Sexual violence stuns Mzimba

It was a frank talk which inevitably turned emotional.

Who would want their child traded for marriage just for survival? Who would want to see their daughter defiled?

Forced marriages are fuelling defilement cases in Mzimba, forcing district authorities to weigh in.

For two days at Jenda, five traditional authorities (T/As), Mzimba Heritage Association (Mziha), the district’s top police officer, a judicial officer and social welfare officer met to explore solutions to rampant sexual violence.

The district social welfare office in Mzimba South recorded nearly a 100 percent increase in child marriages within 10 months last year. The count almost doubled from 277 in 2019 to 528 by October 2020 when the survey was done.

Equally shocking, the southern half of the country’s largest district recorded 79 reported cases of defilement in 2019, but the figure rose to 101 from January to October 2020.

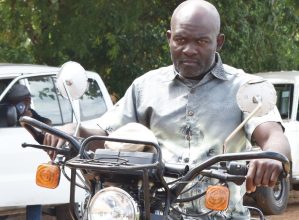

“If the data was collected across the vast district, the numbers could be in thousands,” says Patrick Mwale, executive director of Mzimba-based NGO, Communities in Development Activities (Coida).

The organisation works with communities to end violence against women and girls.

Coida convened duty-bearers to discuss ways to make gender-based violence history.

The gathering unanimously called for bold interventions to eliminate widespread early marriages and pregnancies.

Nearly half of Malawian girls marry before their 18th birthday and a third get pregnant during puberty.

District social welfare officer blame cultural pressure, saying some parents force girls to marry in exchange for various gifts as well as dowry.

“It happens. Some parents will marry off a girl child to receive cattle to be used as dowry for their sons,” Mwale explains, while facing the traditional leaders.

The chiefs disagree.

However, the community activist states: “In reality, a girl is abused for the sake of the boys’ welfare and other parents will simply allow a girl to get married for family survival.”

Concurring, police and social welfare officers say the cultural question keeps emerging in their community meetings.

But Chief Jalavikuba of Mzimba North says lobola (dowry) is part of the Ngoni culture, but does not fuel child marriages.

“It is just some selfish families that are using their children for gains and it would be wrong to blame it on culture,” says the youthful chief as elderly traditional authorities applaud him.

For Senior Chief Mtwalo, lobola “is just a token of appreciation, not payment for marrying someone”.

“Our culture does not support abuse of women and girls. Child marriages have nothing to do with culture or dowry,” argues the culture warrior.

The Ngonis of Mzimba have harmonised by-laws to protect girls from sexual abuse.

For the past years, activists and social welfare officers have been withdrawing girls from the outlawed marriages, but the young brides return to wedlock due to lack of support.

“What do you do if the girl you want to withdraw tells you she has no one else to look after her?” asks Mziha leader Moses Mkandawire.

And Mtwalo says by the time a girl is withdraw to go back to school, she might already be pregnant.

“If you talk about abortion, our society has a problem because colonial laws say no. How then do we help the situation?” he asks.

Mkandawire wants non-governmental organisations to constantly follow up and support girls withdrawn from marriage.

He argues: “Withdrawing girls from marriage must not be celebrated as an achievement or bait for more funding. Organisations must fully support the girls withdraws.

“NGOs in Malawi love to boast to donors that they have withdrawn thousands without caring what becomes of the withdrawn girls. The girls need counselling and, more importantly, economic empowerment.”

Coida is promoting economic empowerment of survivors of gender based violence.

So far, the organisation has recruited eight graduate interns who have trained 30 women and girls in modern farming methods, including production of organic fertiliser.

“From January, we will be providing beehives to some more women to empower them,” Mwale states.

He urges Malawians to act decisively against violence against women and girls and keep the conversation going.

In 2017, Parliament outlawed marriages involving boys and girls aged below 18.

“The law empowers chiefs to stop child marriages. Together, we can end child marriages. If the offence is criminal like defilement, we must report to police. We do not have the power to try criminal cases,” Senior Chief Mabilabo says.

In an interview, Senior Chief Mpherembe, secretary for Mzimba chiefs’ council, said the leaders will meet to take a common stand to safeguard women and girls.

“It is important for government and NGOs to work closely with traditional leaders because we have influence over our communities,” he says.

Coida has offered all chiefs registers to record acts of gender-based violence which often go unreported.

Recently, rising reports of sexual violence riled Minister of Homeland Security Richard Chimwendo-Banda who ordered citizens to punish offenders before handing them to police.

The minister later withdrew the statement, saying he made the remarks in anger after noticing the increase in defilement.