Financial inclusion, an opportunity for Africa

Mobile money has become an important enabler of financial inclusion in Sub-Saharan Africa—especially for women—as a driver of account ownership and account usage through mobile payments, saving, and borrowing.

Mobile money accounts both grew and spread across Africa from 2014 to 2021, according to Tralac survey.

There are no universally agreed definitions of digital economy, digital trade and e-commerce. These terms, though distinct, are often used inter-changeably on the same issues.

Digital economy is understood as that part of economic output derived primarily from digital technologies with a business model based on digital goods and services. The main components of the digital economy include fundamental innovations (semiconductors, processors), core technologies (computers, electronic devices) and enabling infrastructures (the Internet and telecoms networks), digital and information technology such as digital platforms, mobile applications and payment services.

The digital economy encompasses online platforms such as Google, Facebook and Amazon, platform-enabled services such as Uber and Airbnb, trade in electronic transmissions like online delivery of software, music, e-books, films and video game and mobile technology and applications including mobile payment services.

Fintech

Fintech (financial technology) it is generally used to describe businesses using technology for financial services. This can mean new financial services such as mobile money, but typically means new ways of delivering existing financial services.

The technology might provide a new or better user interface such as an app, it might enable a greater reach (more people have mobile phones than local bank branches) or lower costs for example ‘robo-advisors’ use algorithms rather than humans to give investment advice, typically making the advice cheaper.

Fintech solutions are facilitating international trade in several ways by increasing access to finance, especially for micro, small and medium enterprises, cross-border payment mechanisms and trade finance solutions.

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) can also contribute to the expansion of fintech through opening markets to financial services imports, commitments to regulatory recognition or harmonisation and supporting general digital infrastructure.

E-commerce, the digital economy and trade

The digitalisation of the economy requires new ways of thinking about competition, intellectual property, taxation, industrial policy, privacy, cyber security, the labour market, immigration, skills, investment and of course, trade.

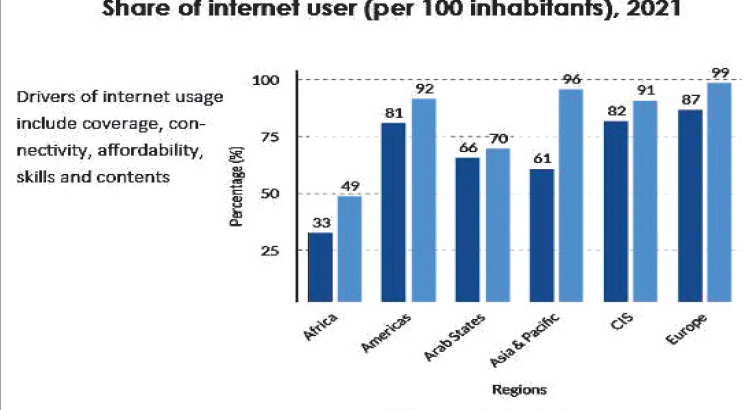

The wheels of international trade are powered by the Internet. From the smallest informal trade to a major supply agreement, contracts are trans-acted online whether via email, e-commerce store, or digital platform.

Any formal trade relies on the Internet for implementation—financing, documentation and logistics are all digitally driven and becoming more and more so.

Whether it is an emailed order, an online purchase, or merely the financial arrangements behind the transaction, the Internet will inevitably be used in conducting international trade.

Digitisation has contributed to a changing trade environment in many ways—facilitating multinational value chains, enabling the rise of the micro-multinational and giving us new tradeable goods and services.

It is also blurring the traditional boundaries between goods and services, blurring the boundaries between jurisdictions and bringing into question the way our legal and regulatory infrastructure operates at national, regional and global levels.

Digital permeates every aspect of trade from agriculture to clothing, from manufactured goods to business services.

Digital trade or e-commerce in trade agreements

Digital trade or e-commerce is increasingly becoming prominent in trade agreements. In 2021, there were about 105 trade agreements, including e-commerce or digital trade provisions. The provisions range from rendezvous clauses and best endeavours to e-commerce all the way to the comprehensive and justiciable provisions.

In 1998, World Trade Organisation (WTO)members adopted a declaration on e-commerce along with a Work Programme on Electronic Commerce and put in place a Moratorium on Customs Duties on Electronic Transmissions stating that WTO members would “continue their current practice of not imposing customs duties on electronic transmissions”.

The moratorium has been renewed every two years at the WTO Ministerial Conference. The last renewal took place in June 2022.

In 2019, 76 WTO members confirmed in a joint statement their intention to commence these negotiations. As of June 2022, there are 86 WTO members participating in these discussions.

In February 2020, the assembly of the Heads of State and Government of the African Union decided to include a Protocol on E-Commerce in the AfCFTA. The negotiation of this Protocol, now on digital trade, is under-way.

Taxing the digital economy

The development of the digital economy has brought many public policy and administrative challenges to governments worldwide. Among these is how an international taxation system that was designed for goods trade and physically present companies can work in a world where value crosses borders at lightning speed and co-location is completely unnecessary for a business-to-consumer relationship.

Two key issues in the tax debate are customs duties on electronic transmissions, including what is an electronic transmission) and corporate tax on companies that provide consumer services in a country, but have no physical presence there.

In January 2019, OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework (IF) on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting launched a process aimed at addressing some of the fundamental challenges arising from the digitalisation of the economy, including the allocation of taxing rights.

Subsequently, the IF has agreed on a two-pillar solution aimed at (1) a fairer distribution of profits and taxing rights among jurisdictions; and (2) introducing a global minimum corporate tax rate of at least 15 percent to protect the tax bases of respective countries and to curb international corporate tax competition.

As of June 2022, 141 jurisdictions have joined IF including more than half of all African countries.

Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, Egypt, Tanzania, Mauritius, Uganda, Cameroon, Ghana and Zimbabwe have either implemented or indicated that they plan to implement unilateral direct or indirect tax approaches in taxing the digital economy.

Africa’s digital economy has the potential to contribute $180 billion to

the broader economy by 2025, approximately 5.2 percent of the continent’s gross domestic product (GDP), and grow to $712 billion, about 8.5 percent of the continent’s GDP.—Tralac

One Comment