Malawi still at the crossroads—part 4

A picture worth a thousand words

As we near the end of this five part series, a reminder of what we have seen so far and why the upcoming September 16 General Election is so important for economic governance. Whoever wins will have to contend with a declining economy. It is striking that the trends shown below are all moving in the wrong direction! Why is this happening? The subtitles tell the story.

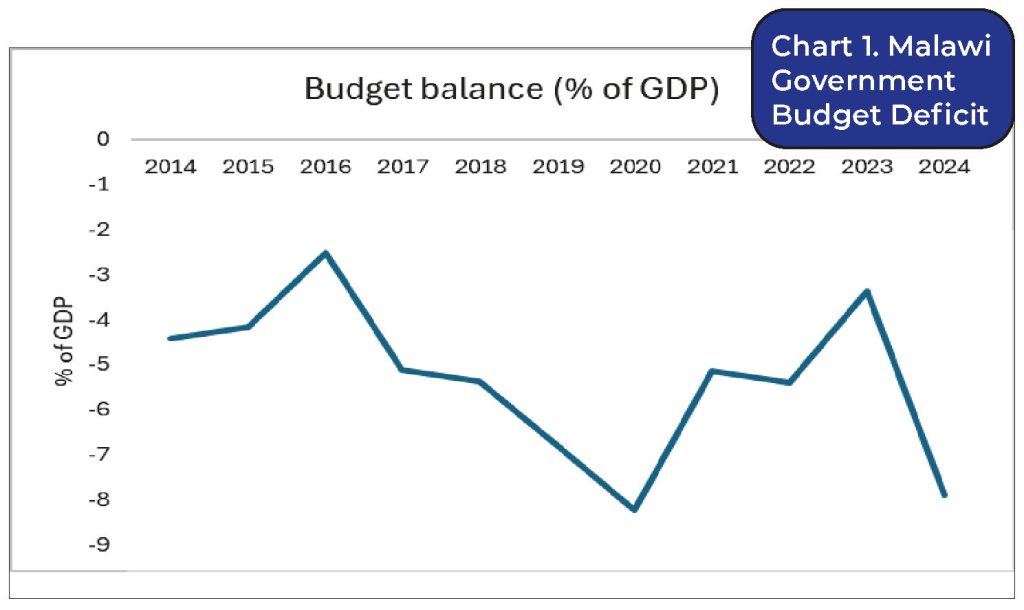

Budget deficit is increasing

A budget deficit, also referred to as the “fiscal deficit” occurs when a government spends more money than it earns from taxes and other income.

Chart 1 shows that Malawi has had a budget deficit every year for the past decade.

In 2014, the deficit was about four percent of gross domestic product (GDP)*, which means the government was spending four percent more than it earned. There was some improvement in 2016, when the gap narrowed to about 2.5 percent of GDP. After that, the situation worsened. From 2017 onwards, the deficit grew, reaching nearly nine percent of GDP in 2020, likely due to extra spending during Covid-19 and lower revenues.

Although there was a brief improvement in 2021-2023, the deficit widened sharply again in 2024 to around eight percent. All indications point to a deficit greater than 10 percent in 2025, which is more than double the average deficit of the Southern African Development Community (Sadc) region.

Running big deficits for many years means the government borrows more, which increases debt and interest payments. This leaves less money for schools, hospitals and roads. As the deficit continues to grow, it weakens government finances and the Treasury resorts to more borrowing to cover the deficit.

