Education in multiparty Malawi

If you can read this, thank a teacher. No one can become an engineer, lawyer, statistician or medical doctor without some education, not just schooling.

The importance of a more effective, responsive and results-oriented education system for all needs no overemphasis.

In Malawi, the introduction of free primary education in 1994 marked a fundamental policy shift in the basic education sector since the restoration of the multiparty era 25 years ago.

Enrolment surged by 51 percent from 1.89 million in the 1993 academic year to 2.86 million in 1994–and it continues to soar.

Last year, there were 5.07 million learners–comprising 2.51 million boys and 2.55 million girls.

According to officials figures below, enrolment of early childhood development (ECD) centres has increased by 1 194 percent from 1996 to 2009.

Despite free primary education and mushrooming of community-based childcare centres (CBCCs), government statistics in 2012 revealed shocking primary school drop-out rates.

In the 2011/12 academic year, primary schools registered a national survival rate of 53 percent in the final grade. In secondary school, 38 percent survived last year.

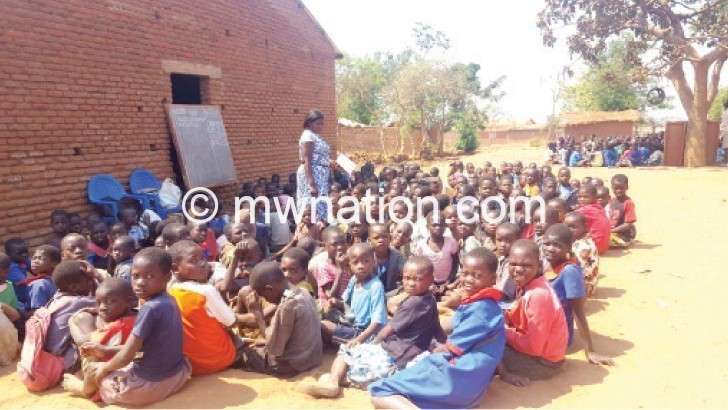

The education sector continues to be haunted with shortages. A single permanent classroom sits 121 pupils while a qualified teacher serves about 77 learners.

The multiparty era has also heralded key successes.

Net enrolment has exponentially increased at all levels from pre-school to universities partly due to increased involvement of the private sector.

Government has also enacted well-decorated legal and policy framework, including the National Education Policy (NEP), National Education Strategic Plan (Nesp), National Inclusive Education Strategy, the Education Act (2013).

Despite economic challenges, government allocates more finances to education.

However, the funds are not adequate to address the myriad challenges slowing the sector.

The greatest challenge is gross internal inefficiency, especially high dropout and repetition rates as well as low transition and completion rates.

For example, the transition rates to secondary and tertiary education is at 41 percent and 32 percent, respectively.

Rural schools are poorly resourced and unable to provide quality education to the majority of the population.

These inequities are clear even during selection to public universities.

During the 2017/18 university selection, only 14 percent of the selected students came from community day secondary schools (CDSS). Government-subvented secondary schools produced 53 percent while private schools had 33 percent.

This unjustifiable rural-urban divide traps the rural masses in poverty. There is need for affirmative action to address such inequalities.

Government is implementing the highly criticised equitable system of selecting learners to public universities.

CDSSs could have their quota for admission into the public universities coupled with provision of bridging courses to such students.

Malawi has low literacy levels. According to World Bank, about 62 percent of Malawians aged 15 and above can read and write.

Poor infrastructure, low survival rate and overcrowded classes are everyday realities of the democratic Malawi.

These harsh realities demonstrate that embellished policies and laws do not improve education outcomes without political will to show anticipated results on the ground.

The country must unequivocally shift from sheer political rhetoric to commitment and accountability. We must implement international protocols, treaties and national policies that we commit to.

Fulfil the Education 2030 promises on educational financing.

While education enjoys 17 percent of the 2018/19 National Budget being debated in Parliament, the development budget investment remains low and shortage of infrastructure will continue.

This shows that the nation has not learnt anything from a substandard classroom which killed four pupils and injured 53 at Nantchengwa Primary School in Zomba.

In the current budget, government must identify money for construction of school blocks and renovation of substandard structures. Treasury can save over K15 billion for building classrooms by cutting highly abused allocations for Farm Input Subsidy Programme, Decent Housing Subsidy and tree-planting initiative and maize procurement.

There is need to have a responsive government and parliament that would rise beyond politics.