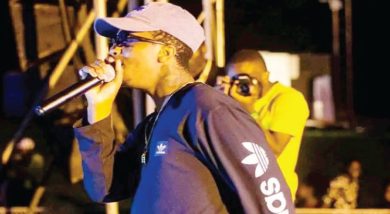

Ben mankhamba left everything for culture

The hit song Moyo wa M’tawuni meaning ‘town life’, was released some 20 years ago by musician Ben Michael Mankhamba. It addressed the challenges of living in urban areas and praised the laissez-faire of villagers.

The song resonated with, not strange in a country where the majority live below the poverty line and urban poverty is on an upward trajectory.

Fast forward a few years later, he was crowned chief of Chingalire Village on the ouskirts of Lilongwe City.

“When I was installed as a chief, I just accepted it and age-wise I was also mature enough to come to the village and take the position. But it was a tough decision to make,” Mankhamba told RFI’s Africa Calling.

Village homestay

Nestled inside a woodland, Chingalire Village is different from other villages, although urban development is a few kilometres away.

Mankhamba has transformed the village into a centre for cultural preservation.

The idea is to expose visitors, including international tourists, to typical Malawian village life and Mankhamba describes it as “a great place to share village life and where a real exchange of knowledge between guests and villagers takes place.”

The homestay also preserves history by passing on to the young folktales and traditional dances.

“It’s a model cultural village where tourists or people who just want to know about Malawian culture can come and learn a few things – maybe language, dressing, manners and food,” he says.

The centre has a women’s empowerment group, an under-five clinic, an amphitheaetre and a youth club where the young perform traditional dances.

In addition to performing at the centre, the dancers are hired to perform across the country.

Not only does this keep the young busy and prevent them from getting involved in harmful behaviour. They also earn money.

Dozens of young people told Africa Calling that they use the money to buy school supplies and supplement their family’s income.

Initially, some parents were not happy about their dedication to dancing, but have come around to it, he says.

“The other thing is that we have elders from different villages who are storytellers and we invite them to tell stories of old. It’s one way of also teaching and passing on history to the youth,” he added.

Cultural and environmental

The chief is also passionate about the environment and actively protects the woodland and the animals found at the centre.

As well as encouraging his ‘subjects’ to plant trees, he also trains women to make stoves that use less wood.

The establishment has 10 permanent workers and employs dozens more on part-time basis when there is a performance.

Mankhamba said the people in the village are reaping the benefits of the centre from learning to plant trees in their households, to keeping the traditions alive.

The initiative is commendable as youth are exposed to the traditional values, according to Mwayi Lusaka, a lecturer in history and heritage studies at Mzuzu University.

He notes that the dances performed at the cultural village are not specific to Malawian ethnic groups, but also comes from countries where these groups originated.

“In every culture there is a context and medium in which they express their identity, in which they communicate their cultural values,” says Lusaka.

“For example, the cultural values to do with initiation, teaching right conduct and behaviour among the youth who are graduating to adulthood and these dances are the medium through which these cultural values are transmitted. Apart from being a vehicle, they are also a signifier of identity and belonging,” he adds.

Metamorphosis of chief and village

Mankhamba’s new role entailed a change of his funky look, including cutting off his trademark dreadlocks.

“The elders thought it was not good for the community and I was forced to chop them off. It was really bad because it was like I lost my identity,” he says, adding that no one recognised him on the street.

“People thought I had stopped performing music which made me lose gigs. Yet, I was still doing music and it is just that maybe my looks changed,” says Mankhamba.

Today, although Mankhamba’s songs don’t receive massive airplay, the older generation still holds on to them dearly. He still performs for corporate functions and transfers the proceeds to his foundation.

But how does someone who was accustomed to the limelight and the bustle of urban life feel comfortable with country life?

“It was tough at first, but when I started doing what am doing in the village, working with the youth and doing cultural works, my passion for the project helped,” he says.

“I’m now proud and I don’t regret that I left the town and came here to the village.”

This story was originally presented on RFI’s Africa Calling podcast and it has been reproduced with permission from the author.