Phwezi Girls’ K2m regret

A breakdown in a biogas plant at Phwezi Girls Secondary School has exposed huge savings learning institutions can make by churning out cooking energy from student’s faeces and food waste.

Head teacher Zondiwe Nkhata fondly remembers the gas-making plant that would be saving almost K1.95 million a term if it were still functioning.

Most boarding schools in the country burn truckloads of logs for cooking, wiping out vanishing forests and exposing cooks to toxic fumes that kill someone every eight seconds globally. According to the 2018 Energy Report, indoor air pollution kills about seven million people a year in a world where 3 billion people—40 percent of the world’s population—who still use charcoal, firewood, coal and kerosene for cooking despite the agenda for clean, affordable sustainable energy for all.

As early as 1997, Phwezi Girls stopped using firewood after installing a system which turns human excreta and food leftovers into gas for cooking meals for almost 800 learners.

Nkhata still recalls the savings a decade after a breakdown in the biogas system forced the Northern Region’s oldest private school to revert to burning logs, which it buys from the Department of Forestry.

In an interview, he revealed the learning institution shells just about K1.95 million on enough firewood to fill 10 articulated trucks carrying 30 tonnes each. This means the one-time smokeless kitchen would be saving about K6 million per academic year using biogas.

Nkhata put the smoky expenditure in context: “The budget for firewood is huge. A 30-tonne truck makes 10 trips to Rumphi Forestry Office, where we buy the firewood patrol squads confiscate from people who cut trees illegally.

“Had the biogas plant been in use, we would have been putting this sum to other pressing needs while saving a lot of indigenous trees which take a lot of years to mature.”

With up to three percent of trees vanishing every year, the country is losing trees at the fastest rate in southern Africa and the sixth globally.

Loss and damage

The damage is visible in Phwezi and surrounding areas where tobacco estates are sprawling on hilltops and hillsides. Emerging crop fields have left gullied, bare stretches where lush tropical forests stood.

As trees crash to the ground to pave the way for new tobacco fields, many more are felled by farmers lacking sustainable sources of fuel for processing the country’s largest export for the world market.

An aerial photograph of the northern hills, where farmers dry the leaf crop in sheds and cross-polls made of trees, graces the Tobacco Atlas. The report by the American Cancer Society and Vital Strategies in Cape Town in April tracks public health and environmental impacts of the export crop from the nursery bed to cigarette burning to ash.

The massive loss of trees in Phwezi and Bale hills has left South Rukuru River murky with soils from the eroded stunning slopes.

This year, flush floods swept away crops and shops in Mzokoto and surrounding areas, hauling away rusty steel culverts at Phwezi Trading Centre and Bale. This left travellers on the M1 stranded for days.

When he visited 75 households affected by flush floods, Minister of Transport and Infrastructural Development Jappi Mhango blamed the disaster on human activity.

“It’s sad that a lot of property has been lost. People should not build houses close to rivers and communities uphill should also avoid carelessly cutting down of trees. Some of these disasters can be avoided,” he said when he visited 75 households hit by the floods.

According to the Department of Forestry, 98 percent of the country’s population cooks using firewood and charcoal. This exerts pressure on forests.

The National Renewable Energy Strategy (2017 to 2022) names biogas among appropriate alternatives to firewood and charcoal.

Ensuring that every boarding school, prison, hospital and lodge population uses biogas would save money, slow down the loss of the green cover and prevent disasters resulting from environmental degradation, says Environmental Affairs Department spokesperson Sangwani Phiri.

“Institutions with centralised populations have a reliable source of stools. The bigger the population, the more the stools and gas they can produce. This would help save a lot of land being degraded as trees disappear. Burning ten 30-tonne trucks of logs every three months is too many trees going up in smoke, he says.

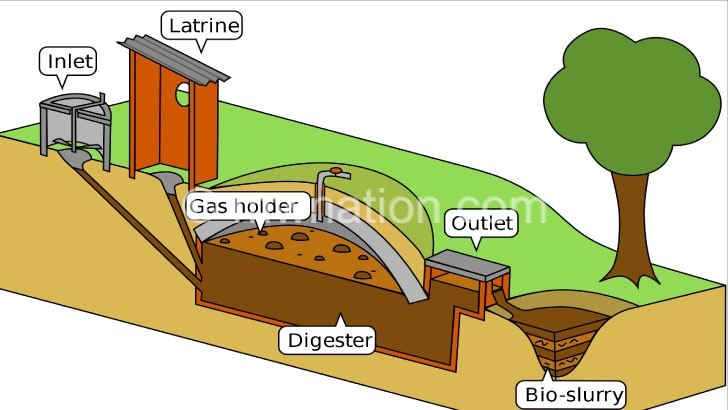

Here is how it works: From the communal toilets, the stools are channelled into an underground tank or digester where they settle down, separating solid waste from water. With time, the solids sink to the bottom while gas from fermenting sludge goes into a 100-meter pipeline to the kitchen.

Poo power?

Some people fear that turning human excreta and food leftover into gas for cooking contaminates food and air.

But Phwezi Girls former students says it emits no foul smell or germs to worry about.

“I didn’t have any problem. The cooking was quick and the food was well prepared. The kitchen was smokeless and tidy. The toilets and surroundings were hygienic because the biogas partly reduces waste,” says former kitchen prefect Muhlabase Mughogho. n