When monkeys drink from people’s cup

Ordinary talk rarely brings extraordinary results. People of Chimbotera Village in Traditional Authority (T/A) Kampingo Sibande in Mzimba writhe in this painful certainty every time they hear power holders say the same old things about access to safe water.

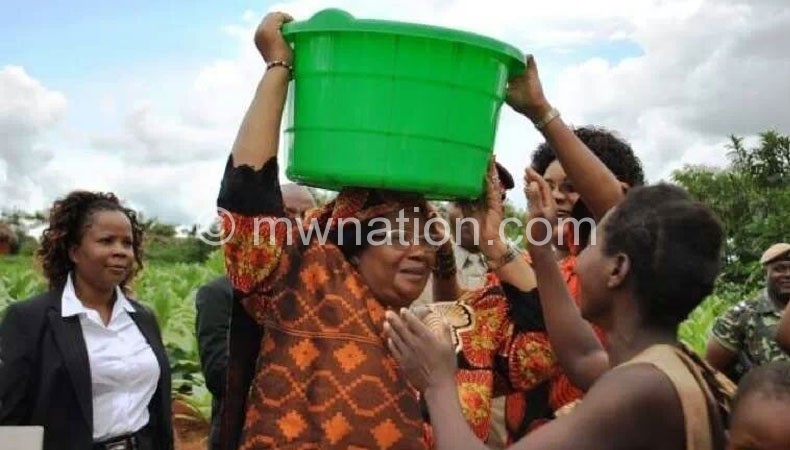

What constitutes ordinary talk? This question seems inevitable unless you follow how President Joyce Banda has added drawing and carrying buckets of water to her job description or political campaign since she visited a 16-million litre tank at Mbavi Air Wing in Lilongwe early this month.

Watered down by heavy rains landing at the old air strip in T/A Njewa, the President’s brief address had two highlights: First, “water is life”. Second, “it is possible for government to give rural Malawians access to safe water.”

And the first citizens declared: “It is my duty as the President to ensure people have good water.”

But tucked in their remote locality in Mzimba, the people of Chimbotera, Zulu and Yiwombe localities have heard this several times. As politicians sound determined to make provision of clean water part of the national agenda in the run-up to the May 20 Tripartite Elections, the underserved communities want decision-makers to close the widening gap between talk and long-awaited action that will give them a break from relying on untreated water from risky sources.

“If water is really life, why is government failing to give us reliable sources of safe water?” asked Suya Yiombe, whose wife wakes up around 5am in search of the life-sustaining liquid.

Located along the M1 road, his community is no usual sight. Moving over hills and valleys in the rural setting, visitors will be stunned by lack of boreholes, taps and other secure forms of water.

However, the scarcity of safe water silently threatening lives in the remote community springs to life on a sunny day.

Plying on the road between Mzuzu and Mzimba, observant travellers are usually taken aback by water slowly dripping from massive rocks into buckets, jerry cans and other vessels that lie under nobody’s watch on the roadside.

Some even wonder what the supposedly carefree owners of the vessels are up to.

“But these are our taps, our most reliable source of water,” said Mary Jere, 29, re-adjusting a waterproof piece of Chibuku opaque beer packet which is attached to the giant rock to serve as a tap.

The mother of three explains: “During the dry season, we rely on Matchabwada stream. When the rains start, the water becomes too muddy and sometimes floods. That is why the roadside fountains become handy when the rains start.”

Such is the order of life between December and May.

Yet, the water that looks colourless is not without blemish.

Locals say the unprotected water source and slightly over an hour it takes to fill a 20-litre bucket means monkeys drink from their vessels. The clever ones use jerry cans to keep away the untamed intruders.

During the visit to the rocky fountains, the monkeys were spotted sipping water from the buckets before they vanished into stumps and remnants of pine trees that once formed a thick part of Viphya Plantation, popularly known as Chikangawa.

This experience may not be different from the streams where people share water pools with cows and goats, but it raises questions about how government is using its claimed ability to provide water for the unreached masses.

Oral history in the village has it that the ‘taps’ on the rocks came into being in 1999 when government was modernising the M1 Road, the country’s longest tarmac. The openings largely constitute holes drilled when the road’s constructors were blasting the rock-strewn terrain.

The water may well be hazardous for their health, villagers fear.

