Malawi still at crossroads: part 2

Twenty-five years ago, a young enthusiastic economist graduated from Oxford University. No sooner had he returned home to Blantyre, Malawi than he began writing regularly on the economy in Weekend Nation, a sister publication to this newspaper, trying to understand the root causes of Malawi’s underperformance.

One of the first articles was entitled ‘Depreciation, inflation and trepidation’. The article began in this way: “You don’t need an economist to tell you that rising prices of goods and services coupled with a falling currency is bad news”*.

Let me apologise for the young economist because he was long-winded and failed to convey the basic principles of economics. That is the problem with economists, they can’t communicate like politicians! So let me recall the words of that economist.

What is inflation

“Inflation is the persistent rise in prices of domestic goods and services. It can be split into a food and a non-food component. Food inflation has declined due to good harvests, but non-food inflation has been persistently high partly due to the depreciation of the kwacha. A currency is said to depreciate when forces of supply and demand cause it to lose value against foreign currencies. This is different from devaluation when the loss in value is due to the intentional action of the Reserve Bank of Malawi (RBM). The actions of RBM can play a central role in determining inflation and the value of the kwacha. The key question is whether the Bank can do anything to stabilise the current situation”*.

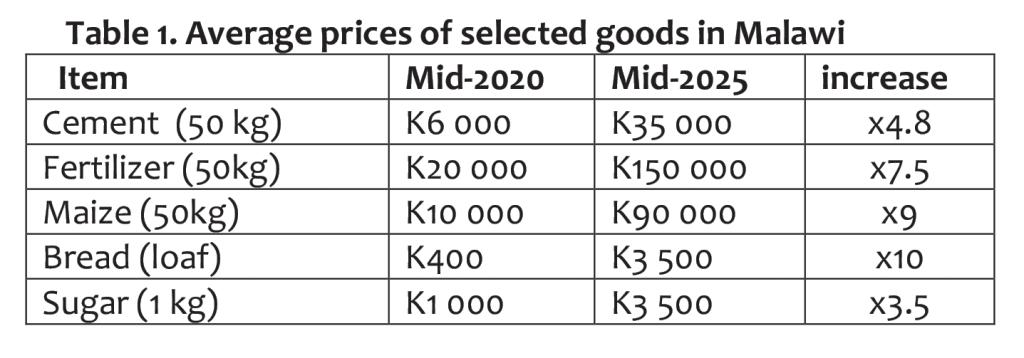

This is a standard explanation highlighting “food inflation” and “non-food inflation”. In Malawi, the months after harvest (April to June) would normally see food inflation abating, then rising during the lean months (October to December). This trend has held consistently over the years except when we have had a bad harvest. However, in the past five years, inflation has been galloping ahead even after the harvest pointing to the persistence of non-food inflation, and as stated above, the role of the central bank which recently celebrated its 60th anniversary and, thus, has lots of historical data to understand the key drivers of inflation.

What is the role of the central bank?

As the centre of monetary policy, the central bank should fight inflation, period. Meaning it should keep it low, ideally below 10 percent. The article cited above continued to explain the ways in which our economy is buffeted by shocks:

“Inflation is driven by both internal and external shocks. External shocks include sharp increases in the price of key imports such as the price of crude oil. There is not much we can do about this. Internal shocks include droughts which would push up food inflation. The RBM’s monetary policy is another possible source of inflationary pressures. This occurs when there is excessive expansion of the money stock and of credit. Put another way, when there is too much money chasing too few goods in the economy, prices go up. While it is not technically accurate, we can think of the money creation process as one where the Reserve Bank of Malawi is “printing money”*.

The young economist should have been more emphatic on this point. If the central bank increases the money supply faster than economic output is growing, inflation will occur (in the absence of other measures). Printing too much money causes inflation, and if this persists, the money can become worthless. The purchasing power and value of the money fall sharply. Taken to extreme, this can result in hyperinflation, something we should avoid because the effects will be devastating for the poor.

Speaking rhetorically, the young economist asked: “Why would the bank print money excessively?”*. In classic Socratic fashion, he answered: “Typically, the main culprit is government budget deficits. When the government is failing to cover its expenses, they can borrow money from the private sector as well as from the Reserve Bank. Borrowing from the Reserve Bank is equivalent to printing money which expands the money supply. This is considered loose monetary policy which if pursued in excess will result in inflation”*.

According to the World Bank, money supply growth in Malawi has been elevated over the period 2020 to 2025. Specifically, the money supply growth was reported at 47 percent year-on-year in April 2024, driven partly by financing of the fiscal deficit by RBM) By February 2025, money supply growth remained high at around 37.8 percent, also driven by high deficit financing. The rapid growth of money supply has contributed to persistent high inflation and macroeconomic instability.

We return one last time to our young economist, who recommended as follows: “To reduce inflation and stabilise the kwacha, we need to focus on the internal factors that we can control. For inflation, this means following prudent fiscal and monetary policies. This is the economist’s jargon for telling governments to live within their means so that they don’t resort to borrowing from the Reserve Bank or borrowing excessively from the private sector. In short, we need to reduce the budget deficit! On the revenue side, it would seem that government has made major progress. However, one wonders whether the expenditure side is being adequately controlled or whether the government’s scarce resources are even being utilised effectively”*.

From Part 1 of this series published on this very page last Thursday, we know already that Malawi’s fiscal deficit has been very high, in excess of nine percent of gross domestic product (GDP). It is a full-blown fiscal crisis; literally the worst deficit across Africa. I wonder what the young economist would think about that.

Things fall apart

The words I wrote 25 years ago still hold true today. This has nothing to do with politics. It is about the fundamental principles of economics and how policy affects people’s lives. Inflation hurts the poor most because they have no buffers or savings. Even the wealthy suffer because their pensions would be wiped out by hyperinflation. Your hard earned savings may become worthless due to inconsistent policy implementation.

What I have learned in 25 years of watching this economy is that our politics always dominates and drowns out all other voices. Let me be clear:

Over the 2020 to 2025 period, Malawi has experienced very high money supply growth, often in the range of 38 to 47 percent annually, largely fuelled by fiscal deficit financing and monetary expansion. This monetary expansion has been a key factor behind Malawi’s macroeconomic challenges between 2020 and 2025.

While food price inflation has played a role, the main drivers of inflation have been:

Fiscal deficit financing: Large fiscal deficits, which increased steadily to almost 11 percent of GDP by 2023/24. RBM financed these deficits, injecting more money into circulation.

Loose fiscal and monetary policies: The government’s responses to external shocks and the lack of tighter monetary policy underpinned continued monetary expansion.

External shocks and climate events: Numerous external shocks worsened economic conditions leading to increased government spending and monetary accommodation.

Our present crisis reminds me of Chinua Achebe’s famous novel, Things Fall Apart. The title comes from a lesser known line from W.B. Yeats’ poem The Second Coming. Yeat’s line is more apt to our deepening crisis: “Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold”.

NOTE: All quotes cited from “Development Matters: Malawi at the Crossroads” by Taz Chaponda (2013). Feedback welcome on chaponda@hotmail.com