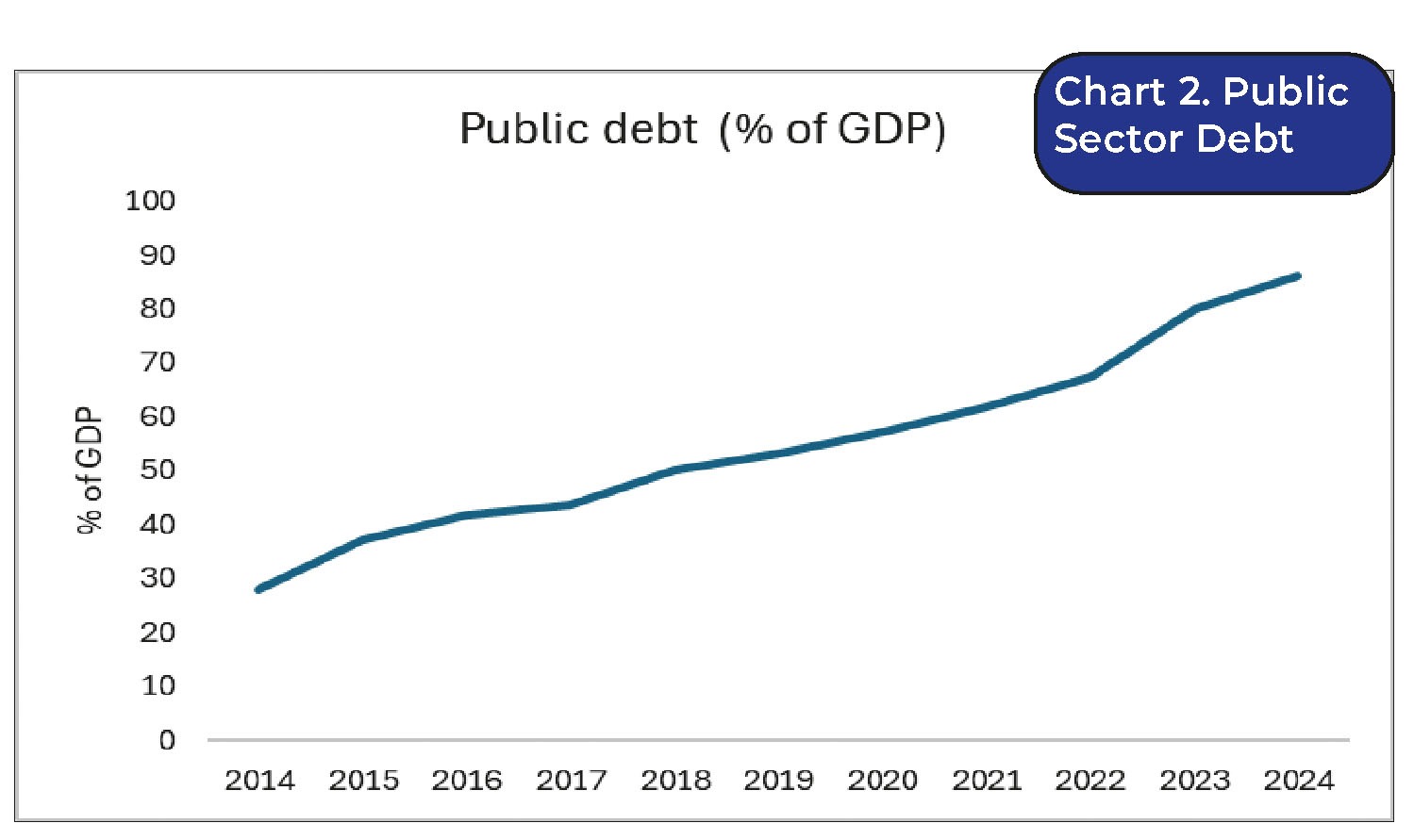

Consequently, public debt is growing

Public debt is the total amount of money that a government owes to lenders. This can include borrowing from within the country and from other countries or international institutions such as regional banks. Governments usually borrow when their spending is higher than the money they collect in taxes and other income.

Chart 2 shows that Malawi’s public debt has gone up sharply over the past 10 years.

In 2014, debt was about 30 percent of GDP. It increased steadily every year, passing 50 percent in 2018 and 60 percent by 2020. The rise became even faster after 2020 and by 2023 debt was around 80 percent of GDP, reaching about 87 percent in 2024.

When government debt grows too much, the government has to spend more on paying interest instead of funding services like schools, hospitals, and roads. It can also lead to higher taxes in the future and make it harder for the country to borrow money at low cost. If the trend continues, Malawi could face serious financial stress, including a debt default which would harm our reputation internationally.