“Until 2004, engineers and government officials used to come to warn us to stop drinking the water because they said it contains poisonous substances,” said Selina Msimuko.

During the interview, the locals kept pointing at a stone wall with a white spot where the toxic substances were supposedly listed. The writing on the wall has faded with time. None of it makes sense any more. So does the fear for the life-threatening trickles meant to be a no-go zone for the villagers.

“We still drink this water because we have no alternative source,” said Msimuko.

In the reasoning of former Mzimba district commissioner Reverend Moses Chimphepo, such problems could be of the community’s making. He said before amplifying their cries, the media and onlookers need to interrogate how the so-called victims of underdevelopment ended up in the underserved localities.

“There are times people leave designated settlements which have enough water sources, schools, roads and hospitals to live in a hard-to-reach areas where providing these services is not only costly but also not feasible,” said Chimphepo when asked about the district’s development challenges.

Following Msimuko’s footsteps as she staggered with a jerry can of water on her head, a glimpse of the affected households came into view. It is a cluster of predominantly glass-thatched huts made of residual timber alternatively known as vigwagwa.

The settlement is located near the tarmac which splits Viphya Plantations, the country’s largest timber producer, between Nkhata Bay and Mzimba. The temporary huts are a common sight along the motorway.

But what forced Msimuko and company to opt for the ‘waterless’ spot of all places in the vast district?

When asked, the woman said: “Slightly over five years ago, we relocated from our villages to do business here. With people from all parts of the country and beyond the borders harvesting timber in the forest, we needed to find ways to tap from the opportunities this increased activity presents.”

So, the hamlet joining the fray of people cashing in on the booming timber business in the Northern Region could be a personification of how rapidly growing population is compounding poor access to water and business openings.

Looking around, the emerging spirit of entrepreneurship is unmistakable. The newer settlements Chimbotera residents prefer to call Bengende—meaning ‘literally naked’—are carving a niche with stalls that hawk liquor, soap and manufactured foodstuffs to sawyers and other timber businesspeople that throng Chikangawa.

Here, the timber-making industry sometimes leaves married women unceremoniously single as their husbands increasingly disappear into the pine plantation to take up jobs as sawyers and porters. Narrating how her man left her in a similar fashion a year ago, one of the ‘single mothers’ feared for her children as some of them have ended up being hit by cars as they go to fetch water on the roadside rocks.

The residents say the stretch is prone to road accidents with cars overturning every month. Near the village, a road sign urges road users to slow down because speed kills.

Demonstrating that the audacious race for business opportunities does not make poor access to treated water a problem of their making, what Yiwombe and company call “our biggest problem” cuts across the hilly terrain to Zulu, Yiombe and the villages where they once lived.

How many people suffered diarrhoea or any other waterborne disease in the recent past?

Jere responds: “We don’t count anymore because diarrhoea has become part of life.”

But as their wait for a better deal continues, the communities wish leaders had always implemented what President Banda repeated at Mbavi Air Wing: It is the duty of leaders to ensure people have access to water.

And one dare add that not just water, but clean and treated water—the safe sips every Malawian deserves as the world counts down to the deadline of the globally accepted Millennium Development Goals.

In a budget analysis titled ‘Water Sector: A Marginalised Priority ‘, Water and Sanitation Network (Wes Network) says more needs to be done although the country has been rated on track to achieve MDG targets on water and sanitation.

The areas that need fixing are well-documented in water sector assessments and Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) and numerous other indicators the country has been churning out over the years.

In 2010, the DHS showed that between 65 and 75 percent of the country’s population have access to improved water and sanitation. This means slightly over four million of 15.5 Malawian have no access to health sources of water.

The roadside community, like those scattered in their hills and valleys where their original homes lie, belong to the unreached quarter of the population.

Their cry? Water is life and should not just be a catchphrase for hoodwinking voters.

The road the Bengendes travel, whether the tarmac to the fountain on the rocks or pathways down the steep slopes to Matchabwatchabwa Stream, is a living testimony that water is life.

Interestingly, they seem to know that every system, society, government and institution must endeavour to protect and promote the right to life—that the right to water must be jealously guarded, relentlessly championed and adequately funded.

Wallowing in their cry, the glaring question as the country grapples to overcome pitfalls in ensuring universal access to clean and safe drinking water is about financing to the life-saving sector.