Drug shortage worsens

Falesi Kalichero, from Katawa Township in Mzuzu, frequently runs short of blood due to sickle cell anaemia.

The girl regularly collects paraffin gauze from Mzuzu Central Hospital (MCH) for treating chronic leg ulcers triggered by her condition.

However, she has to pay an extra cost to buy the wound dressing from drug stores or bear the pain of hiccups in essential medical supplies.

“For some time, the largest hospital in the Northern Region does not stock the paraffin gauze and I am always advised to buy from private pharmacies,” says Kalichero.

She spends K3 500 on a pack of gauze.

“Sometimes my family doesn’t manage to buy the gauze and I use any cloth available at the time. This worsens the ulcers and the pain, “she says.

Similarly, Suzan Mzumara, a diabetis patient from Mchengautuwa Township in the city, repeatedly uses one needle to inject insulin into her bloodstream because replacements are long coming.

“It has become a norm for me to use the same needle for three or more days,” she states.

The struggles of Kalichero and Mzumara mirror the plight of many more other patients hit hard by shortage of essential medical supplies.

A snap survey by The Nation reveals that the drug stock-outs have worsened in public hospitals for the past three months.

Most hospitals have run out of insulin syringes and other diabetes medications, mental health medicines, hypertension, anti-rabies, painkillers, antibiotics, catheter bags, medicated plasters and anesthetic drugs, just to mention a few.

Rumphi, Karonga, Dowa, Bwaila, Dedza and Nkhata Bay district hospitals listed stock-outs of Diazepam, which is used in operation theatres to control convulsions; as well as drugs for hypertension, rabies and mental health.

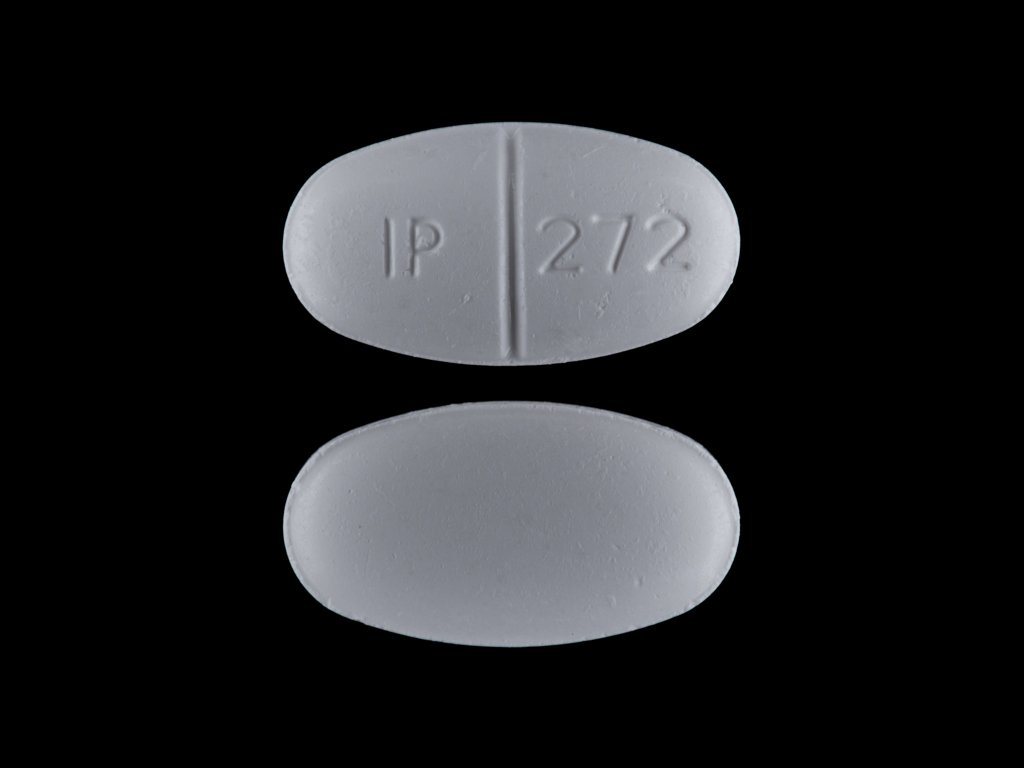

Also hard to find are simple antibiotics, including bactrim for people on HIV treatment as well as ceftriaxone and amoxil.

In an interview, Rumphi District Hospital spokesperson Bwanalori Mwamlima said the hospital does not have medicines for rabies, hypertension and asthma. Asthmatic persons require Salbutamol inhaler to calm breathing difficulties, but this too is lacking.

“We are also not doing well in stocks of mental health drugs,” said the publicist. “The hospital ordered the drugs from the Central Medical Stores Trust [CMST], which is yet to supply.”

On his part, Christopher Singini, spokesperson for Nkhata Bay District Hospital, said the situation “is getting worse” because CMST is not supplying the hospital’s orders.

His Mzimba North counterpart Lovemore Kawayi said his area only received its medical drugs and supplies last week.

Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital in Blantyre has not been spared. The country’s main referral facility does not have hypertension drugs, insulin syringes and a number of painkillers.

The situation is similar at other central hospitals, including MCH.

Health workers faced with patients at risk of dying from treatable conditions in district hospitals are advocating a shift to an old, partially decentralised system, where they could directly buy drugs from private suppliers.

Drug shortages in the country constitute an old phenomenon fuelled by mis-procurement, pilferage, misappropriation and logistical hiccups in the supply chain.

This time, fingers are pointing at CMST for allegedly failing to supply the district hospitals with drugs ordered.

CMST board chairperson Josiah Mayani admitted that there is a shortfall of drugs and vital medical supplies in the country.

However, he attributed the delay to the clearance and vetting process with other government agencies, especially the Public Procurement and Disposal of Assets Authority (PPDA), Government Contracting Unit and the Anti-Corruption Bureau.

Mayani said the public trust wrote PPDA last December, requesting a nod to procure the drugs that were in short supply.

He explained: “It took long for PPDA to grant us letters of no-objection to procure drugs and supplies. It was only granted in April or May.

“The delay created a gap in the supply chain. This is why there was big shortage of drugs and medical supplies in our health facilities in June and July. So it isn’t right that CMST has failed, no, but the process.”

However, Mayani offers a ray of hope as some drugs have been trickling in. He reckons the situation might return to normal by October.

“We have been meeting the directors of health services in districts who have been complaining and advocating for partial decentralisation of the [procurement system] so they can be getting some supplies and drugs from private suppliers, a system which was abused in the past,” he said.

Mayani appealed for recapitalisation of CMST, which owes suppliers about K17 billion.

“We can’t operate without money. Even our suppliers complain that we want more drugs and medical supplies from them, yet we owe them a lot,” he said.

Mayani said CMST needs to fix internal lapses discipline errant officers.

Acknowledging the hiccups in the provision of essential drugs and medical supplies, Ministry of Health spokesperson Adrian Chikumbe said policymakers are now discussing a short-term measure to authorise district health offices to use part of their budget to procure drugs from private suppliers when CMST fails.

“Because we are talking about policy change, it can’t happen overnight. We have to look at the pros and cons,” he said.

As a long-term strategy, the Ministry of Health is lobbying Treasury to allocate at least 15 percent of the national budget to health care spending in line with the Abuja Declaration.

Currently, the budget for medicine hovers around K20 billion, excluding donor-aided consignments such as anti-malarial medicines, anti-retroviral therapy and Tuberculosis pills.