Is universal subsidy possible in Malawi?

Over the past 15 years, the Farm Input Subsidy Programme (Fisp), a programme that was designed to ease access to farm inputs, has dominated the agriculture and food security discourse in Malawi.

Since the dawn of multiparty democracy in 1994, access to food has been the central feature of almost all the political contestations and as a matter of fact, all governments elected in the multiparty era after 1994 have been elected based on their promise to guarantee food security to the electorate.

The evidence of politicisation was evident from the initial multiparty era subsidy programmes like the Starter Pack in 1996, which became a flagship programme for the United Democratic Front (UDF) government. The Fisp was firstly announced on a political rally and its success over the subsequent years, helped president Bingu Wa Mutharika have a majority vote in 2008.

The political importance of the Fisp has also been evident in the fact that governments in Malawi, which are notorious of discontinuing all development programmes initiated by the previous administration, have always spared the Fisp that has now transcended three administrations without a major reform and departure from the initial programme of 2004.

Subsidies have been part of Malawi agriculture landscape for a number of years. Since the first direct subsidy for African smallholder farmers was introduced on native trust land in 1951, mainly for tobacco farmers, subsidies have dominated Malawi agriculture production.

As matter of fact, our agriculture has never survived without a subsidy of some kind on agriculture inputs to the extent that both inputs and output markets were heavily subsidised throughout the 1970s and 1980s through the Agricultural Development and Marketing Corporation (Admarc).

Despite the attempts to have the subsidies removed under the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank’s Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP), subsidies on agriculture have remained. Subsidies have been phased out and reappeared.

For instance, after a zero subsidy in 1994, they re-emerged in 1996, in form of a Starter Pack that was given to every smallholder farmer for two years before the programme was changed to Targeted Input Program (TIP). However in 2004, Malawi re-introduced a full subsidy programme in Fisp.

The programme was a complete departure and a reversal of its commitment under the SAP. The introduction of the Fisp was initially criticised by several donor agencies that believe in neo-liberal tendencies and the ‘power’ of the market. However most of these donor agencies joined the fold in supporting the programme after noting its instant success and also the stubbornness of Bingu to continue with the programme no matter what.

The government as a duty bearer and also access to food being a human right, felt obliged to provide agriculture production assists and reintroduced a full subsidy programme following the 2000/2001 food crisis, which came despite the presence of other productivity support programs like TIP and APIP.

The food crisis, of course, resulted from a combination of factors that included the drought and the mismanagement of the strategic grain reserves but production failure as a result of degraded soils was thought to be the main reason for the situation. This, therefore, meant that an increased use of fertiliser and improved crop varieties (hybrids) by the smallholder farmers could solve this problem in the short to medium-term.

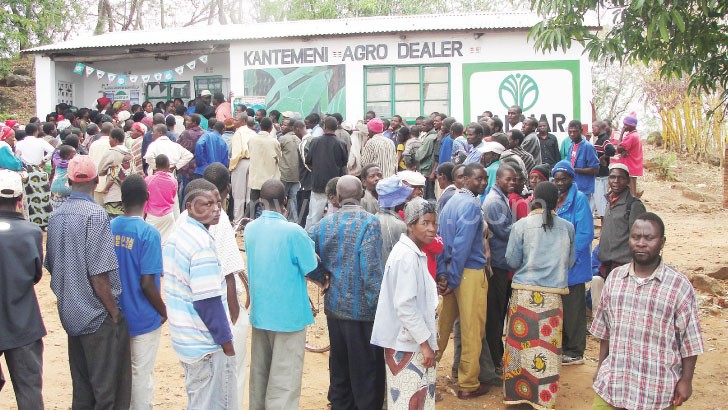

However, the main reason why most smallholder farmers, who are the main food producers in Malawi, were not using fertiliser, was the cost of the commodity on the market. High levels of poverty and long distances to find fertiliser made access a more difficult thing. Farmers were unable to procure at the market price; hence, the need for government support.

