eight learners preparing for Primary School Leaving Certificate of Education examinations slated for May.

“With the crowd, noise and loitering, we cannot host the preparatory exams as planned. Certainly, the disruption will affect performance of children who are psychologically affected,” she explains.

Learners at play in the congested camps sound uncertain as learning did not fully resume on the announced dated.

Their teachers say schools require urgent support, including tents and plastic sheeting for temporary shelter, to resume teaching and learning.

“For children to reclaim their learning space, we need to move the displaced community from schools to open grounds or public halls in locations where they come from,” explains Chimenya.

President Chakwera appealed for international support for the displaced crowds vacate schools.

Unicef supports governments to provide lifesaving services to communities affected by humanitarian emergencies, including education, health, child protection as well as water, sanitation and hygiene.

Before the severe storm, it dispatched advance relief items to disaster-prone zones, including 50 tarpaulins and water buckets for the Shire Valley.

Manja camp chairperson Malinga Namuku says the displaced community wants to return home, but it will not be easy to rebuild their homes and livelihoods.

“We don’t want people to overstay here because our children require the same schools to enjoy their right to education and make their dreams come true, but we need support, including shelter so that we can move elsewhere,” he says.

His ward civil protection committee has isolated girls to sleep in women’s rooms to combat gender-based violence. n