Treasury sleeps On tax treaties

Malawi’s tax treaties with the rest of the world are costing the country billions of kwacha in forgone revenue as some multinationals and private individuals take advantage of some archaic Double Tax Agreements (DTAs) to avoid tax.

Our analysis, corroborated with several tax specialists, shows that the country has several tax deals intact with other countries, but the pacts are mostly archaic and were signed by colonialists on behalf of Malawians.

In fact, we learnt that as Malawi slumbers, her neighbours such as Zambia and other developing countries, are currently at the height of reviewing their old tax treaties to reclaim their lost tax.

A tax treaty is an agreement between two countries to divide up and limit each country’s taxing rights. Among other things, tax treaties regulate when a country can or can’t tax foreign-owned companies.

Active vs inactive treaties

Our findings show that the country has five active tax treaties with South Africa, United Kingdom, France, Sweden and Switzerland.

We have also discovered that the country’s DTA with Netherlands was cancelled and renegotiated, but is not active now.

The country has similar agreements that were recently renegotiated with Malta, Zambia, Mauritius, Botswana, Morocco, Seychelles, Eswathini and Zimbabwe, but they are not active presently.

A source at Capital Hill, who is conversant with tax matters said in an interview that, so far, government has never estimated inconclusive and archaic revenue lost due to tax treaties.

“However, it has been noted that some treaties are not benefiting the country,” said the source who is also a tax specialist with over 20 years experience in tax policy and tax administration.

A 24-page UK/Malawi DTA that we have seen shows that it was signed on November 25 1955, but entered into force on April 24 1956.

The taxes which are subjected to the agreement include income tax (including surtax), the profits tax and the excess profits levy. On one hand, the taxes which are subjected to the same agreement in Malawi include income tax (super tax and undistributed tax (referred in the agreement as Malawi tax).

Among others, Article 3 of the agreement states that: “The industrial or commercial profits of a United Kingdom enterprise shall not be subject to Malawi tax unless the enterprise is engaged in trade business in Malawi through a permanent establishment situated therein.”

Similarly, Article nine of the agreement stipulates that an individual who is a resident of UK shall be exempt from Malawi tax on profits or remuneration in respect of personal (including professional) services performed within Malawi in any year of assessment if (a) he is present within Malawi for a period or periods not exceeding in the aggregate 183 days during that year and (b) the services are performed for or on behalf of a person resident in the UK and (c) the profits or remuneration are subject to UK tax.

This means that for over half a century, some British government enterprises as well as individuals have not been paying taxes following this pact.

Sir Gilbert Mc Call Rennie signed the tax deal on behalf of Malawians while R.A Butler signed on behalf of the UK government.

At that time, Malawi was part of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland and Rennie was British governor in the federation.

“The treaty simply implies that both governments should be benefiting from the tax deal, but Malawi is disadvantaged as it has no tangible or noticeable investments in the UK, which ironically has huge investments in the country including its expatriates,” said one Lilongwe-based economic governance expert working with an international firm.

Three main institutions are at centre stage of negotiating tax treaties on behalf of Malawians are Ministry of Finance, Malawi Revenue Authority (MRA) and the Ministry of Justice.

In an interview, Ministry of Justice spokesperson Pirirani Masanjala said it would be unfair to accuse the ministry of dragging the review of the tax treaties, stressing it only receives instructions from Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which he said is the policy holder and custodian of treaties.

But Gowokani Chijere- Chirwa, who teaches economics at Chancellor College—a constituent college of the University of Malawi said in an interview last week that when multinationals do not pay their fair share of tax, it implies that the very same local taxpayers are left to foot the bill; hence, burdening and pushing them into the abyss of poverty.

“It is high time Capital Hill cancelled all tax treaties more especially with tax haven countries and start afresh,” he suggested.

Counting economic gains, losses

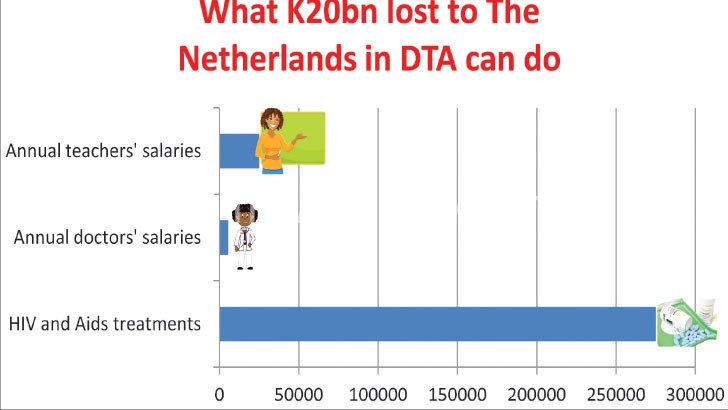

Due to her treaty with The Netherlands, in 2016 Malawi lost an estimated $27 million (about K20 billion) in lost taxes as the Australian mining company then Paladin shifted significant sums of money out of Malawi and back to Australia via The Netherlands, according to ActionAid Malawi report.

The report in 2016 revealed that if the $27 million was to be spent on public services for the people of Malawi instead, it could have paid for 275 000 annual HIV and Aids treatments, or 5 400 annual doctors’ salaries or as many as 25 000 annual teachers’ salaries.

“In several cases, tax treaties are helping money to flow untaxed from Malawi just like other developing countries to rich countries while making the world more unequal and exacerbating poverty,” said Yandura Chipeta, who is ActionAid programme specialist responsible for accountability and public services.

But tax expert Emanuel Kaluluma said a tax treaty is one of the first things any investor would want to know before deciding whether to invest in a particular country or not.

He said: “Therefore speaking against tax treaties would not be advisable. It is an important enzyme for foreign direct investment

“My view is that tax treaties are necessary, today with technological advancement people, especially investors, want free movement of capital and goods.”

On the other hand, however, Kaluluma said tax treaties are supposed to be reciprocal in their nature.

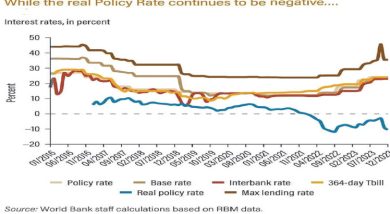

The country, however, continues to forgo tax revenue in the name of tax treaties at a time the country’s tax to gross domestic product (GDP) ratio remains low at 16 percent (using the rebased $10.9 billion or K8.1 trillion figure).

With such a ratio, the country is on the edge of the International Monetary Fund threshold as the Bretton Woods institution recommends a tax-to-GDP ratio of at least 15 percent to ensure that a country is able to invest in the future and achieve sustainable economic growth.

In an e-mail response, Ministry of Finance spokesperson Williams Banda said: “The major benefit of DTAs is that they help to prevent fiscal tax avoidance and evasion through profit shifting.

“They also help in the adoption of international tax reforms, diplomatic trade and economic ties while also providing assurances to investors on the prevention of double taxing.”

Borrowing leaf Dissatisfied with continued revenue losses emanating from tax treaties, many developing countries in the world are currently reviewing their DTAs with developed countries; hence, reclaiming their tax rights, said ActionAid’s Chipeta.

Recently, ActionAid c o m m i s s i o n e d a n independent research analysing more than 500 treaties that higher-income countries have with lower and lower middle income countries in Africa and Asia.

The research found that wealthier countries have the highest number of restrictive modern-era treaties that are severely limiting African and Asian countries’ taxing power.