World bank tips Malawi on growth

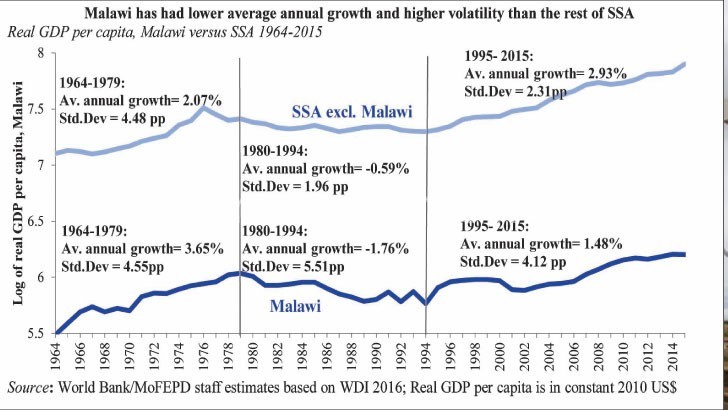

Despite decades of development efforts and significant foreign aid, Malawi’s weak and volatile economic growth performance has persisted mainly due to governance, institutions and policies over the long run, the World Bank has said.

In its December 2018 Systematic Country Diagnostic: Breaking the Cycle of Low Growth and Slow Poverty Reduction, the bank says with weak institutions and limited policy buffers, however, the adverse consequences of negative shocks tend to cumulate, so low growth becomes entrenched.

According to the bank, weak governance and institutions contribute to Malawi’s poor development performance.

“Malawi’s stagnation is in large part driven by a stable but low-level equilibrium, in which a small group of elites compete for power and political survival through rent seeking. The competitive-clientelist political settlement creates strong incentives for policies that can be seen to address short-term popular needs while undermining the ability to credibly commit to fiscal discipline and long-term reforms needed to spur productive structural transformation.

“Macroeconomic instability, recurrent natural shocks, and limited transformation have made it difficult to achieve meaningful reductions in poverty. Malawi’s pace of poverty reduction has been slower than the SSA average and slower than the decline in neighbouring countries, which had higher poverty rates than Malawi in the early 2000s, but recorded significantly lower rates by 2013.”

According to the bank, potential pathways for Malawi to break its cycle of low growth and slow poverty reduction include increasing agricultural productivity, diversifying the economy and creating jobs, harnessing the demographic dividend and building human capital as well as building resilience against shocks.

“Several aspects of weak fiscal management in Malawi deserve attention. These include: weak medium-term budget planning, budgetary indiscipline and weak expenditure control, pre-election budget overruns and slow fiscal response to shocks. “

Treasury revised downwards the 2018/19 fiscal overall deficit, including grants, from 4.5 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP) to 3.8 percent of GDP, a move analysts argued was insignificant to trigger intended results.

Earlier, government had planned to end the 2018/19 financial year with a fiscal deficit of K242.9 billion. As compared to the previous financial year, there was a seven percent increase, with government projecting the 2017/18 financial year to end with an estimated K224.5 billion deficit.

Finance and corporate governance strategy professor at The Polytechnic, James Kamwachale Khomba, earlier observed that every government, including those of developed nations, have deficits, but if used correctly, it can be a catalyst for development.