The subsidy programme was further justified in the sense that the cost of importing one metric tonne (MT) of maize during the 2000/2001 food crisis was three times as much as the cost of producing the same tonne under subsidy. As such it was much cheaper to subsidise production than to import food and at the same time delays that occur during importations could exacerbate a food crisis as opposed to having the maize within the country through local production.

Coupled with good climatic conditions, the Fisp was an instant hit and a darling for the farming communities. In its first year, Malawi had a surplus maize production of about 200 000 MT for the first time in about 10 years. The production surplus was maintained for a number years averaging around 1.5 million MT per year.

The benefits from the Fisp spilled over to other sectors like education, where pupil enrolment in schools increased, incidences of child labour reduced and also a good reduction in hunger related diseases and death.

Over the same period, Malawi experienced an unprecedented economic growth of around 7 percent, with a much reduced inflation. Over the years since its introduction, the Fisp has become part of the Malawi’s production system.

Calls to end the programme due to several challenges it has been facing have always fallen on deaf ears and despite these challenges there is no end in sight for Fisp. Calls on farmers to graduate either are bearing no fruit as the programme has lacked the transformative drive that can warrant farmers to graduate without them falling back into hunger. As such Fisp has been fully accepted as the necessary evil that we must learn to live with.

However one of the contentious issues of late in the Fisp has been whether we should continue with the current smart subsidy format of targeting through coupons or we should go universal. This debate has also found its way into the current presidential campaigning with some prospective candidates promising to phase out the targeting criteria and turn the program universal. The question that we have is whether Malawi has the capacity to implement and maintain a universal subsidy and what lessons we can learn from other countries that attempted a universal subsidy.

It has to be noted that the main reason why Starter Pack was turned into TIP and also why Fisp is currently a targeted programme is the cost of managing and maintaining such a huge programme.

Currently the Fisp, as of last year costed about K40 billion, targeting about 1.5 million smallholder farmers. This means roughly that if could we go universal at the current terms of the subsidy and making the subsidy only available to all eligible smallholder farmers, whose current figure ranges around 5 million, the cost of the programme could be around K133 billion. This means that the Fisp alone could cost slightly higher than the current funding to the entire Ministry of Agriculture.

Targeting was also made necessary to avoid leakage of the inputs to the estates sector, which is not supposed to be part of the subsidy programme as it is seen to have the economic capability to buy at the market prices. Leakage may not only be to the estate sector but also across the borders, without proper targeting and policing mechanisms, Malawi may end up subsidising farmers from neighboring countries.

At the same time, Fisp had a special objective of ensuring that Malawi is self-sufficient in food and it became the means of achieving household food security, as such only those vulnerable to hunger have to be supported with inputs.

Estates do not mostly produce food crops as such were outside of this objective. Additionally, it was also felt that universalism could limit access to fertiliser by the smallholder farmers, who are currently struggling to buy at the current subsidised price. Government could not have managed to subsidise universally to the level that a poor smallholder farmer should be able to buy before the rich estate and capitalist farmers and opportunistic traders clear off the market.

However, the implementation lapses over the years, have made it that leakage of inputs has become so rampant and also poor monitoring of the programme has resulted in the eligible beneficiaries not benefiting from the currently targeted programme. These have justified the calls from other stakeholders that the programme should be phased out, while some are proposing for a universal programme, which could also ease the social tension that comes with targeting.

Universal subsidy is possible, however we may need to firstly appreciate the challenges listed about above. In many successful late industrialising countries, it became self-evident that where poverty was widespread, targeting would be unnecessary and administratively costly.

Thus the universalism in many countries was in fact dictated by underdevelopment and widespread poverty. Targeting was simply too demanding in terms of available skills and administrative capacity. This is also currently the state of affairs in Malawi, especially among the food producing smallholder farmers, who are too numerous for any targeting techniques to effectively work.

However, if we desire to depart from the current format of targeting and go universal despite the challenges that may be associated with it, I have a few suggestions I would like to put forward in designing what I feel could be a cost effective programme. As such in the next article next week, I will present my thoughts in the institutional and structural design we may need to take with a universal subsidy that I feel could be politically viable and economically sensible. n

*Tamani Nkhono-Mvula is an expert of agricultural policy and development.