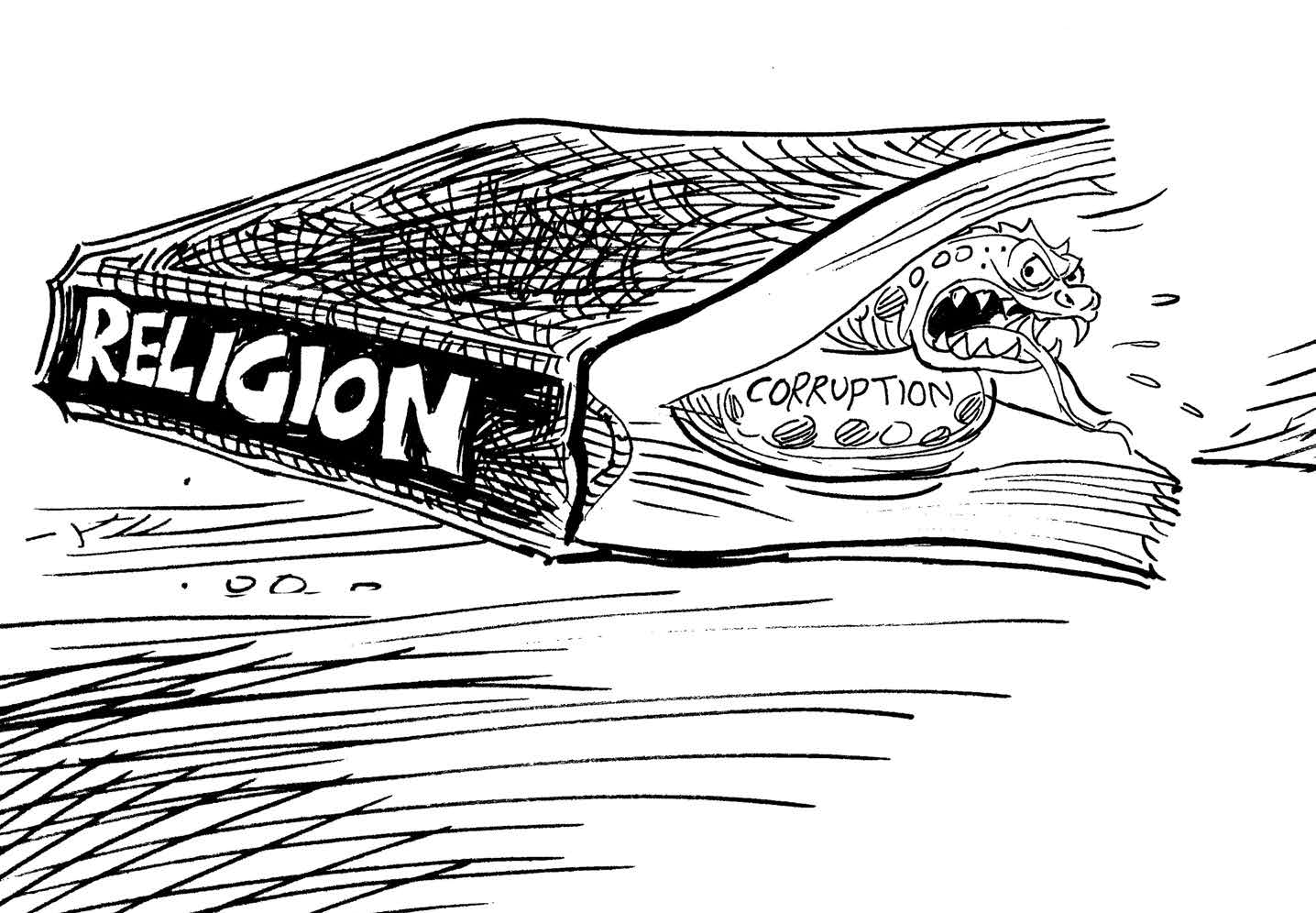

Whose fight is the corruption fight?

Recently I read about some civil society activists asking for the resignation of the Anti-Corruption Bureau (ACB) director general allegedly for incompetence and lacking strategy to fight corruption. The grounds for incompetence and lack of strategy included claims about loss of important case documents and accusations on the bureau’s penchant for making too many arrests with little to show in terms of court appearances.

This story nudged me into thinking about many questions on the corruption fight in Malawi and particularly, whose fight is the corruption fight? Could it be that the ACB is perceived to be the night guard that must watch over our valuable life and property while we slumber? How safe is the wellbeing of our country when we all sit back as spectators waiting for the final whistle to hear the results?

I must hasten to admit that there is indeed a widely held perception that the fight against corruption belongs to the ACB and that if the country will win the fight the bureau must have all the armoury and latitude to wage the war effectively. Further, some quarters feel that winning the war on corruption will be measured by the number of convictions that the ACB secures in court while others find comfort in the character and performance of an incumbent head of the institution.

This unfortunately is a very short-sighted view to a very complex social phenomenon that cannot end at the door-step of the institution neither by mere arrests and sending people to serve prison sentences.

The Malawi National Anti-Corruption Strategy II (NACS II), just as its predecessor strategy, recognises the complex nature of corruption and hence seeks a holistic approach of ensuring that corruption is tackled from different dimensions by all sectors of the society. On one hand the NACS II envisages a multi-sectoral approach as being effective on the basis that corruption is a symptom of a broken social order whose fixing requires rebuilding all dimensions of society. On the other hand, the strategy recognises the importance of the role that every sector of society can play to effectively deal with corruption.

In simple terms, based on a model developed by Transparency International, the national anti-corruption strategy assumes that the war on corruption should focus on building a strong national integrity system whereupon all sectors are bound by a set of values that determine personal and institutional character and conduct. For Malawi, the integrity system is held together by 12 pillars which are the Executive, the Legislature, the Judiciary, the private sector, academia, civil society, faith-based organisations, women, the youth, local government, traditional leaders and the media. Each of these pillars is tasked with roles to play towards promoting a culture of integrity in the respective sector which in the end will contribute to corruption prevention. In a way, the national anti-corruption strategy emphasizes on prevention as the most effective means of fighting corruption.

Beyond the pillars stated above, a strong national integrity system must sit on a strong foundation with supportive political institutions, healthy relationships among different social groups, economic stability and strong cultural foundations built on norms and values consistent with integrity.

In this set-up of an anti-corruption strategy, the ACB is merely anchoring a policy whose success depends on the performance of all the pillars mentioned above and how social, political and economic foundations support the system for building a society of integrity.

Therefore, while it is important that the ACB performs its mandate as provided by the law, it is equally important to manage our expectations in terms of what role the ACB can play to stop people from engaging in corrupt practices. An effective anti-corruption strategy can only be realised when all sectors of society are empowered and in full support of cultivating a culture of integrity in every social, cultural and economic endeavour. The state must support programs that aim to build a system that not only punishes corruption offenders but nurtures the growth of a citizenry that abhors corruption not for fear of arrests or conviction but because they see value in doing the right thing.

Corruption in Malawi and anywhere in the world is too big and too complex to be left to the wisdom and capabilities of one person or one institution. Everyone has a stake in the war on corruption and must rise to the occasion. As much as possible we should resist the temptation to be mere spectators or commentators who only speak out when it is economically or politically convenient to do so. The war on corruption belongs to everyone.