‘Soaring debt cost to economy’

In 10 years from 2007 to 2017, Malawi has spent K123 billion on debt service-cash that is required to cover the repayment of interest and principal on a debt for the period, out of which K52 billion was interest payments, a situation analysts say may choke the economy at one point.

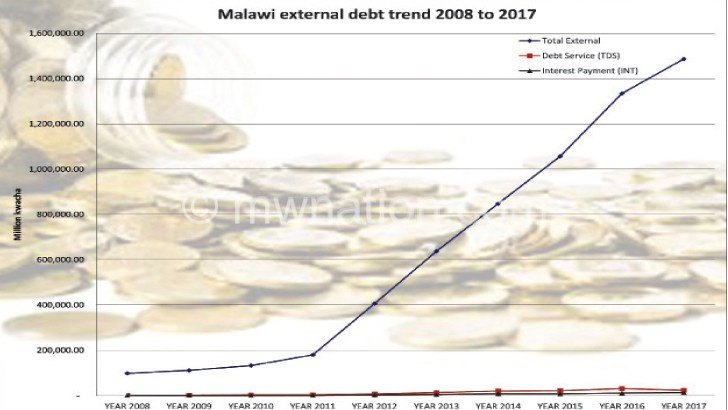

Published figures from the Reserve Bank of Malawi (RBM) indicates that the country’s external debt has soared from K98 billion in 2008 with a debt service of K1.8 billion, to K1.5 trillion in 2017, with a debt service of K13 billion.

This has pushed up the country’s debt-to-gross domestic product (GDP), which has been rising rapidly during the last decade standing at about 55 percent of GDP, compared to less than 30 percent 10 years ago, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Figures from Treasury show that prior to 2006, the country’s external debt stock was about $3 billion, an equivalent of 150 percent of GDP.

Prior to Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (Hipc), the external debt level was slashed from 90 percent of GDP to 8 percent in (actual) present value.

The debt stock fell drastically to just under $500 million, representing an 11 percent drop, thanks to Hipc initiative and the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI).

The soaring external debt in the 10 years to 2017 means that the country has spent money it could have spent on roads maintenance (K16 billion), health sector (KK37 billion), education sector (K25 billion), agriculture sector (K4 billion), elections (K11 billion) and maize purchases (K35 billion), if we are to go by the 2017/18 approved statement.

In a written response to a questionnaire on Tuesday, IMF resident representative Jack Ree said while it is true that Malawi’s debt to GDP ratio has been rising rapidly during the last decade or so, getting out of the debt would require that the country stay the course of macroeconomic stabilisation.

“Just like families and businesses, countries cannot allow its debt to rise indefinitely. At one point, you will find yourself broke. That said, debt is not always a bad thing, especially when the money is borrowed in reasonably good terms and used for investment which is productive or used to pay for itself.

“Can we get out of the debt trap? A short answer would be yes. But that would require that we stay the course of macroeconomic stabilisation. On top of that, we also need to make sure that large infrastructure projects are selected carefully and wisely, so that the projects will rise to the promises of economic returns while minimising negative impacts on debt dynamics,” he said.

In a separate interview, Economics Association of Malawi (Ecama) executive director Maleka Thula said the rising debt levels raises concerns on debt sustainability.

“It is important to note that as a country we have, on average, consistently remained within acceptable borrowing thresholds or limits of 20 percent and 30 percent of GDP for domestic and foreign debt, respectively. However, the country’s debt stock has steadily risen since Hipc debt cancelation in 2008, thus raising concerns of debt sustainability.

“If such borrowing is meant to finance development or productive sectors of the economy other than consumption as is usually feared then issues of debt trap or sustainability are of no concern. This is because anticipated gains or proceeds from such investments would be used to repay such loans,” he said.