Beyond the art

Twenty-nine-year-old Anderson Alfred Chipwaila, popularly known as Mesho, is now behind bars.

In one hunt for glory, he used art not to comment on or cement the social fabric that holds society. He used it to mock and attack that fabric which is tolerance.

Before him, Mwiza Chavura, courted criticism when, in another apparent target at fame, he celebrated a crime.

Perhaps because his niche is urban, usually semi-liberal, and did not attack the ideals that have held together the peace of this country, an apology was all Chavura made.

Still, his career appears to have stalled or failed to start off after that embarrassment.

Lest people forget, there was also Born Chriss, real name James Kamthumba. The 26-year-old up-and-coming artist who, in the early days of his career staggered towards the loathed and dreadful.

Born Chriss pelted stones of indecency at a femcee with a better value and a fame than him, Kwin Bee (Bertha Lomoti).

He was dragged to court and given punishment to do 480 hours of community service at Ndirande Health Centre in Blantyre which, even if considered lenient, is not a thing to celebrate.

It is now becoming a trend, and a fashion it seems, to offend others to prop up one’s fame.

It appears that some musicians have failed to realise the responsibility that their art must carry but are quick to realise the shortcut to fame: controversy.

In the days of a liberalised production and a weak as well as ineffective censorship, artists appear to think that the only responsibility that their art has is to them. That if their art helps them to be at the top of the ladder then the opinion or beliefs of others do not matter.

The aspect of using art to express grievances is not such a new phenomenon in the Malawian context.

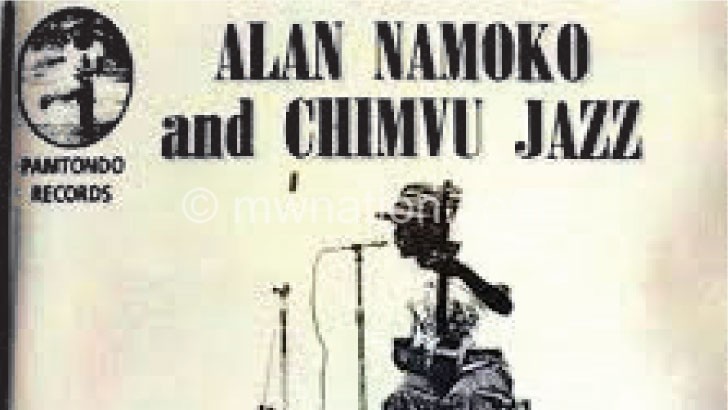

Allan Namoko, the guitarist and vocalist who has an inerasable space in the history of local music, mostly built his career around airing grievances.

Those who know the life he lived tell that his characters and stories were mostly non-fictional

His family disapproves of his choice of marriage, it was to music he went. However, instead of castigating them—as most musicians prefer to express their anger and frustrations today—he asks that there should be reconciliation. He calls for third parties to bring peace.

Micheal Yekha, another great in the music industry, most likely bothered by what people spoke of him used art to address the people.

He, however, did not go about calling them names or trading expletives that would cringe the conservative society Malawi has largely been. He glorified himself.

It is not only in the past that cases have appeared in which music has been used to air grievances or frustrations. In recent days, there have been musicians who have understood that music, apart from being a vehicle that can carry anger, is also a matchstick that can set the anger ablaze.

Tay Grin, now wanting a shot at politics, has as well used his music to respond to all criticism he gets as an artist.

He neither mentions names, nor castigates. He simply mentions the criticism and labels the people behind the noise as noise-makers.

His brother in politics, Dan Lu, does the same. In Akumva pain, Dan Lu is addressing critics—or what are fashionably called haters in the urban music circles and modern lingua. He does it with decency. Only a court of public opinion can convict him of hate speech for the song.

It might be the fame that the others already had before airing out their grievances. That, maybe, they did not need to go to extremes to communicate.

Maybe they even understood the power of music.

It seems lately, however, most musicians—and they are usually young—do not understand that beyond the art lies responsibility. That music, even if personal, is not personal. It is public with far-reaching consequences on society.

No wonder Musicians Union of Malawi (MUM) president, the Reverend Chimwemwe Mhango, stated that Mesho’s judgement should be a wakeup call to all artists that, despite being in the creative industry, they are bonafide Malawians who are not above the law and have an obligation to promote unity and peace.