Malavi tragic crash

Twenty five years ago, a passenger train from Limbe in Blantyre to Makhanga in Nsanje crashed after losing brakes soon after departing Malavi Trading Centre.

During the perilous downslope journey on May 6 1998, the train, carrying 250 passengers and crew, killed 18 people and severely injured 100 others.

Former president Bakili Muluzi instantly appointed a commission of inquiry headed by retired Judge Duncan Tambala, which found Malawi Railways Limited guilty of negligently permitting a train with faulty brakes to operate.

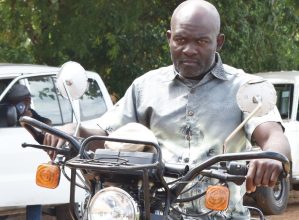

Locomotive driver Mesis Yamweka Munthali, 66, was accompanied by two engineers on the fateful trip. Recounting the ordeal in an interview at his home in Limbe’s Railways location Munthali, who was aged 41 at the time of the accident, feels lucky that he has lived to this day to tell his story.

He narrates: “When my bosses assigned me the passenger train to Nsanje in the Shire Valley, the locomotive had stayed for two years under reconstruction.”

“I don’t know how they came up with this idea, but they were eager to have the train showcased to the public, unfortunately, with passengers on board.”

However, the locomotive D-E 519’s reconstruction was not fully completed.

“The junior engineers warned their bosses of the potential dangers, but the locomotive was still set to carry the passengers,” says Munthali.

He says two other drivers took the train for a test run on the eve of the ill-fated journey and noticed that it was not performing efficiently.

He recalls: “When I reported for work the next day, the train was already set to depart.

“Entering the cabin, I ran a quick check on the gauges and all readings cleared normal. The most peculiar thing I found before the departure was the two engineers that were sent to accompany me to take note of the train’s performance.”

The train to Makhanga set off to hit the maximum speed of 25 kilometres (km) per hour, as the small rails could not handle higher speeds.

“The locomotive would derail if the required velocity was surpassed,” he explains.

Approaching 15km per hour, about 200 meters from the station, he checked the brakes and, to his surprise, they did not respond.

“The locomotive had five brakes. They included air brake, vacuum brake, emergency brake and handbrake, all gave no response to slow the train as we gained speed,” he recalls.

Distraught, he alerted the engineers, hoping they would solve the problem, but they did not seem to figure out a way to stop the train.

The crew hoped the train would slow down as it went uphill just after Admarc offices in Bangwe Township, but it continued accelerating down slope.

The crew alerted passengers about the looming disaster, blowing the whistle to warn people and animals to flee from the railway.

“At that point, we had already lost all hope and knew quiet well that our journey would come to an end over the bridge ahead of us,” he says.

But they made it through, much to the relief of both passengers and the crews. Yet the battle for survival had just begun.

“The engineers huddled together in the space between the cabin’s two driving desks as the locomotive was now clocking over 25km per hour.

“When the bogie wheels connected by chains sprung out of place, the locomotive leaped off the rails and off we went—the compartments screeching on top of each other as they slid along. The only thing I heard was a snapping sound.”

When the tossing stopped, Muthali smelt “blood amid desperate wails from outside”.

“I was thrown to the ground,” he recalls. “I soon lifted myself up, but could not check on the passengers because I was gripped by the fear of being blamed for the accident.”

The survivor raced back to Limbe Station for some help. On the way, he noticed the flow of blood from his wounded leg, arm and head. He fell to the ground, says the veteran driver.

To his luck, someone came to his rescue, putting him on a bike to Chikunda Police Unit where they boarded a bus to Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital in Blantyre.

“Moments after,” says Munthali, “the hospital was bustling with casualties with bloodstained clothes, broken backs and severed limbs from the wrecked train.”

Inconceivable pain echoed in the hallways and walls of the Southern Region’s referral hospital.

Munthali spent two weeks in hospital. Then his first child was 15 years old and in Standard eight.

The train driver says he felt relieved when Muluzi commissioned the inquiry. After his full recovery, the inquiry found him not guilty.

Looking back, he says: “Their experiment cost the lives of others and almost mine. Some were left scarred and disabled for life.

“The grief cuts deep for my friends who lost their lives on that tragic day. Every day and night I utter a silent prayer to the souls of the departed,” he says.

Muluzi ordered the State-owned train operator to compensate the casualties of the fatal accident.

“From the report, there is no doubt that Malawi Railways is at fault. Somebody was just careless,” said Muluzi.

The presidential decree relieved the survivors who were battling for compensation.

“It is good that, finally, justice will be done. We lost a lot of property in that accident on top of footing hospital bills for a cousin of mine who sustained serious injuries,” said Blantyre resident Moses Kamwendo.