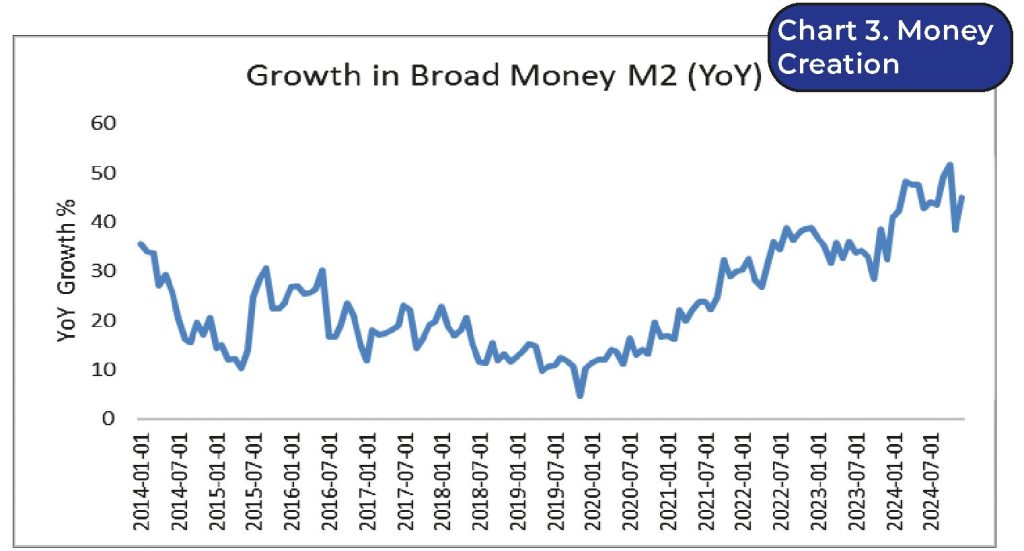

What has contributed to money creation?

Money creation by the central bank is the process by which the Reserve Bank of Malawi (RBM) increases the total money supply in the economy, typically by issuing new local currency or by expanding bank reserves, which enables commercial banks to lend more money. This increases the overall liquidity in the financial system.

Typically, central banks create money digitally by increasing reserves in the banking system, for example by buying government bonds such as Treasury bills). Through such actions, RBM has expanded money supply or M2. This is equivalent to printing money and is a major source of inflation which has been running above 25 percent annually. (See Chart 3)

Malawi has witnessed rapid growth in broad money (M2) in recent years primarily due to an increase in the total amount of cash and cash equivalents circulating in the economy. The rapid increase in M2, which grew by nearly 47.8 percent in early 2024, creates inflationary pressures. Money creation is linked to the government’s spending decisions and specifically to the persistent government deficits shown above in Chart 1.

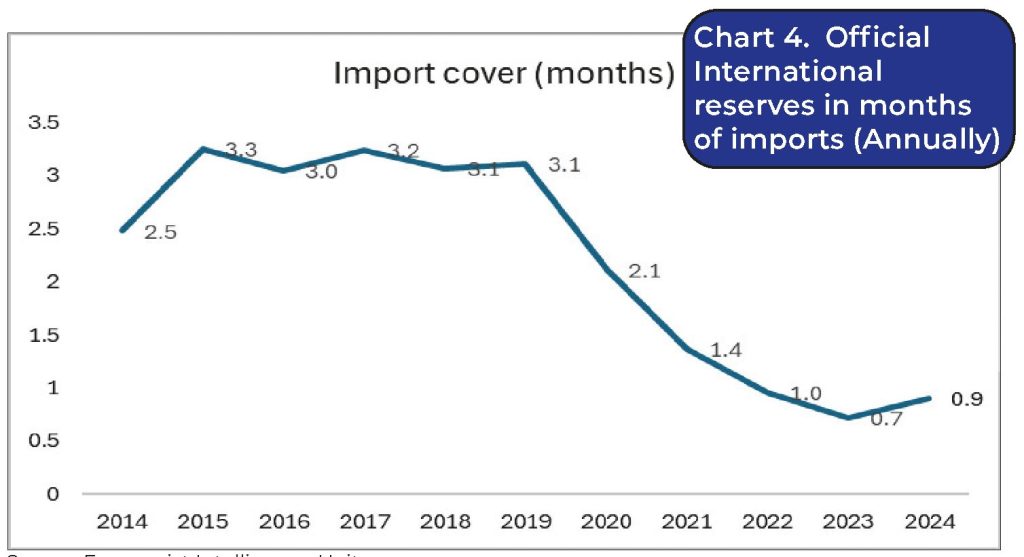

While forex reserves have dwindled

International or foreign reserves are the readily available foreign currency, gold and other assets held by RBM to ensure financial stability, finance balance of payments needs, and influence the exchange rate. In our current fixed exchange rate system, reserves are used to maintain the pegged currency value. Thus, if demand for Malawi kwacha is high, reserves increase, but if demand falls, RBM sells reserves to support the currency, thus depleting them.

