How Chakwera Boxed in Mlusu

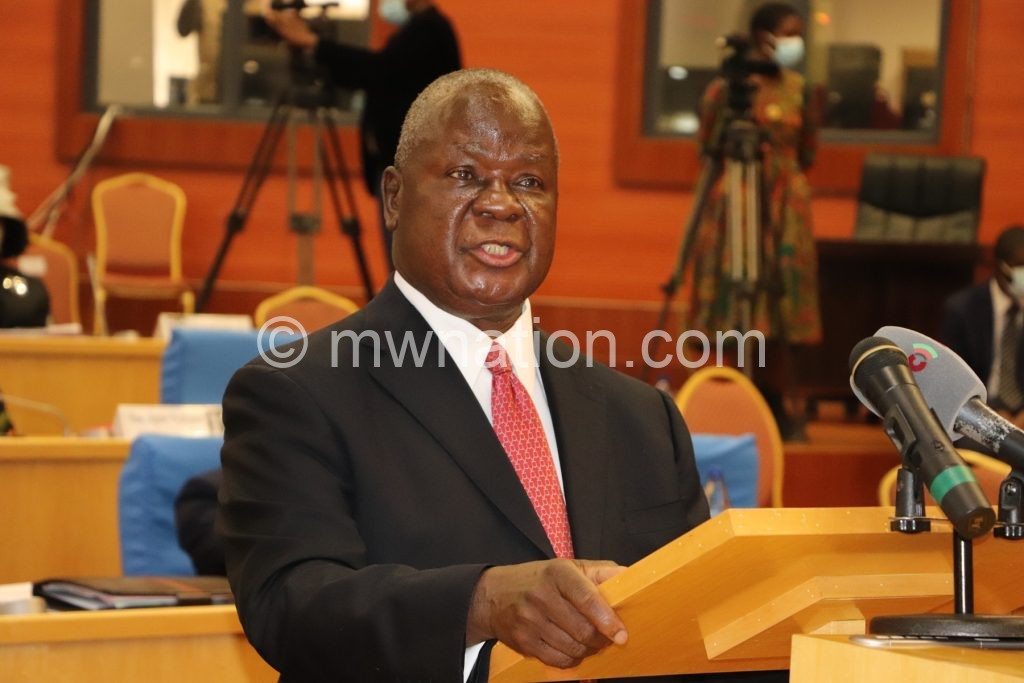

Finance Minister Felix Mlusu’s work is cut out for him by his boss, President Lazarus Chakwera.

As he walks up Parliament Building in Lilongwe to present the next budget today, Mlusu must have a fiscal plan that is clear on how it will provide three meals a day to every Malawian household; outline a strategy for creating wealth and set forth a plan for giving jobs to millions of Malawians searching for employment.

That is what Chakwera—in his State Opening Address of the third Meeting in the 49th Session of Parliament on May 12 this year—said he wants to achieve by 2025.

That presidential commitment boxes in Mlusu into a position where he must swim or sink on the three agenda items that must come true through the budget amid disappearing fiscal space and an economy in doldrums.

The President’s likely expansive and expensive agenda—which was not accompanied by a revenue generation plan—is set to exert fiscal pressure on the 2021/22 National Budget; potentially lead to mounting public debt and undercut efforts at fiscal sustainability.

Yet, his political capital can rise or fall on the three promises he has made to Malawians as he plots a possible 2025 presidential run for a second term.

“Firstly, we aim to achieve permanent food security for all Malawians so that hunger is forever a thing of the past. Secondly, we aim to create jobs for Malawi’s youth so that they are self-reliant, active, and productive contributors to Malawi’s development. Thirdly, we aim to create wealth for Malawians so that they are the primary beneficiaries of any economic activity we foster,” said the President.

Chakwera said his administration would invest in what he dubbed accelerators—infrastructure, human capital and digitisation—to achieve his agenda and propel Malawi into an upper middle income nation by the year 2030 when individual income is expected to rise to at least $1 036 per year from the current $600.

The President said his infrastructure accelerator will focus on transport and energy; his human capital development plan will prioritise health and education while the third trigger involves governance reform and digitisation.

Chakwera’s three-pronged agenda means that Mlusu will have to align budget priorities to the President’s wish list—not the easiest of tasks in a country with serious deficiencies in every sector.

Mlusu will have to delicately balance competing priorities amid a thinning resource envelope and increasing statutory expenditures crowding out capital investments and starving social sectors of much needed spending that largely benefits the poor.

Already, government’s fiscal space is dwindling on the back of a rising public debt stock to feed a historic budget deficit, which in the current fiscal year has risen to 8.8 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) from 4.6 percent three years ago.

Primary budget deficit, as of February 2021, was also revised upwards to a record K810 billion from K755 billion during the initial design of the 2020/21 budget.

The approved budget was initially pegged at K2.2 trillion, but was later revised at mid-year to K2.3 trillion on the back of increased expenditure needs by government amid shrinking revenue base. This figure is likely to jump as the Tonse administration feels compelled to deliver on his campaign promises that cannot match the fiscal realities confronting the administration.

Since 2011, Malawi’s public debt as a ratio of GDP has more than doubled to at least 60 percent, which takes huge resources from the budget to service debts.

Large welfare programmes such as the Affordable Inputs Programme whose budget has quadrupled in the current fiscal year are some of the major factors pushing up the deficit while contributing insignificantly to national agricultural output and overall economic growth.

Corruption, fraud, unrealistic public sector wage demands and outright wasteful spending on non-essential activities such as travel are also significant drivers of high deficits and public debts—all bordering on governance that the President said he would invest in and is Mlusu’s responsibility to deliver, particularly in the area of public finance management.

Furthermore, shrinking tax revenue amid weak private sector performance and a fast growing consumption-centric spending that has left little money for the capital formation necessary to anchor broad-based economic growth, makes Mlusu’s job even tougher.

The President’s agenda also faces climate change risk as crop production—the nexus of the country’s food security strategy—heavily relies on rain-fed agriculture easily hit by droughts or flash floods as forest cover disappears into charcoal and firewood.

Unreliable energy supply, the lagging effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, which has depressed economic activities due to travel restrictions and social distancing measures, pose further challenges to the 2021/22 budget, which ends on March 31 as government has reverted the fiscal calendar to April-March financial year from 2022.

With the economy suffering from protracted high unemployment and weak output due to the stunting effects of Covid-19 and traditional structural bottlenecks bedevilling the Malawi economy, Mlusu has little room to manoeuvre fiscal policy—and that includes taxation.

The twin problems of large deficits and economic stagnation will require some miraculous balancing act if Mlusu has any hope of delivering the President’s lofty agenda and lift Malawians out of poverty, whose rate has been stuck at 50 percent for at least a decade.