Debt fund Stirs panic

Economists have faulted Malawi Government plans to establish a Debt Retirement Fund effective July 1, arguing that the timing is wrong and that Malawi has not demonstrated capacity to retire its high public debt stock.

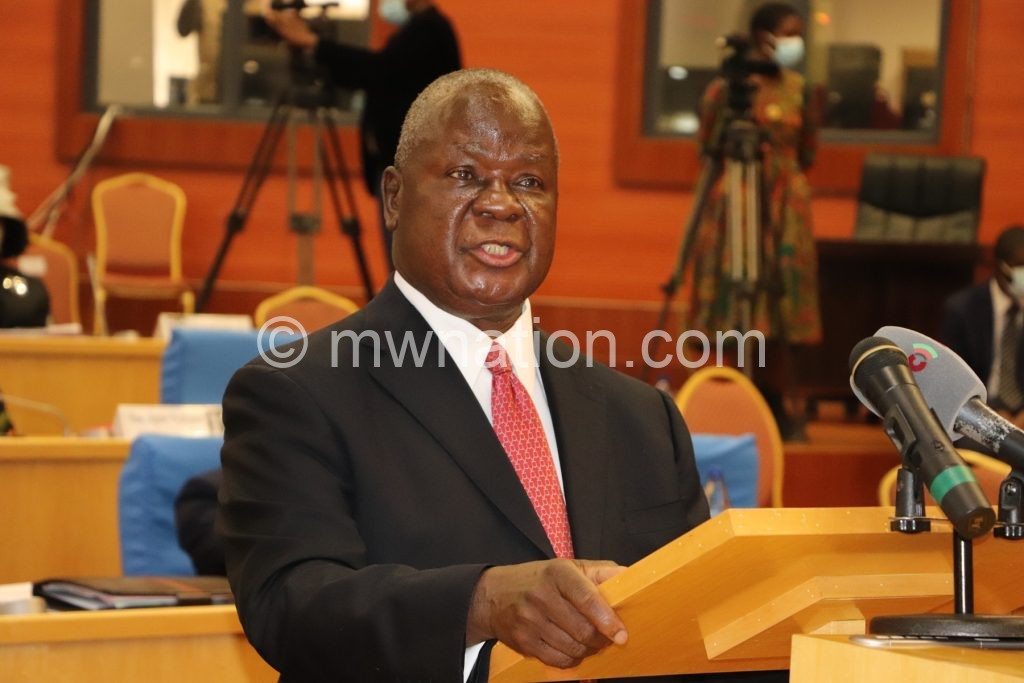

The reactions follow an announcement by Minister of Finance Felix Mlusu in his maiden national budget tabled in Parliament on September 11 2020.

He said the recent accumulation of total public debt (TPD) stock, which has now climbed to K4.8 trillion or 54 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) as at December 31 2020, justified the establishment of the fund.

In the Mid-Year Budget Review Statement tabled on February 26, the minister told Parliament that the Ministry of Finance has completed the identification and quantification of the possible sources of finance for the fund, adding that the implementation of the fund is expected to be approved by Cabinet in time for its roll out on July 1 this year.

Sources have confided in The Nation that one possible source of financing the fund is the introduction of a levy on some products with inelastic demand for a defined period.

But reacting to the plan in a written response, Zimbabwe-based economist Tirivangani Mutazu, who is also senior policy analyst for African Forum and Network on Debt and Development, said while government is obliged to repay its debt, introducing any tax obligation for its citizens to retire the debt is insensitive and ill-advised.

He said: “Majority of African countries, Malawi included, are yet to recover from Covid-19-induced economic and health impacts. Citizens have lost their jobs and sources of income.

“Introducing any tax obligations in whatever form is insensitive. The government needs to tame its borrowing appetite and account for the built-up debts on its books.”

Mutazu said the challenge with such funds revolve around transparency, corruption, accountability and wrong investment decisions.

On the long-term plans of turning a Debt Retirement Fund into a Sovereign Wealth Fund, the economist said such sovereign funds are commonly established to harness savings from mineral rents such as oil, uranium, diamonds and gold.

Mutazu said: “The African region has many country cases with badly managed Sovereign Wealth Funds. The Angolan Fund is an example riddled with corruption.

“The good cases normally cited include Botswana and South Africa. Internationally the Norwegian Fund is cited as best practice.”

In his comments, economist

Noel Lihiku, who is based at Southern Africa Development Community headquarters in Gaborone, Botswana, but speaking in his personal capacity, said introducing a levy will tilt the tax burden to the consumers most of whom are the poor.

He said the burden of this levy will be borne by the ordinary Malawians since products that have inelastic demand are the basics.

Said Lihiku: “This is not the right time to choke the citizens with more levies. It may counter all the economic recovery programmes being pursued to move out of the recession that has come as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic.

“However, if the category of the products to be targeted falls in the category of cigarettes, alcoholic beverages then this will work in the long-term.”

Tax experts have for long argued that in Malawi, the tax burden is heavy on consumers and requires serious overhaul.

While describing the intention to establish the fund as plausible, economist Milward Tobias, who is also executive director for Centre for Consultancy and Research, said the key concern is that government has not demonstrated capacity to retire debt, adding that the best way is first to minimise and at best stop new borrowing.

He said: “I argued in my reaction to first 100 days of Tonse Alliance administration and I said the indications, so far, seem to show that this administration is weak on economic management. I still stand by that.

“No one can take seriously a leadership that

is fond of introducing conflicting policies and pushing the burden to citizens. Introducing levy means digging deep into people’s pockets.”

Despite so many taxes and levies, Tobias said that public services are still inadequate and of poor quality.

During the Economics Association of Malawi Annual Lake shore Conference last November, Vice-President Saulos Chilima, who is also Minister of Economic Planning and

Development; and Public Sector Reforms, also touched on the establishment of the fund.

But he said that it will require government to introduce such a levy on goods with inelastic demand.

Said Chilima: “Proceeds from the levy will be ring-fenced and entirely used to retire public debt until debt levels subside to within sustainable levels.”

Demand is price inelastic when a change in price causes a smaller or no percentage change in demand. Examples of goods with inelastic demand include fuel, cigarettes, salt, water and electricity.

M i n i s t r y of Fi n a n c e spokesperson Williams Banda was yet to respond to our questionnaire to react to the concerns raised by economic experts on the plans to establish the fund.

At K4.8 trillion, the nominal value of the country’s debt stock is double the size of the country’s 2020/21 revised national budget pegged at K2.3 trillion.

A break-down of the TPD stock figure shows that as at end-December 2020, external or foreign debt was K2.04 trillion or 23 percent of GDP, while domestic debt was K2.72 trillion or 31 percent of GDP.

According to the 2020/21 Mid- Year Public Debt Report, on the fiscal front, between June and December last year, government had to contend with a number of challenges which have a bearing on public debt, including the high and rising primary deficit financed by domestic debt contracted at high interest rates.

In the budget, Mlusu increased further the budget deficit from K755 billion to K810.7 billion amid a squeezed fiscal space characterised by little revenue generation. The deficit alone is 10 percent of the nominal GDP and is the worst ever gap between revenues and expenditure in the history of the country in nominal terms.

Treasury plans to finance the K810.7 billion yawning budget deficit through foreign financing of K246.3 billion, with the balance of K564.4 billion programmed to be financed through domestic borrowing.

The high primary deficit is largely on account of underperformance in revenues, Covid-19-related expenditures, the expenditures on the Affordable Inputs Programme, statutory expenditures, including the public wage bill.