If the economy is weak or slowing down, we see a strong outflow of capital or declining demand for the kwacha. Due to falling demand for the kwacha, RBM must sell its foreign currency reserves to buy the kwacha and prevent its depreciation. This directly reduces the country’s international reserves shown below. (See Chart 4).

International reserves have declined sharply in recent years due to a combination of weak exports base, a large import bill for essential goods like fuel and fertiliser, dwindling foreign aid, and increased debt servicing costs (in dollars). These factors have created a significant foreign exchange shortage, making it difficult to import necessary goods, stifling economic growth, and leaving the country with limited buffers against external shocks (which are bound to occur from time to time).

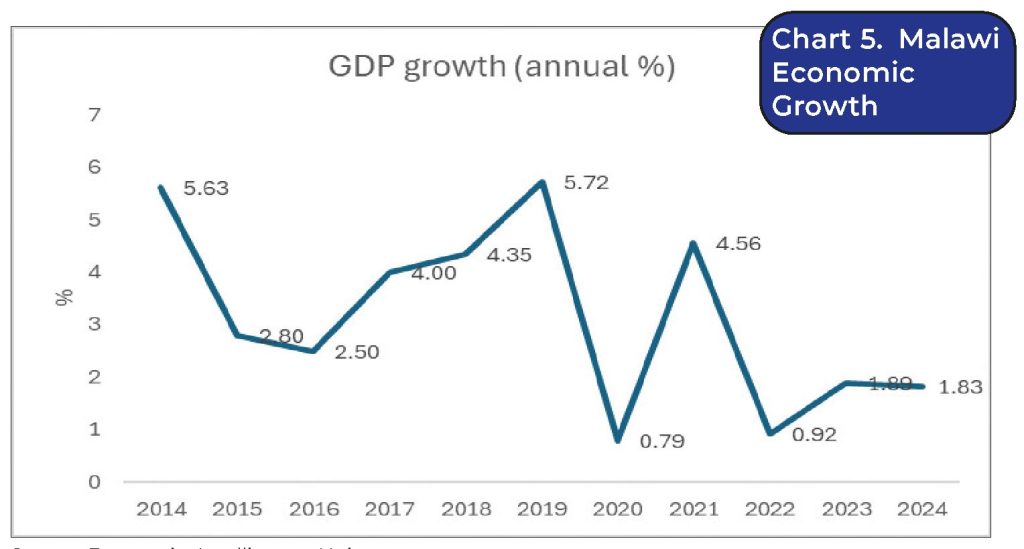

And economic growth has virtually collapsed

Our economy has been buffeted by numerous shocks including cyclones, Covid-19 and droughts. However, the economic collapse we are witnessing today was not the only possible outcome. Failure to implement sensible public policies weakened our “shock absorbers” (or economic buffers). The fixed exchange rate has depleted forex reserves, while excessive spending and borrowing by the government is causing economic damage.

In terms of growth, the highest growth was in 2019 at 5.72 percent. In 2020, there was a big drop to 0.79 percent, showing that the economy almost stopped growing. This was due to Covid-19 and related challenges. Thereafter, the economy bounced back in 2021 (4.56 percent), but then dropped sharply again in 2022. From 2023 to 2024, growth stayed very low, around 1.8 percent. With the current forex shortages and high inflation, growth for 2025 is likely to fall back to 2.0 percent—a stagnant economy. (See Chart 5).

Poor economic management has led to very low growth and high inflation, a bad combination which leads to slower job creation as low growth means fewer jobs and business opportunities. We also see rising poverty as overall national incomes falls. Low growth also puts pressure on government as it collects less tax, making it harder to pay for health, education, and infrastructure. And finally, weak growth amidst high inflation is associated with a higher cost of living making life harder for the poor who make up 70 percent of the population. One wonders how they will vote?

*Taz Chaponda is a senior economist who has worked for Mastercard Foundation, the IMF and the World Bank. He was budget director in South Africa and the managing director for Malawi Agriculture and Industrial Investment Corporation. He has degrees from Harvard University and the University of Oxford, and an MBA from INSEAD Business School